Don't Panic About Biden's Approval Ratings

Do panic that voters will forget that their freedoms and well-being are on the ballot again.

In the wake of President Biden’s announcement that he will seek re-election, there have been many stories assessing his chances of winning. Most if not all of these stories point to Biden’s low approval ratings as a danger sign, as they are well below the ratings of presidents in previous decades, and of nearly all presidents since the beginning of approval polling in the late 1930’s.1

In this post, I will explain why approval ratings are an illusory measure of a modern president’s electoral chances. While voters may be responding to the same approval questions today that they have for the last 90 years, presidential approval simply doesn’t have the same electoral significance today that it has in decades past. A president in the 20th century was very likely to enjoy broad majority support for all or nearly all of their term in office. But, as you will see, low and stable approval ratings have become the defining features of presidential politics since W. Bush’s 9/11 bump faded in 2003.

Today, voters are far less likely to approve of presidents they didn’t vote for, regardless of what that president actually does in office. And a president who doesn’t have a voter’s “approval” may nonetheless earn their vote. Voters can now be thought to fall into three buckets:

Partisans. Nearly half of Americans positively support one or the other party (these voters define the lower bounds of presidential approval);2

Affective Partisans. About a third of Americans absolutely reject the other party, but are not that enthusiastic or satisfied with the party they vote for (these voters define the upper bounds for approval);3 and

Partisan Bystanders. About one seventh of Americans either lack strong feelings about both parties or are strongly hostile to both parties.

This taxonomy is important, because by November 2024, the votes of those in the second two buckets will be determined by their hostility towards or fear of Biden’s opponent (as they were in 2020 and 2022), not a conversion to active approval of Biden or Democrats. In the meantime, their answers to survey questions about presidential approval will be ephemeral, amounting to not much more than statistical noise.

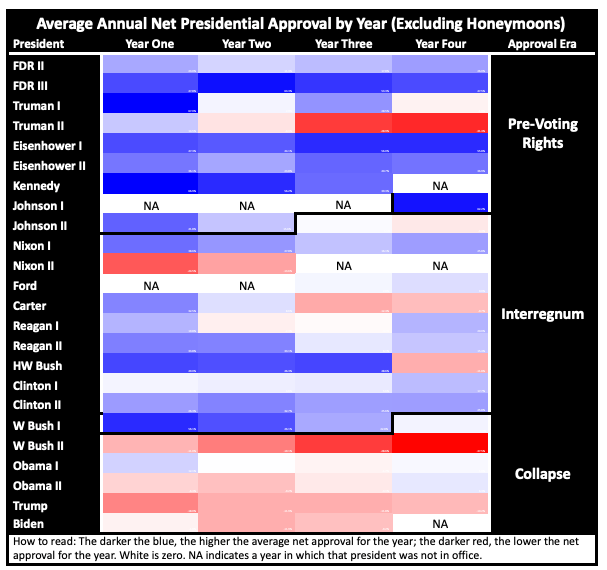

Average net presidential approval4 has changed in an almost stepwise fashion in three phases:

Pre-Voting Rights Era from 1937 until the enactment of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, during which presidential net approval was very rarely negative;

Interregnum from the enactment of VRA until late 2003, when support for the Iraq war began to evaporate5; and

Collapse from then to the present. The collapse in the “Collapse” Era has been twofold: Not only did net approval decline in a stepwise fashion, the range for net approval shrank dramatically.

This chart shows annual average presidential approval since 1937, with the dotted horizontal lines indicating the average for each era. Note that this excludes the honeymoon period, which would have made average differences between this period and earlier ones even greater.6

These stepwise drops reflect voters’ growing alienation from, and lack of confidence in, our national governing institutions much more than they are assessments of individual presidents’ performance. This is especially true in the period we are in now, in which the range in net approval (from peaks to valleys) is far smaller than in the previous eras. Today, a voter’s response to a presidential approval question is much more a reflection of how they feel the system and the general direction the country is going in, than it is to the particular president or current events.

