As Rev. Jesse Jackson used to say about the press covering his presidential bid, “If I walked on water, the headline would be ‘Jackson can’t swim.’” I often think of this quote when I see the way the political press covers polling data and election results. Once a narrative has been formed (in Jackson’s case, that his campaign was doomed to failure), confirmation bias takes over, reinforced by the increased risks of questioning what “everyone knows.” Confirmation bias by its nature is difficult to see, and even more difficult to question when those who should know better succumb to it – either because those narratives support their ideological perspectives, or because thinking about politics in those terms seems to be the only “serious” way to do so.

Pew’s “gold standard” validated voter study 1 of the 2022 midterms – replete with solid evidence that turnout is the key dynamic, voters rarely switch sides, and more – offers obvious exit ramps from some of the worst misconceptions about the midterms and elections generally. In this post, I will address three crucial ones: 1) the Biden 2024 doomcasting phenomenon and the faulty analysis that underlies it; 2) the ongoing failure to consider faith as a predictor of white voters’ partisanship; and 3) the blinders created by the conventional wisdom about education polarization.

In the Greek myth of Procrustes, an innkeeper delivers on his promise that his beds provided a perfect fit by either cutting off limbs that were too long or stretching those that were too short. Similarly, most political commentators and analysts – the people whose job it is to tell us what is true about elections – have struggled to make the surprising results of the 2022 midterms fit into the Procrustean bed of the usual frameworks and narratives they rely on.

Today’s post is the first of four related to the findings of the Pew study. In these posts, I’ll use the Pew report, and the media’s coverage of it, to show just where the chopping and stretching is happening, with the hope of finally getting us to a more accurate understanding of politics now.

This first post highlights the importance of confirmation bias and serves as an introduction to this series, by showing several recent examples of the media stretching and chopping Pew’s findings to fit into established narratives. The next two posts will dive deeper into:

Ecological fallacies. The foundational flaw with contemporary political analysis is the presumption that what is true generally in the United States is also true in whichever state or jurisdiction matters at the moment, as well as for whichever demographic groups are considered important at the moment.

Turns out, turnout matters. National polls can't tell us about the key element that we need to broaden our understanding about what decides elections today: how many people who support Democrats (or hate MAGA) will actually turn out to vote.

Credulous Forecasting

Consider this headline in the New York Times about the new Pew report:

Both the headline above, and the article accompanying it, make sense only if you ignore that in every midterm election, a greater proportion of those who voted for the outparty turn out than the proportion of those who voted for the president’s party. A better headline might have been, “Red Flag for GOP: Republicans make no gains with Biden voters even without Trump on the ballot,” or, “Red Flag for GOP: Despite gains elsewhere in the country, Republicans fall further behind in the Electoral College Battleground.”

Also missing is the context that presidents’ parties have rebounded in their House vote from the prior midterm in 10 of the 12 presidential reelection cycles since 1936.2 The only exceptions were in 1980, when Democrats continued to lose chunks in their then-enormous post-Watergate House majority as Reagan swept into office, and in 2004, because Republicans had not lost ground in the previous midterms, benefiting from post-9/11 glow. In the other 10 “normal” reelections, the president’s party rebounded by an average of 5 points – from a low of 1 point to a high of 8 points.3

While I absolutely don’t want to leave the impression that I believe that 2024 is in the bag, if you ask any presidential campaign manager after a difficult midterm whether they would rather have to win back voters who defected from them in the midterm, or turn out their supporters who skipped the midterm (most of whom usually skip midterms anyway), hands down they would pick the latter.

