I hope you all had a good Thanksgiving break and are ready for the year ahead. Over the weekend, I reread what I posted two years ago, after Democrats’ disastrous odd-year election results. I’ll begin there in this post because what I wrote then remains relevant today – which is that political discourse remains committed to sportscasting the future of American democracy as a contest between two political parties, in which we are spectators who can only root for Democrats to save us. And so, as was the case two years ago, we debate whether to fire the coach, argue over which plays he should call, and position ourselves to have been right all along if the Democrats lose.

Then, I’ll tackle two questions that came up in my recent appearance on The Ezra Klein Show – and that probably came up at Thanksgiving dinner for many of you. There was a lot of good pre-Thanksgiving advice for handling Trump uncles, but not enough for handling catastrophizing cousins, who might be crying:

We’re doomed! Biden is too old! The truth is, people have been deeply dissatisfied with the direction of the country for decades, and believe that our institutions and political system need major reforms. Biden’s age is no doubt a liability, but it’s pure fantasy to imagine that we can guarantee Democratic victories by replacing Joe Biden on the ticket. The same folks who are telling us that Biden is too old now would be telling us that some other problem with a different candidate is the reason Democrats are doomed. There are no magic wands in politics.

We’re doomed! Voters don’t realize how good the economy is. The problem is that most Americans’ experience of the economy – the precarity that most working people face in terms of inflation, unemployment, workplace insecurity, and the impossibility of realizing the American dream – can’t be captured by the zombie economic indicators that the already-prosperous convince themselves still describe how the other 9/10ths live.

Two years ago at Thanksgiving 2021, just three weeks after Democrats had done so badly in Virginia, I wrote:

This Thanksgiving, there was little doubt that we had much to be thankful for in the last year, but we were nonetheless gloomy that we will have little to be thankful for at this time next year. … Before the Virginia governor’s race, my deep alarms about the midterms were seen as too skeptical of the rewards that would come from enacting an ambitious agenda and returning the country to “normal.” Now, my observation that Democrats can overcome the usual midterm dynamics by making known what is true - that MAGA remains just as much of a threat as ever - also risks being dismissed, but this time by an unwarranted pessimism.

Now, as then, we can’t let needless panic or heedless optimism distract us from the real task ahead: Making sure voters continue to clearly understand that elections are no longer personality contests, but biennial referenda on whether we will have a fascist future.

Is Joe Biden’s Age Really the Problem?

For nearly the entirety of the 21st Century, Americans have felt that the country was on the wrong track. And since the Great Recession in 2008, they have felt that by nearly 3-1 margins.

With that in mind, is it really surprising that…

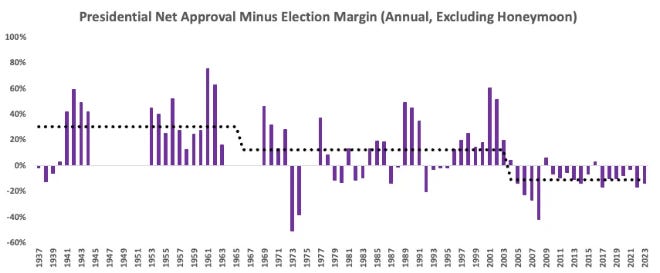

Americans No Longer Like their Presidents

It’s worth taking a step back to appreciate just how unique Biden isn’t when it comes to unpopularity. It’s time we ask not what Biden’s approval ratings tell us about him, but what Biden’s approval ratings tell us about America.

As I’ve explained in more depth already, low presidential approval ratings are now the norm in the United States. The last three presidents – including one who was twenty years younger and another thirty years younger than Biden at the same point in their presidencies – spent all, or nearly all, of their terms in office underwater. In this period, in only one instance has a president rebounded fully to net positive after passing into negative territory.