I’m not making these arguments to forecast results in 2024 – on the contrary, I am making these arguments in the hope that we will stop holding a microscope over each poll that shows Biden’s approval moving up or down within the bounds of presidential approval we have seen for the past 2 decades. At this point, if media polls want to better serve the public, they would scrap the approval question, as well as the trial heat, and instead, for example, ask respondents to rate the possibility that they will vote for Biden and for Trump (two separate questions). This is one strategy that actual campaigns, as well as others with resources and high stakes in the outcome, use to get better insight into the race.

As I’ve written elsewhere, the ascendance of the MAGA movement, and especially its expression in governing (the Trump presidency, Dobbs, etc) has, since 2017, radically changed electoral politics. While far more people are voting on both sides, the increment of new voters who reject MAGA is far greater than the one that supports it. Yet, the obsession with Biden’s approval numbers creates the illusion that his path to re-election depends on making him and his administration more popular, and not on ensuring the roughly 90 million people who have voted against MAGA in the last three elections do so again in 2024.

Ruy Teixera’s Substack post “Five Reasons Why Biden Might Lose in 2024 Even if His Opponent is Donald Trump” inadvertently illustrates the only real reason that Biden might lose the election: a political class so obsessed with seeming savvy and “even-handed” that it relentlessly ignores the catastrophic consequences of a second Trump Administration. (See, for example, Hillary’s emails.) While it may be impossible to prevent that entirely, I hope this post will make it clear why those who concern-troll about Biden’s approval ratings are not serious political thinkers, and why those who continue to represent what is now a decade-long trend of negative numbers as reflections on particular politicians – rather than as indicative of broad and intense dissatisfaction with our governing institutions and political parties – are engaged in what John Jost has diagnosed as system justification.

Finally, an important reminder. All survey data (as well as election results) before the late 1960’s are severely flawed as reflections of what “Americans” thought or chose because, of course, until at least the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, they did not fully reflect the attitudes of Black Americans. And there is some evidence that this remained true for the Gallup Poll into the 2010’s.

Presidential Net Approval

This first table shows the averages for approval and for the ranges7 for each period.

It’s also interesting to look at approval ratings in terms of their relationship to the margins8 presidents were elected by, something that is rarely if ever done, which the following graph does. (The gaps in the graph are for the years that vice presidents became president, for which there is no comparable benchmark.)

This next table shows that not only were presidents much more likely to be above water in the first two periods, they were also able to sustain approval ratings well above the margins they were elected by. On the other hand, presidents in the current era have been an average of 8 points underwater in net approval and an average of 11 points behind their election margins. In other words, presidents in the first two eras routinely enjoyed support from significantly larger majorities of Americans than had voted for them in the first place. Today, presidents usually govern with the approval of fewer than half the population, which is obviously even less than the percentage of the electorate that voted for them. And they stand very little chance of gaining the approval of the people who didn't vote for them.

Now, let’s get under those broad aggregates to get a more granular idea of what’s been happening. With the exception of Truman’s disastrous last two years in office and Watergate, the following chart vividly shows how demarcated these periods have been, with blue representing higher approval, and red representing lower (“NA” indicates that that president was not in office that year; for example, Ford did not take office until the third year of Nixon’s second term.)

Now, let’s look at month to month variation. The measures we’ll use here are the number of months the president’s average net approval is negative, and the number of months it is below their election margin. How to read: Net approval was negative in only 13 percent of the 220 months in the Pre-Voting Rights period, compared to 77 percent of the 202 months in the current period. (Note that there are fewer months in the early years because polls were not available for every month.)

In the Pre-Voting Rights Era, presidents were underwater in about 1 out of 8 months they served; in the Collapse Era, it was nearly the reverse - they were underwater in 6 out of 8 months they served. And where Pre-Voting Rights Era presidents fell below the share of the vote that elected them, Collapse Era presidents were so just shy of 90 percent of the time.