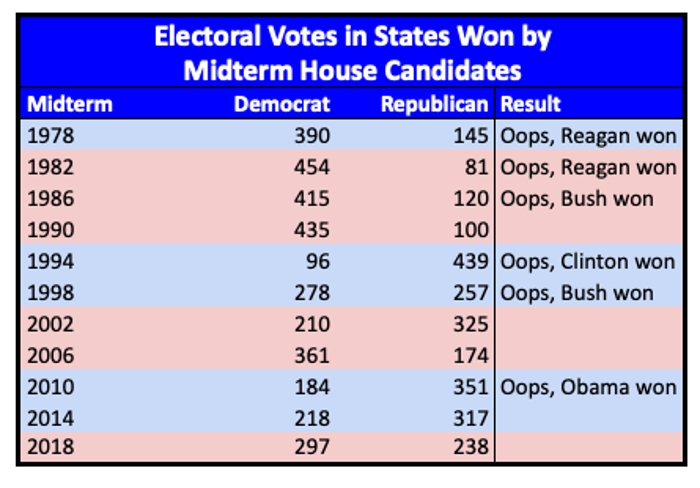

This is not an isolated example of ahistorical panic coming from the Times. In December 2022, the paper noted that Democrats lost the House vote in states that total 297 electoral votes. Because it was in the Times, and despite an obligatory CYA that it “doesn’t necessarily mean anything for 2024,” this point was picked up widely as ominous. But, consider: In 2010, Democrats lost the House vote in 36 states with 351 electoral votes, including nine Obama would win again two years later.4 Similarly, Reagan and Clinton were re-elected despite their party’s House candidates falling short of a majority of the electoral college in their first midterm, and Carter wasn't reelected even though House Democrats won enough electoral votes in 1978.5

The (Invisible) White Christianity Divide

As has been the case after every Pew release, the mainstream media completely ignored (or misunderstood) the significance of the study’s findings with respect to religion. Certainly, part of the media’s reticence derives from the politics of naming any faith in political stories - an almost certain backlash from those in that faith who protest (accurately) that what is being said about those with their faith is not true of them, or the principles of their faith, or the important role leaders in their faith played in progressive movements. On the other hand, I can’t imagine that the media gets much backlash from those without college degrees who feel that what is being said about them as a group is not true of them, others they know, or the historic role of non-college Americans. The problem is that the media’s reticence hides from view the enormous influence wielded in our politics today by faith leaders who weaponize their faith and exploit their tax advantages.

The White Christian Gap Is Consistently Greater than the White Education Gap

We have heard ad nauseam for the last six years that white voters are divided by whether they have a college degree or not. But consider that, together, white Protestants and white Catholics have favored Republicans by greater margins than white non-college voters have, while white non-Christians have favored Democrats by more than white college voters have.

The next graph illustrates that fact over the last four elections. Each set of bars pairs Pew’s results by white education (the first bar in the pair) with their results for white religion (the second bar in the pair). The bars above zero (blue), show Democrats’ margin with the Democratic-leaning groups (college/non-Christian6); the bars below zero (red) show Democrats’ deficit with the Republican-leaning groups (non-College/Christian). As you can see, in every cycle, white Protestants and Catholics were substantially more Republican than white voters without a degree, and other white voters were substantially more Democratic than white voters with a college degree.

White Christians Dominate the Republican Coalition

Thus, using the Pew data, we can see much sharper distinctions in the religious makeup of white voters in each party coalition than we are used to seeing. In the next chart, the three shades of red reflect, from the bottom, white Evangelicals, other white Protestants, and white Catholics. Blue reflects other white voters.7 As we can see, white Christians made up a huge proportion of the Republican coalition in each election, but they were a relatively small portion of the Democratic coalition.

The ridiculous irony of ignoring white Christian religion is that of all the electoral segments in the Pew report, white Christian religion is the only one for which there’s (1) a clearly understood set of values and political worldview associated with it, (2) a billion dollar communication industry that continuously reinforces its political preferences, and (3) a weekly reinforcement of that worldview for most of its adherents. Not to mention, megachurches play an essential role in setting the political tone beyond the devout.8

To the point about consistent reinforcement, the Pew study reports that in each of the last four cycles, nearly half of Republican voters attended church services at least once a month, and regular church-goers favored Republicans substantially, with a big jump coming in 2022.9 In other words, religion is one of the very few demographic groups that makes sense to look at, because its members have very common preferences and the group as a whole is politically organized.

So, instead of accepting that Republicans are "socially conservative" because they don't have a college degree, we should recognize the reality in front of our face, which is that they are "socially conservative" because they are overwhelmingly white Christians.

Say What?

