Beware of Mad Poll Disease In Good Times and In Bad

We have less than three months left. Polls still can't tell us anything we don't already know.

A year ago, I published “A Cure for Mad Poll Disease” as an antidote for the panicked reactions to the first New York Times/Siena and ABC/Washington Post polls showing Trump in a much stronger than expected position. The dramatic shift towards Harris now has many positively gleeful. So, today, I want to make clear that what I said in bad times is also true in good times: Horse race polls are opinion journalism, not science – even when the numbers are going your way.

I said before that we already know all that can be known, and all that we need to know – that who will win the Electoral College will most likely be decided by six states, with margins too small to be confidently measured even the week before the election, and that the winner will be determined by the margin of effort.

The New York Times has a new interactive with the dramatic headline, “How Harris Has Upended the Presidential Race” – but the interactive reveals nothing different than my February piece, “The Electoral College Landscape,” which I published with a nifty DIY spreadsheet that needs no updating six months later. Indeed, what makes stories like that “news” is commentators having been wrong about election dynamics in the first place.

If you have any doubt about whether horse race polling has eaten political coverage, consider the magnitude of how many surveys there are in FiveThirtyEight’s aggregating database. So far, that’s more than 2,000 surveys, reflecting 4.5 million interviews.

How Has All That Predicting Worked Out for Us?

Now, remember that the forecast below was made on the eve of the election in 2016. Let’s take a look at how Nate Silver’s forecasting performed at FiveThirtyEight in 2016 and 2020, and what his polling averages and forecasts at his new Silver Bulletin substack say now. (To be clear – much of what I argue in this post could be said of many others besides Silver.1)

The first two columns in the chart below reproduce Silver’s polls-only forecasts for 2016 and 2020, followed by the actual outcomes in those states and the difference between the two. The next column shows the states that were wrong at least once in those two elections. The payoff is the last two columns – Silver’s current polling averages, followed by what the actual margin would be assuming it is off by at least as much in the same direction as it was in his best 2016 or 2020 polls-only forecasts.

If Silver’s current polling averages hold, then Harris wins the Electoral College with 276 electoral votes, which is consistent with his estimates that she has a better than average chance of winning the Electoral College. But the last column shows that if his “80 days out” polling average is off by as little as his smallest previous error, Harris comes away with just 232 Electoral College votes. (On the other hand, if it is off by as much in the other direction, Harris is on her way to a landslide election.2)

Of course, I’m presenting this not to inform you of what Harris’ actual chances are, but to show you how foolish it would be to take these 2024 numbers seriously, no matter how good that “276” in the total line makes you feel.

Will the Electoral College Gods Smile on Us this Time?

In both 2016 and 2020, first Trump and then Biden won the states they needed to win the Electoral College by margins too small for even the “best” polling to detect.

It’s even more foolish to try to use national polling, as opposed to state polling, to feel confident about the outcome; we all know Democrats have lost two of the last six elections despite having won the national popular vote because of the Electoral College.

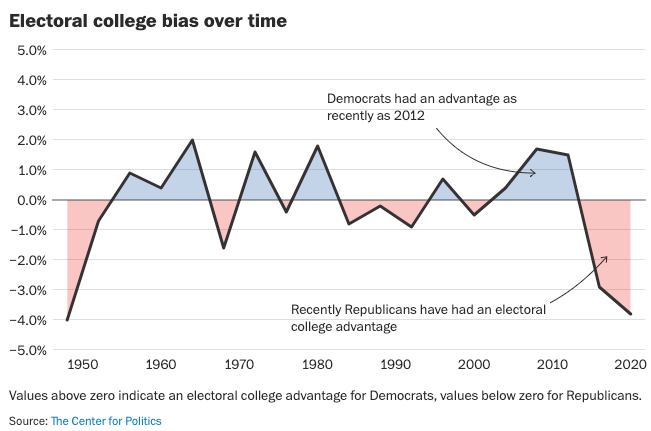

Nonetheless, we are told to pay attention to national polling. We hear a lot about the “Electoral College Penalty,” a metric that subtracts the winning candidate’s margin in the state that gives him an Electoral College majority from the margin he won the national vote by.3

The chart below shows the meandering record of the penalty since 1950:

It’s like the capricious will of the gods that ancient farmers believed explained the difference between their expected harvests and their actual ones, or their life prospects generally. As you can see, the Electoral College gods are fickle, sometimes cursing the Democrats and sometimes cursing the Republicans.

And this shouldn’t be surprising. I’m old enough to remember when the “Electoral College Penalty” wasn’t considered a predictive factor before Election Day, but rather a metric computed after the election as a way to quantify just how undemocratic the Electoral College is.

This is all comically ass-backwards. The Electoral College penalty will actually be determined by how many votes Harris wins in the states she carries compared to how many she loses in the states Trump wins. That’s it. All year, pundits have been saying they expect the Electoral College penalty will be smaller this election than it was four years ago – simply because they are expecting Biden (and now Harris) to do somewhat worse in those states than Biden did in 2020.

So, get a grip. You win the White House by winning the tipping point state, not by making sure you win the national vote by enough to protect yourself from the angry Electoral College gods. I’m sure that Jen O’Malley Dillon is spending her time on strategies to win in the battleground states, not to win the national vote by a large enough margin to satisfy the Electoral College gods. (Actually, if she ran up the score outside the battleground states, it would enrage the Electoral College gods, who would “punish” her with an even larger “penalty” than they had Biden in 2020.)