Here I want to come back to the idea that not only has net average presidential approval been declining, the approval measure itself cannot reasonably be said to be measuring the same thing today as in the past. If we flipped a coin 500 times and only got heads 50 times, we could either believe we were extraordinarily unlucky, or that we were flipping a weighted coin. Fortunately, there is a mathematical way to understand the likelihood of such events that we can use to inform our judgment: cumulative binomial distribution.

Now, let’s think of the 385 months in the Interregnum Era as “coin” flips. In the previous era, Pre-Voting Rights, the “coin” came up “tails” (negative) 13 percent of the time. If we were using the same “coin”, the odds of it coming up “tails” at least 87 times in these 385 months (23 percent) is less than 1/100,000 of a percent.9 And, of course, the drop down from Interregnum to Collapse is even more improbable. (You can try it yourself here.)

Now, let’s look at some of the other ways presidential approval ratings have changed from era to era.

Presidential Approval Between Tight Bounds

Not only has average net average monthly presidential approval been underwater in the Collapse Era, it has remained in a historically unprecedented narrow range. The graph shows the highest and lowest monthly net approval for each year beginning in 1953.10 By the fourth quarter of 2009, the pattern that has held since was set. Since then the average range in net approval has been just 9 points. This compares with an average of 24 points for the previous six decades. Indeed, the lowest average for any previous 13 year stretch was more than twice that (20 points), and it was in the period immediately before, from 1996 to 2009.

The last two years of the Bush Administration were the last time that partisans of either party were ready to tell pollsters that they disapproved of the job their party’s president was doing.

Moreover, the asymmetric nature of media ecosystems means that, all things being equal, the approval ceiling and floor is lower for Democratic presidents than Republican presidents because the mainstream media is much more likely to report something negative regarding a Democratic president than FOX is to report something positive that a Democratic president has done, but FOX criticizes Democratic presidents at least as often as the mainstream media criticizes Republican leaders.

What that means for approval ratings is that respondents, who understandably rely on journalists and media to inform them of policy developments and current events, partially reflect the aggregate sum of their respective media coverage. For Republican leaders, this is positive for FOX viewers, and negative for mainstream media consumers. However, for Democratic presidents, FOX viewers see only negative coverage, where the mainstream media audience gets a mixture of positive and negative. It is, for example, impossible to imagine that among Democrats, Joe Biden would have a positive approval rating (let alone an overwhelmingly positive approval rating) had he tried to overthrow a presidential election.

To be clear, I am not advocating that the mainstream media emulate the partisan loyalty modeled by right-wing media and only offer positive coverage of Democratic presidents as a sort of counterbalance. A healthy democracy requires a robust adversarial press. The MSM mission to provide balanced coverage (even if it frequently fails, often catastrophically), is essential. The alternative – a mirror image of Fox – would be much, much worse.

It is also worth noting the role that organized civic institutions play in presidential approval ratings. Compared to the earlier periods, most Americans hear much less from trusted civic institutions now than they did then. The overwhelming support Republicans receive from white Evangelicals is very much a product of the saturation of what they hear in the church communities and through Christian broadcasting. We often hear pundits puzzle over why Biden and Democrats get less acknowledgement for what they have done. That is very much a result of the breakdown of the New Deal grassroots order, in which much higher union density and robust local Democratic parties meant that the Democrats’ commitment to working class voters was heard in the same trusted surround sound that Republicans’ commitment to white Christian nationalism is heard today.

In this connection, it’s worth looking at net approval as a function of economic order and party. The next table shows that during the New Deal Order, net approval was substantially higher than it’s been for presidents during the neoliberal order. Moreover, it’s worth noting that during the New Deal Order, net approval for Democrats was substantially higher than it was for Republicans, while in the Neoliberal order there has been no partisan difference. The difference by partisanship during the New Deal Order and the lack of difference in the neoliberal order likely reflects the differences in the ways in which working class voters received political information from those they trusted.