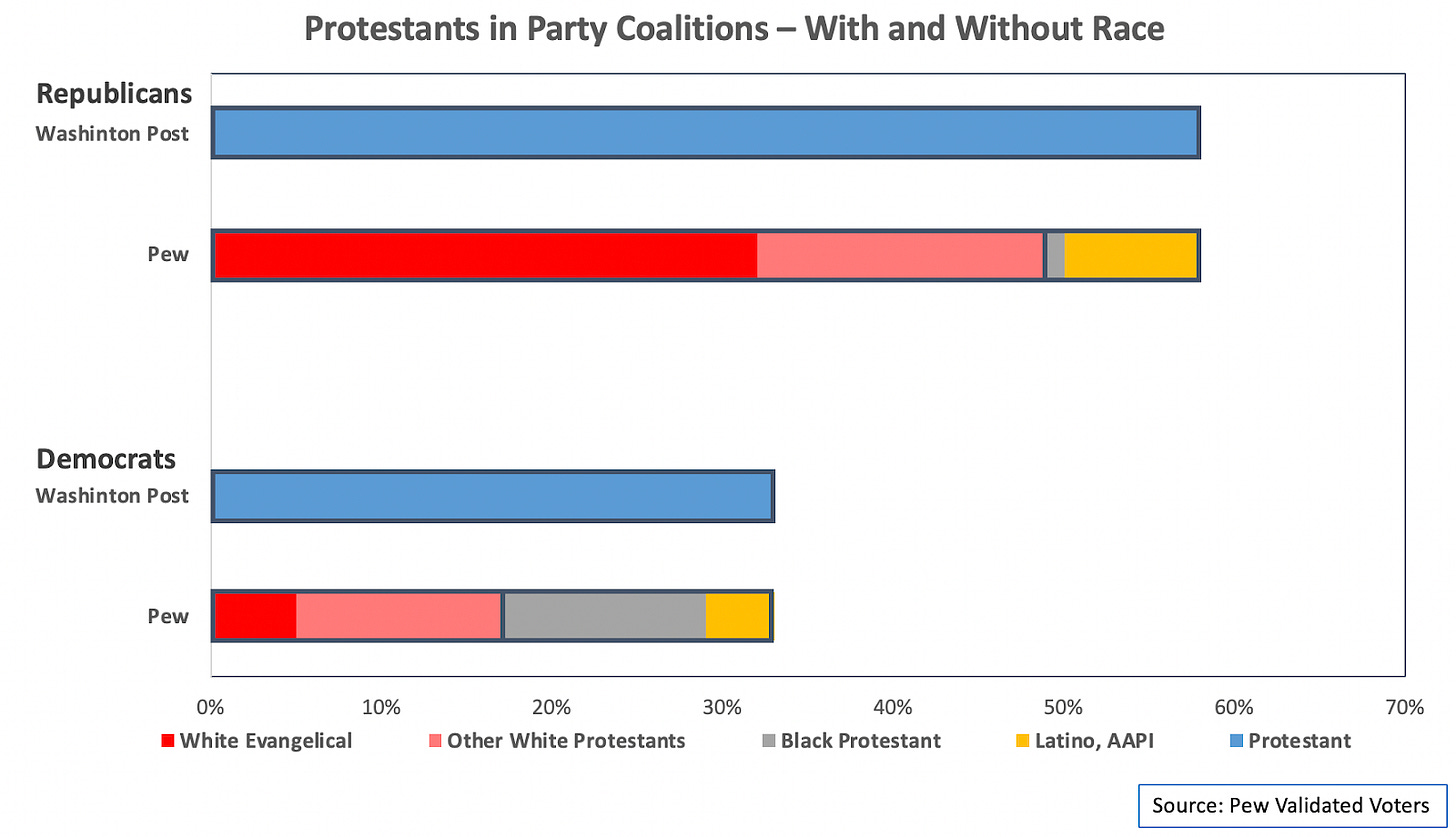

Incredibly, the only reporting I've seen on Pew’s findings about religion was in the Washington Post, which used the Pew data to “show” that the Democratic coalition is not much less religious than the Republican coalition. But to do that, they had to combine Black Protestants and Latino Catholics with white Evangelicals, other white Protestants, and white Catholics – as if anyone actually means “religious” literally when they say that religion divides us.