Even if there is no Electoral College penalty at all in November, the Electoral College scourge that first appeared in 2000 is sure to return in November if Harris wins. That scourge is the opportunity for lawfare. In 2020, Trump asked Brad Raffensperger to find him the 11,780 votes he needed to reverse Biden's Georgia win. Without an Electoral College, who could Trump have asked to find him the 7,059,526 votes needed to overturn the national election? Beginning in 2000, losing Republicans have seen the voters’ choices as the starting gun for lawfare and rampant toxic disinformation campaigns.

Repeat After Me: Politics Isn’t Sports

In his just published book On the Edge, Nate Silver makes a very important point about his 2016 projection, which was the most clicked forecasting site. He says he took a lot of shit he doesn’t think he deserves. His defense deserves serious consideration because it (probably unintentionally) says the quiet part out loud.

The reaction of many people in the political world to this forecast was: “Nate Silver is a fucking idiot.” But from my standpoint—and from the standpoint of people in the River, the landscape of skilled gamblers and like-minded folks that I introduced in the prologue—this was a damned good forecast. It was a good forecast for a simple reason: if you’d bet on it, you would have made a lot of money. If a model says that Trump’s chances are 29 percent and the market price is 17 percent, the correct play is to bet on Trump—big. For every $100 you bet on Trump, you’d expect to make a profit of $74.4

In other words, the benchmark against which Silver measures his models is not against the actual outcome, but against the odds being offered on betting markets. But, of course, very few of the many millions of clicks on his site in 2016 were election bettors looking for an edge at PredictIt.

Unfortunately, key political actors were relying on such polling and forecasts – including James Comey as he weighed the wisdom of making public his letter to Congress that he was reopening his email inquiry a week before the election:

Like many others, I was surprised when Donald Trump was elected president. I had assumed from media polling that Hillary Clinton was going to win.5

Earlier this year, Joe Kahn, the Managing Editor of the New York Times, cited polling results to defend his decision making about the Times’ priorities, revealing how central to his reasoning polling has become:

It’s also true that Trump could win this election in a popular vote. Given that Trump’s not in office, it will probably be fair. And there’s a very good chance, based on our polling and other independent polling, that he will win that election in a popular vote.6

Perhaps paradoxically, Nate Cohn just ended an informative piece on the accuracy of polling with this:

Despite this history, there’s still no guarantee that the Times/Siena data is correct. Even an unequivocally bad methodological decision — say, calling only landlines — can still occasionally yield a more “accurate” result if it cancels out a different kind of bias in another direction (say, Mr. Trump’s supporters being less likely to respond to a poll). Weighting on recalled vote is clearly far more debatable, but even if it is every bit as problematic it could still yield accurate results this cycle for the same reason. No one ever knows which polls — or which polling methodologies — will appear “right” or “wrong” until the election results begin to arrive.

This too gives away the game. Somehow, the sum of very reasonable caveats in such pieces never manage to add up to questioning why we should put polling at the center of our understanding of electoral politics in the first place.

This misplaced focus has a high cost. It translates into much more coverage of which candidates “we support” than of what we know about what the candidates will do if they are elected – the predicate for a democracy that depends on the consent of an informed governed to flourish.

Politics is not sports; wins and losses impact all of our lives. But when politics is covered like sports, we think like passive observers – as fans, when in reality we are all owners.

Weekend Reading is edited by Emily Crockett, with research assistance by Andrea Evans and Thomas Mande.

I foreground Nate Silver for several reasons: (1) conveniently, he has three consecutive, well documented forecasts; (2) his forecasts in 2016 and 2020 were the most popular; (3) in his new book, to his credit, he recognizes that what he does has been controversial, considers himself a public figure and welcomes critiques, and unlike all or nearly any others I might name, he came to election forecasting to monetize his skills, where the others began as reporters or academics.

This sentence was prompted by someone I asked to read a draft wondering if it might not be off by as much in the other direction. My first reaction was LOL, and I realized it would be useful to explain why I LOL’d. It actually points to one of the built-in reasons pollsters and forecasters can be as “close” as they usually are, at least when it comes to presidential elections in those states. Think about Wisconsin. In the last four elections, the top of the ticket margin was a point or less, and in 2022 against a very bad candidate it was less than 4 points. So, without reference to polling, you would be pretty confident that this year Harris could win by 7 points – the current polling lead plus the absolute value of the smallest miss over the last two presidential elections. There is absolutely no evidence in the world to make that seem anything other than preposterous. You have to ignore the realities on the ground of Wisconsin and presume that polling is our only way to make an estimate, and then embrace a loose idea of margin of error to think that it is anywhere near as likely that the error could be +6.1 as it is that it could be minus 6.1.

I am truly looking forward to the day when using “him” in sentences like this will no longer be accurate.

Silver, Nate. On the Edge (p. 14). Penguin Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Comey, James. A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership (p. 204). Flatiron Books. Kindle Edition.

In that interview, Kahn went on to say, “It’s our job to cover the full range of issues that people have. At the moment, democracy is one of them. But it’s not the top one — immigration happens to be the top [of polls], and the economy and inflation is the second,” showing again that he was relying on polling as an input.

This was a great read. Thank you.

So we have media outlets, - like the NYT as mentioned here - use polling results to drive narratives and framing, no matter any flawed methodologies - creating their content from said poll results - yet they are already creating the content - the polls themselves. Got it.