Honeymoons Are Getting Shorter

So far, I have excluded the “honeymoon” periods from the analysis because they have been getting shorter and shallower in the same step down fashion I described, meaning that had I included them, the differences in average net approval between the eras would have been even greater. Here, I just show that even within honeymoon periods, the pattern holds.11 Before the current era, the only president underwater in December of their election year was Nixon, due to Watergate. Obama in 2009 is the only one of the five presidencies in this era to finish above water (barely, at +6.1 percent, already a decline from his election margin).

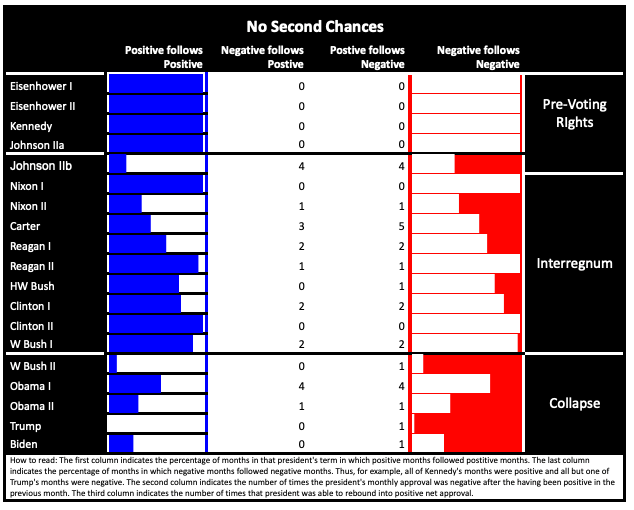

Presidents Don’t Get Second Chances

Another way in which the three eras are different is the extent to which the first negative net approval can be turned around. In the Pre-Civil Rights Era, beginning with Eisenhower through most of 1966, there were no negative months at all.12 In the Interregnum, most presidents had more consecutive positive than negative months (the first and fourth columns), and almost every president who had a negative month (except for HW Bush) turned it around at least once before the end of their term (the middle two columns). But in the current era, Obama is the only one to have recovered from a negative rating (barely), and his first term is the only one in which there were more consecutive positive months than negative months. W Bush II, Trump and Biden, have not come close to recovering once their net approval went negative.

System Disapproval Is Expressed as Presidential Disapproval

In this section, I want to begin to unpack how we should understand the reasons for, and meaning of, those stepwise declines in presidential approval. Of necessity since this is a Substack post and not a book, this will be schematic; there’s obviously more to it.

Each stepwise decline followed a major shock to the voters’ confidence in the nation’s institutions and leadership, as well as challenges to the prior relations of social power. The dismantling of Jim Crow, the bitter divide over the war in Vietnam, sudden and extensive campus and urban unrest, Watergate, and stagflation were among the most important shocks undermining confidence voters had in the nation’s governing institutions in the Pre-Voting Rights Era. And it was reinforced by the anti-government rhetoric that was spread and reinforced by Presidents Reagan (“Government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem”) and Clinton (“The Era of Big Government is Over”). The terrorist attack on 9/11, the folly of the invasion of Iraq, the Great Recession, and the racist backlash to Barack Obama’s election were among the most important shocks further undermining confidence in governing institutions. Furthermore, as Suzanne Mettler observes, the Obama Administration purposefully pursued progressive policies through what she calls the “submerged state” (for example, offering tax credits instead of direct benefits provided through a visible public program, like Medicare). Such policies “obscure the role of the government and exaggerate that of the market, leaving citizens unaware of how power operates, unable to form meaningful opinions, and incapable, therefore, of voicing their views accordingly.”13

With that in mind, consider the fact that it seems like not a week goes by without a report on another poll or study about voters’ declining confidence in government generally, or in particular institutions. The American National Election Services (ANES) has been tracking two such indices through all three periods. When it comes to voters' trust in government and belief in citizens’ political efficacy, we see essentially the same pattern of stepwise decline from period to period that we see with presidential approval.