The next chart shows the proportion Protestants make up of each party’s voters - the top pair of bars Republicans, the bottom pair Democrats. The top bar in each reproduces the Post - all Protestants. The bottom bar in each pair divides Protestants by race, making clear that unless you consider white Evangelicals and Black Protestants to be the same thing, no meaningful debunking has happened.

The Shrinking Diploma Divide

In The Limits of Educational Essentialism, I argue that we pay far too much attention to “education polarization.” This section is more about showing how confirmation bias prevents those who believe in the paramount importance of education polarization from seeing evidence that complicates their narratives.

The so-called Diploma Divide between voters with and without a college degree is supposed to be the most important dividing line in American politics today, especially among white voters. Yet none of the news stories about the Pew findings mention this: Pew found that the gap between white college and white non-college voters has been shrinking.

Therefore, the following graph should come as a shock. It shows Democratic margins by white college attainment in the last four elections according to both Pew and Catalist (Pew = the solid lines in the graph, Catalist = dashed lines).10

Blue lines = Democrats’ margin with white college voters

Red lines = Democrats' margins with white non-college voters

Green lines = the size of the diploma divide (the white college margin minus the white non-college margin).

Although Catalist has consistently shown a smaller diploma divide than Pew, the trends in both series are the same - the green lines have been trending down since 2016.

Thus, contrary to the conventional wisdom about Democrats hemorrhaging white non-college voters, both Pew and Catalist show that in 2022, Democrats held steady with those voters while losing ground with white college voters.

Yet neither the Times nor the Post noted this in their coverage, instead casting attention on other trendy groups of voters. In fact, the Democrats’ declines in the groups these papers headlined were in line with (if not less than) the overall decline.

In the Times story, the 4 point Democratic decline with Latinos warranted the headline and mention in the article, while the 10-point Democratic decline with white college voters did not, despite the Latino drop being less than the national average and the white college drop being more than the national average.

This Washington Post story shifted the point of comparison from 2020 to 2018, without offering readers the critical context that the national swing between those two midterms was 10 points, or that the most important midterm driver (which party holds the White House) had reversed.

Also ….

I want to briefly draw attention to two shortcomings in the Pew report that reflect universal conventions in political data presentation. In these instances, confirmation bias is not at all a factor. Rather the errors are more unnoticed differences between what the data is said to represent and what the data actually represent.

Comparing Presidential Apples to Congressional Oranges

Pretty much every time you see how well Democrats (or Republicans) fared in a midterm, it is in comparison with how well their presidential candidate did in the previous election. But, it turns out that switching between those ballot levels can create apparent demographic trends that don’t actually hold up when consistently focusing on Congress.

Like many others, Pew uses presidential results in 2016 and 2020 and congressional results for 2018 and 2022. While the differences between Clinton and Biden’s margin and that of Democratic House candidates nationally seem de minimis – about 3 points – that did not reflect a consistent 3 point gap for every demographic group, with Clinton enjoying much larger margins than Biden did with voters of color, especially Latinos. (Biden’s advantage over House Democrats was spread more evenly.)

It’s relevant to this discussion because many of the 2022 to 2020 comparisons are meaningfully apples to oranges. For example, consider one of the most discussed trends of the last three years, Latinos abandoning the Democratic Party. Here is the data for Latino voters:

As you can see, the real story is that the Latino margin for House Democrats did not change between 2016 and 2020, and actually improved in 2022. But we think otherwise simply because of our habit to use the vote for president in presidential years, and the vote for Congress in midterm years. I can’t recall seeing a single story speculating on why Clinton did so much better with Latinos than House Democrats running with her down ballot, or noticing that Biden’s performance with Latinos was on par with House Democrats in 2016. In 2020, the Democratic presidential candidate “hemorrhaged” Latino votes; Democratic House candidates did not.

(Again, I don’t think this blunt categorical way of thinking about Latino voters makes sense; I am only arguing that if you do, the data doesn’t support the current narrative about it.)

Misunderstanding the Parties’ Demographic Composition

We’ve all seen those bars that show how different the Republican and Democratic coalitions are – there are plenty of them in the Pew Report. But none of them look at that question from the perspective that the elected representatives themselves have.