Firing Chefs When the Problem Is the Restaurant

Approval numbers are just as bad or worse for Congress. The next chart shows that every one of the last five U.S. elections has seen at least one branch of government change parties. This has also happened in eight of the last nine elections1 – as many as in the 23 elections before that. It’s a dramatic shift that indicates a perpetually dissatisfied public:

Moreover, since at least The Great Recession, majorities have favored major government reform – yet in none of the elections since then has either party made major government reform an issue, unless you count Trump’s promises to drain the swamp.

The nation’s most important institutions, from Congress to the Supreme Court to the media, have also seen sharply declining approval. Many of our leaders see these statistics and ask how we can restore voters’ confidence in our institutions – instead of asking how we can make these institutions more worthy of voters’ confidence. When mainstream discourse refuses to take the latter question seriously, it preempts any serious discussion of our need to find a better way to live together and flourish in the 21st Century.

Actually, Pretty Much No One Likes Their Leaders Anymore

Such broad-based dissatisfaction is not limited to the United States, especially in the wake of the 2008 crash. The following chart shows that of the seven countries regularly surveyed by Morning Consult, only the Swiss have positive feelings about their leader and their country’s direction. You’ll notice that all of the other leaders are younger than Biden, and that they come from left, center, and right parties. And, interestingly, you’ll see that Biden is less unpopular than the other world leaders with respect to how pessimistic people already are about the direction of their country. In other words, more people approve of Biden while also thinking their country is going in the wrong direction than is the case for other world leaders. (That difference is expressed by the horizontal black bars, which subtract country direction approval from presidential approval.)

There Are No Magic Wands

On November 27th, I don’t know whether Democrats have a better chance next year if Joe Biden is their nominee or if he’s not – and neither does anyone else. Yet many treat “Biden or not” as the most important question in politics right now. What strikes me as important, though, is that none of them (1) have anything enlightening to say about Biden’s shortcomings other than that he is old, (2) offer a credible path to a different nominee, or (3) attempt to calculate the downside risks of running a less-tested, non-incumbent candidate instead of Biden. Remember that Hubert Humphrey, the only remotely recent candidate to attempt to succeed a president not seeking re-election, lost in an election that was a watershed; Democrats had won seven of the previous nine elections, but went on to lose five of the next six by mostly lopsided margins.

How We Mismeasure Prosperity

Why aren’t Biden and Democrats getting credit for what to some looks like an objectively good economy? For starters, we need to take a hard look at how we've come to define a “good economy.”

Zombie Indicators

As I said on “The Ezra Klein Show,” the metrics that have long been used by political analysts to assess the economy – particularly GDP – are broken. While those measures reflected most people’s experience when rising tides lifted most boats, now those tides lift only yachts. As such, traditional economic metrics are unmoored from most people’s experience. This point was picked up widely on social media and then conclusively demonstrated in this New York Times guest essay by Karen Petrou with respect to GDP.2

It’s not just about the unequal shares of the pies. As Mariana Mazzucato powerfully argues in The Value of Everything, much of what is counted in GDP (such as finance or economic rents) is of no, or negative, value to most Americans.3 She astutely points out that modern economies reward activities that extract value rather than create it, which leads to obvious injustices.

And it’s not just GDP; many of our other favorite economic heuristics are broken as well. Consider “unemployment.” Today, those being counted as “employed” can have less confidence in the duration and terms of that employment as they have had in the past.

Which brings us to…

Precarity

None of those standard metrics even attempt to measure the level of precarity Americans experience when trying to make ends meet, even in a time of statistically low unemployment. It’s also well known that confidence never rebounds immediately to the latest quarter’s “good news.” Traumas leave scars.

Below is a non-exhaustive list of factors that make Americans feel their economic situation is more precarious than the traditional indicators would have you believe. Most of these factors either receive too little public attention or too few visible and credible efforts from politicians to address the problem.