A recent Pew report does not provide the same longitudinal window. But it does show what, if reported about another country, would easily be seen as a rapidly accelerating decline in citizens’ confidence in and support for its institutions and leaders. Clockwise from the top left: a majority of Americans believe that America cannot solve many of its important problems; three-quarters believe that the US economic system is unfair to most Americans; two-thirds disapprove of the job Biden as well as Democratic and Republican congressional leaders are doing; and 80 percent say they are dissatisfied with the way things are going in the United States.

According to a Brookings survey, even as recently as 2010, the country was divided evenly between those who thought that the government needed to change “not much at all” or needed “only some reform” and those who thought that the government “needs major reform.” Today, it’s a 20 point spread in favor of needing major reform.

Procrustean Punditry and Misunderstanding the Moment

In the Greek myth of Procrustes, an innkeeper achieved a “perfect fit” for travelers in his beds by either slicing off limbs that were too long or stretching those that were too short. In the same manner, pundits prefer slicing off the mounting evidence that the electoral dynamics have changed radically in the last decade. Moreover, in the real world, not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted. But our pundits operate on the presumption that only those things that can be counted easily, and especially those things that have been counted for a long time, can possibly count. It’s a bias for what’s obvious and narrowly accurate over what’s complex and comprehensively true.

We hear a lot about how "polarization" makes American politics less functional, and the idea that Americans have largely chosen their partisan "teams," and that their behavior can be understand in terms of the same tribal impulses expressed in sports rivalries (Yankees vs Red Sox), or clan rivalries (Capulets and Montagues). The problem with doing that is it ignores the evidence from polling. In most surveys, pollsters ask whether the respondent considers themselves a Democrat or a Republican. If the respondent doesn’t choose either, she is asked whether she leans to one party or the other. Pollsters have been doing this for quite a while since it was recognized that those who, in the second question, say they lean towards one party or the other are about as likely to vote for candidates of that party as those who identify with that party in the first question. Generally only about two-thirds of respondents identify with a party on the first question, and another fourth choose sides in the second question. The ANES survey also asks those who chose a party on the first question whether they are a strong or weak partisan. Of the two thirds who identified with a party on the first question, a third say they are a weak partisan.

In other words, we are a country in which nearly all of us have chosen sides, but only 40 percent strongly identify with the side we’ve chosen! To go back to those archetypal tribal rivalries, it would be as if only half the screaming fans in Fenway Park were willing to say they were Sox fans.

We are a nation in which 85 percent of us passionately hope one or the other team loses, but half of us would be fine if neither won.

Given what we now know about presidential approval ratings in the current period, as silly as it is to obsess over Biden’s approval ratings in aggregates like FiveThirtyEight’s, think about how many articles you’ve read that take movement among a particular demographic group in a single survey as a significant signal. Remember that even if that single survey has 2000 interviews, it will be inevitable that (1) at least one subgroup will show statistically significant movement, and that (2) it would be almost certain that if the same pollster conducted the same poll on the same day, using the same methodology five times, those surveys would not confirm the movement.

Conclusion

Over the last 50 years, the United States went from being one of the most equal countries in the Western World in terms of wealth and income to nearly the most unequal, with real median household income barely increasing over the last fifty years. It has been one of the world's greatest impediments to more rapid transition away from fossil fuels; is the only major nation in the Western world where life expectancy was decreasing for sizable segments of its population even before COVID; and has become stingier in its provision of basic needs even as it has regularly reduced taxes on its most affluent citizens by trillions of dollars and protected the profits of the military-industrial complex. And no “Western democracy” maintains a racialized carceral state as massive as ours, or permits so much proliferation of firearms with such indifference to its consequences.

Yet every time a new survey is released showing that Americans’ confidence in the nation’s institutions or in “democracy” has reached a new low, “serious people” wring their hands and wonder what can be done to correct our perceptions. And they despair of the corrosive effects of social media rather than entertain the possibility Americans are simply paying attention. More corrosive to our social fabric than the lies spread on social media are the truths that our leaders, and the plutocrats who support them, operate above the law, and that the “greatest economy in the world” enriches only those wealthy and powerful few – leaving more and more Americans with diminished prospects for themselves and their children and succumbing to deaths of despair.

