Breaking the Law: Trump Is the Means, Not the End

The Federalist Society coup, in 16 charts.

Going into last week’s oral arguments on Trump’s immunity appeal, it was widely believed that as a practical matter the appeals court decision would hold – that Trump did not have immunity for attempting to overturn the results of the election he lost and for inciting a deadly mob to prevent the Electoral College votes from being counted. At that point, it seemed clear that the only motive for SCOTUS to hear Trump’s appeal in the first place was to delay his trial. Indeed, there was no apparent justification for the Supreme Court hearing this appeal other than postponing the trial. After all, Justice Roberts has famously said:

If it is not necessary to decide more to dispose of a case, then it is necessary not to decide more.

Instead, as they have so many times before, the six Federalist Society justices1 opened the door to much darker possibilities. Astonishingly, they were more concerned with erring by setting a precedent that could open the door to frivolous partisan prosecutions by the Justice Department against a future president than they were about erring by setting a precedent that would close the door to accountability for the last president who actually attempted a coup. (Incredibly, the implication, an echo of MAGA paranoia, is that the Justice Department, the criminal justice system, and the jury system are less legitimate than the actions of the unnamed president.)

The Federalist Society Project

Right now there is a real risk that the raw offensiveness of the proceedings – the shock of hearing certain justices entertain the idea of allowing presidential lawlessness – will continue to distract us from the most lethal danger we face. That danger is the completion of the Federalist Society project: to replace America’s liberal democratic constitutional order with an illiberal, revanchist one that does not protect civil rights or constrain the worst excesses of capital, and that allows the Court to make policy without democratic accountability.

It’s a mistake to discuss Samuel Alito, Amy Coney Barrett, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, John Roberts, and Clarence Thomas as individual jurists rather than as politicians who were effectively “appointed” to the Court by the Federalist Society. Whatever your (justifiable) problems with any of those individuals, if they had not been confirmed, there were dozens more lined up on the Federalist bench who would not be doing anything substantially different. (To be clear, I am not saying that the justices have been bought off; I’m reasonably confident they believe in what they are doing. I am saying that they wouldn't be Supreme Court justices if they hadn’t been able to convince the MAGA/corporate judicial gatekeepers of their commitment to the cause.)

The Federalist Society justices are team players, not impartial umpires calling balls and strikes. The Federalist Society is the owner, with the undisputed power to put justices on a short list of acceptable nominees for Republican presidents—who reject that list at their political peril.

The history of the corporate and religious right campaigns to capture the courts and hijack democracy itself has been so exhaustively documented elsewhere that there’s no need to recite it here.2 What’s important to understand now is the result of that campaign. Since the Federalist Society was founded in 1982, the Court has transformed from an imperfect arbiter of genuine controversies to an agenda-driven, unelected lawmaking body whose decisions have systematically been opposed by the majority of Americans. As this post will show, Federalist Society majorities have acted with ever-increasing impunity to leverage the power granted to them by an ever-diminishing proportion of Americans, as reflected by the presidents who nominate them and senators who confirm them. Thus, it’s long past time to stop covering the Court as if it is anything other than an unaccountable super-legislature enacting an unpopular revanchist agenda.

In 2020, Harvard law professor Adrian Vermeule said the quiet part out loud:

If President Donald Trump is reelected, some version of legal conservatism will become the law’s animating spirit for a generation or more.

Trump Is the Means, Not the Ends

While it’s accurate to say that the Court is protecting Trump, doing so misses greater stakes, and obscures the motivations of at least a few of the Federalist Society justices, which is to secure for at least a generation what could eventually be called the Dobbs Court.

Consider that by 2028, Clarence Thomas will be 80 and Samuel Alito 78, and Sonia Sotomayor will be 73 and has a chronic health condition. That means that by 2028, Trump could make nominations that add up to a 7-2 Federalist Society majority, with John Roberts the only one over 65 years old. On the other hand, Biden’s second term nominees could constitute a 5-4 “Democratic” majority, with Elena Kagan the only one over 60 years old (68). The stakes are similar in terms of the federal appeals and district courts, where a second Trump term would likely provide Federalist Society majorities on even more of the circuits, and many of his second term appointments would be unqualified ideologues like Matthew Kacsmaryk. A second Biden Administration (with a Senate majority), however, could claw back Federalist Society majorities in several circuits.

It’s difficult to believe that the Federalist Society justices delaying the J6 trial were ignorant or indifferent to the fact that the success of their life’s project is on the line in November. Indeed, when Gorsuch said, “We are writing a rule for the ages,” he gave away the game: if they thought something this momentous was required, there is no legitimate explanation, other than delay, to explain why they didn’t grant cert in December 2023 when Jack Smith asked them to. Nor, for that matter, is there an explanation for why they took three weeks after the appeals court decision in February to grant cert, or to schedule oral arguments eight weeks after that.