If you accept that looking at national aggregates for selected voter segments misses colossal regional variation, it won’t surprise you to find out that the same is true for congressional districts. For any given voting segment, their Democratic margin will differ if they are in a district safely represented by a Democrat or a Republican, or if the district is highly competitive. For example, according to Catalist, Latinos in Democratic districts favored the incumbent Democrat by about 46 points. But in Republican districts, Latinos favored the Democratic challenger by only 11 points, and in competitive districts, Latinos favored the Democrat by 28 points.

With that in mind, this chart gives us much closer to a realistic perspective of the current composition of Democratic and Republican coalitions, from the perspective of the actual Democrats and Republicans those coalitions elected. Again, reports like Pew’s only give us the leftmost bars in both panels, the results from all the congressional districts combined. The bars second and third from the left show the composition of voters in congressional districts electing Democrats and Republicans, respectively.

Why is this important?

If you are a Democratic or a Republican House member, you know that the Democrats/Republicans in your district are more liberal/conservative than Democrats/Republicans are nationally. Thus, when political commentators ridicule as irrational Democratic politicians for being to the left of their own median voters, they again make a substantial mistake of assuming that what is true for the nation, is true for them.

Of course, most representatives are responding to the voters in their districts (not all Democratic districts), so even this is offered as a better approximation to illustrate the directional misrepresentation. And, given majority-minority districts, it becomes more complicated still for Democrats.

Footnotes:

The Pew validated voter studies of the last four elections provide one of the the most rigorous and comprehensive views of the electorate, combining high-quality polling, panels which can isolate whether individual voters are changing their allegiances, validation on the voter file, and inclusion of eligible voters who did not cast ballots.

I began in 1936 because that was the first reelection with a stable number of members in the House and minimal third party competition.

Those states were Colorado, Florida, Michigan, Nevada, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Wisconsin.

Christian combines white Evangelical, other white Protestant and white Catholic.

Jews, Atheists, Agnostics, and nothing in particular.

See, for example, Katherine Stewart, The Power Worshipers and Ann Nelson, The Shadow Network, Butler, Anthea - White Evangelical Racism: The Politics of Morality in America, Ziegler, Mary - Dollars for Life: The Anti-Abortion Movement and the Fall of the Republican Establishment; Blum, Rachel - How the Tea Party Captured the GOP; Balmer, Randall - Bad Faith: Race and the Rise of the Religious Right; Jones, Robert - The End of White Christian America and White Too Long; Whitehead, Andrew and Perry, Samuel - Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States; Parker, Christopher and Barreto, Matt - Change They Can’t Believe in: The Tea Party and Reactionary Politics in America; Skocpol, Theda and WIlliamson, Vanessa - The Tea Party and the Making of Republican Conservatism; Brody, David: The Teavangelicals: The Inside Story of the Evangelical and the Tea Party and Taking Back America; Schlozman, Kay Lehman - The Unheavenly Chorus: Unequal Political Voice and the Broken Promise of American Democracy; Howe, Ben - The Immoral Majority: Why Evangelicals Chose Political Power Over Christian Values; Kruse, Kevin - One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America; Hollinger, David - Christianity’s American Fate: How Religion Became More Conservative and Society Became More Secular; Gorski, Phillip and Perry, Samuel - The Flag and the Cross: White Christian Nationalism and the Threat to American Democracy

Note - Because Pew does not break their data down for partisan choice AND race, that ballpark is computed by backing out Black Protestants for which there is separate data.

Note - both ANES and CES show greater white education gaps. But, again, the point here is more about showing how conventional wisdom resists evidence that undermines the accepted education polarization narrative rather than establishing an accurate point estimate for it.

I love this! I’ve long viewed self-righteous indignation to be the heroin of the evangelicals. It’s hard to turn away from the elixir of joy and anger no matter how many wacko-do things you have to integrate into your belief system to stay there.

I kinda wonder whether media refuses to acknowledge (White) religion as the driver of their polarization less due to a commitment to the educational gap and more due to their desperate grasping for White Christian viewers.