- Inflation

Unlike nearly every other “issue” which can be ignored by most Americans in their daily lives, inflation insists on voters’ attention – and not just at the gas pump. The financially stressed have a kind of mental overhead that those who are not financially stressed don’t: constant mental checkbook balancing, constant recognition that buying this means not having that, and constant doubts about your ability to provide for those you care about most. Rising prices compound those daily recalculations of how to make it through the month, because you cannot even be certain of the prices for your immediate necessities.

Thus, while economists celebrate reports of inflation cooling as welcome news, those with little margin for financial error do not. Less inflation doesn’t mean price stability, only that prices are not rising as quickly. In other words, financially stressed Americans' economic positions have not become any less precarious; for now, they are just becoming more precarious more slowly.

Moreover, especially after an era of wage stagnation, it is human nature to see wage increases as having been hard-earned. Even charts like the one above miss an important but subtle point. The enthusiasm working people have for the current 1.2 point differential between wage growth and inflation depends greatly on whether they thought their paychecks were sufficient to begin with. Charts like these visually imply that 2017 wage levels were good enough. If they weren’t in 2017, when inflation was not eroding their paychecks, there’s no reason to assume that working people are overjoyed now.

Obviously, inflation does not always lead to authoritarianism. But when inflation is a feature of the political environment, it often compounds the weakness of regimes already under stress. In that environment, the appeal of a strong leader who claims he can “just fix it” becomes considerably higher, both to the population and leading business interests. Most of us accept the idea that free and fair elections by themselves are sufficient to ensure the legitimacy of a government. But, for most people, the legitimacy of the government depends as much or more on the extent to which the government protects their security and provides for their well being. Thus, when we see voters favor Trump on reducing inflation, we need to understand “inflation” more broadly to include insecurity generally, which is what Trump more credibly claims to address.

- Unemployment

In our culture, work is an essential aspect of identity. When the economy shut down in March/April of 2020, nations took one of two paths – subsidizing continued employment, as in much of Europe, or boosting unemployment insurance, as in the United States. We have memory-holed the psychic damage, widespread anxiety, and deracination that we caused by effectively firing more than 20 million Americans. Again, trauma leaves scars. Unemployment and economic insecurity always come with increased mortality, substance abuse, broken families, and domestic violence. To a great extent, economic insecurity is the psychological driver of deaths of despair.

- Expectations and the American Dream

For the cohort entering the workforce in the mid-2000’s, COVID marked the second catastrophic blow to their long term hopes and confidence in the future. As David Leonhardt points out in his new book, Ours Was the Shining Future: “A typical family in 2019 had a net worth slightly lower than the typical family in 2001. There has not been such a long period of wealth stagnation since the Great Depression.”4 And, citing research by Raj Chetty that while 92 percent of “children born in 1940 grew up to have higher household incomes than their parents,” that would be true for only 60 percent of Gen X’ers, and for only half of those born in 1980.

Despite every presidential candidate in every presidential race promising greater growth for the middle class, none have really delivered over the last five decades. We see this in the left panel of the next graph, which plots average real growth in disposable income per household since 1975. Note that this is adjusted for taxes paid and government benefits received. Moreover, the situation is even worse for average real household wealth, plotted in the right panel. Taking into account how household assets have not been meaningfully grown and that employment is broadly growing less secure, it’s not difficult to see how disappointing the neoliberal decades have been for working class voters, regardless of who is in the White House.

- Workplace Precarity

Elizabeth Anderson writes that most adults live their working lives under a “regime of private tyranny.”5 Indeed, she calls (non-union) corporations “communist dictatorships” that not only govern our work lives, but also have:

… the legal authority to regulate workers’ off-hour lives as well—their political activities, speech, choice of sexual partner, use of recreational drugs, alcohol, smoking, and exercise. Because most employers exercise this off-hours authority irregularly, arbitrarily, and without warning, most workers are unaware of how sweeping it is.6

Under the U.S. default of at-will employment, working people might be shocked to learn that they can be fired “for their off-hours Facebook postings, or for supporting a political candidate their boss opposes,” or even “because their daughter was raped by a friend of the boss.”7