As we head into another election when fascism is on the ballot, we cannot allow ourselves to be distracted by those who brandish low approval ratings to turn the focus onto Biden, and who act as if insidery campaign messaging and tactics are the sole determiners of whether Democrats win or lose. This same crew told us for two years straight that Democrats would be routed in the midterms if they didn’t find the right message and move to the center. They sternly told us to downplay the January 6th hearings because voters would see them as too partisan and an effort to distract from the “real” bread and butter issues they cared about. These pundits were sure that every attempt to hold Trump and his criminal co-conspirators criminally accountable would backfire with voters (even though that accountability is literally the Justice Department’s responsibility). And yet, as has been the case for the last two elections, outside Red America voters rejected MAGA candidates in nearly every state and district where MAGA was a salient threat. Had the media not been so convinced by its own savviness that retaining control of the House would be impossible, today, it’s likely that none of us would be thinking about the debt limit.

That is the earliest Gallup data available through the Roper Center. I use Roper Center data through 2016, and then the trends line data set made available by FiveThirtyEight. To be clear, none of the pieces I refer to go back all the way to the 1930’s. I do, to make it very clear what contemporary approval ratings actually mean by the contrast.

These are the voters who answer the question “Which party do you identify with?” as either Democrats or Republicans.

They are the voters who say they are neither Democrats nor Republicans but strongly disapprove of one party or the other, OR they say they are weak partisans if there is a follow up to the first partisan identification question.

Net approval = approve minus disapprove. Average net approval = the average net approval for a unit of time - either month (in which case it’s the average of all the polls taken that month), year (in which case it’s the average of the average for each of the twelve months), or era (in which case it’s the average of the monthly averages in the era).

The interregnum period could actually be divided into two sub-periods, during and after the Cold War, but that’s beyond the scope of this post.

I’ve defined the honeymoon period as the first six months after the presidential election. Omitting this better clarifies the changes over time.

To avoid confusion - that is the average of annual highs and lows in the period, not the highest and lowest across years in the period.

The margin is the percentage the president won by of the two party vote. President Biden’s margin was 45.5 points - the difference between his 52.29 percent of the two party vote and Trump’s 47.7. Shares, or margins of the two party vote are conventionally used for longitudinal comparisons. When presidential margins are compared to net approval I adjust the net approval to remove undecided.

Even some who are mathematically inclined may find this probability smaller than their intuition. The reason is the law of large numbers. In this kind of example, it should be easy to see that it is much, much more likely that you could flip heads three out of four times than it is that you would flip heads 3 million out of 4 million attempts.

There were not enough monthly polls before that.

Not shown in this chart - FDR and HST because there weren’t frequent enough polls, and Johnson I and Ford because they had assumed the office.

Polling during the Roosevelt and Truman administrations were too infrequent to include in this month to month analysis.

Mettler, Suzanne. The Submerged State (Chicago Studies in American Politics) . University of Chicago Press. Kindle Edition.

I've found myself drawn to checking out more fiction audiobooks from the local library lately.

There's a distinct need to turn off the noise and tune out the negativity and just do something productive while I listen (yard work, household projects, postcards to voters).

I realize I've spent far too much emotional and intellectual energy staying apprised of "the situation" and instead of filling myself with existential dread on a near constant basis I need to focus on the things I can control, volunteer and donate where I can to push forward the democratic cause. Trump, DeSantis, and the GOP are going to keep saying and doing whatever fascist thing, and it does me no good to be angry or afraid.

It's best to stay determined and energized by things I love, and to do the few things I CAN ACTUALLY DO to take a stand against anti-democratic forces in this country.

It seems the constant fire hose of doubt and drama and the media's insistence that the right "is also a viable and legitimate political party" really only serves to dispirit us from hoping and trying for a better future.

Great read, as usual!