Surprisingly (given its author, who has previously endorsed Trump), the recently published Tyranny Inc, suffers from no such political hemiagnosia:

This [workplace] tyranny subjugates us not as citizens but as employees and consumers, members of the class of people who lack control over most of society’s productive and financial assets. It is the structural cause behind much of our daily anxiety: the fear that we are utterly dispensable at work, that we are one illness or other personal mishap away from a potential financial disaster.8

Conclusion

In 2020, I cautioned against a “Great Forgetting” that seemed already to be setting in:

For Democrats and many progressives, first with Trump’s election and then with COVID, the lights came on, shining a spotlight on the contradictions between the world we live in and the stories we tell ourselves about that world. Many things that we accepted as natural were exposed for what they actually are. The reckoning with increasingly corrupt commercial and political arrangements as well as disintegrating social bonds felt as if it was coming due.

But when Biden was sworn in, and when all the purple state MAGA candidates lost in the midterms, we continued to “confuse momentary reprieves won at great cost against long odds with something like a new beginning. The tides didn’t breach the levees this time, but without repair, it won’t be long before they do.”

It is long past time we leave the bleachers and take the field ourselves. As the Declaration of Independence reads, “whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends [life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness], it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it.” We have a lot of alteration work ahead of us.

But for gerrymandering, it would have been all nine of the last nine, as Democrats won 51 percent of the vote but were left with only 46 percent of the seats (201 seats).

I recommend reading her Engine of Inequality: The Fed and the Future of Wealth in America which lays out clearly the consequences of delegating macroeconomic policy to the undemocratic Fed.

Mazzucato, Mariana. The Value of Everything. PublicAffairs. Kindle Edition.

Leonhardt, David. Ours Was the Shining Future (p. xxiv). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Anderson, Elizabeth. Private Government: 44 (The University Center for Human Values Series) (p. 6). Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

She asks us to “imagine a government that assigns almost everyone a superior whom they must obey. Although superiors give most inferiors a routine to follow, there is no rule of law. Orders may be arbitrary and can change at any time, without prior notice or opportunity to appeal. Superiors are unaccountable to those they order around. They are neither elected nor removable by their inferiors. Inferiors have no right to complain in court about how they are being treated, except in a few narrowly defined cases. They also have no right to be consulted about the orders they are given.” (Anderson, Elizabeth. Private Government: 44 (The University Center for Human Values Series) (pp. 39-40). Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

Anderson, Elizabeth. Private Government: 44 (The University Center for Human Values Series) (pp. 39-40). Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

Ahmari, Sohrab. Tyranny, Inc. (pp. xx-xxi). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

For my household, which was deeply affected by the 2008 recession, even making decent wages for the past few years we still have that sense of economic precarity. We struggle with such a deep reluctance to spend money on even quite necessary things, because now we know how arbitrary and capricious things are in America. You can do everything right and be good at your job, and still be thrown to the wolves through no real fault of your own, if the market demands it be so.

Mariana Mazzucato's insight you included is something I find myself constantly thinking about. "She astutely points out that modern economies reward activities that extract value rather than create it, which leads to obvious injustices."

Even in cases where we talk ourselves into investing the money in a needed purchase, it seems a foregone conclusion that every available option is now twice as expensive as it would have been if I could have afforded to buy it 5 years ago AND it's quality or reliability is going to be half what it once was.

The system of extraction is eating the middle class from both ends. We got stagnating wages for decades, while rents/profits on everything grew exponentially, AND the company shaved more nickles out of every purchase by cheaping out on materials, staff, assembly processes, and customer service on the back end.

It's easy to feel like you're working harder than ever and constantly have less to show for it. I can certainly understand the naive attitude that we should just burn it all down and start over from scratch.

Precarity is one of those words that may have resonance with political wonks, but does not pass the political p.r. test. Why not insecurity?