The Constitutional Coup in 15 Charts

In this section, I’ll use a series of charts to show how successful, ahistorical, and anti-democratic the Federalist Society project has been. The key findings are:

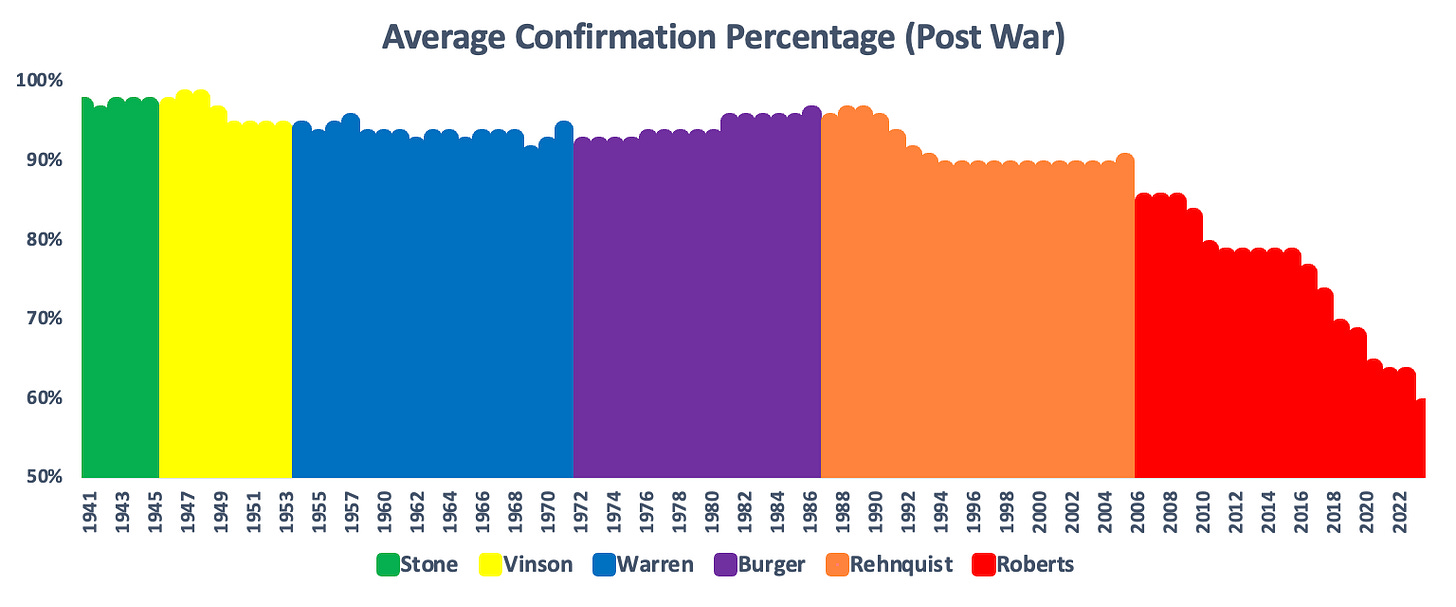

Confirmation becomes ultra-partisan. Before John Roberts’ nomination, justices were consistently confirmed in the Senate by solid bipartisan super-majorities; since then, none have been. (Charts #2 and #3). From 1954 until the Roberts nomination, the average percentage of senators confirming Democratic and Republican presidents’ nominees were nearly identical; since then, the average percentage of senators confirming Democratic presidents’ nominees has has been higher than the average confirming Republicans’ nominees (Chart #4).

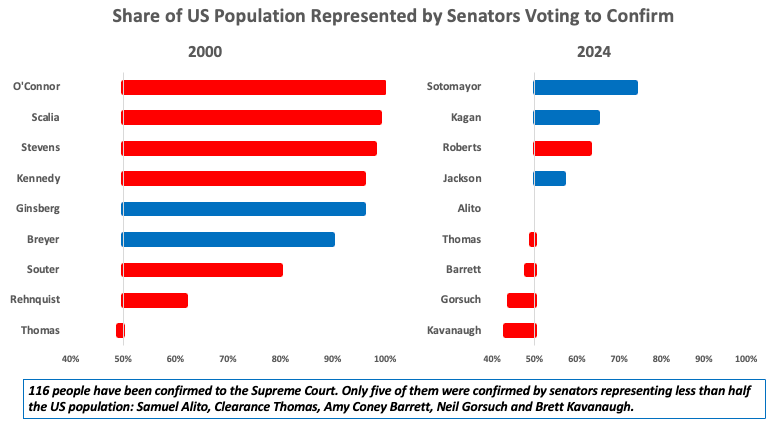

Minority confirmations. In 2000, every justice on the Court had been nominated by a president who had won the popular vote, and every justice but Thomas was confirmed by senators representing a majority of the US population. In 2024, three of the six justices were nominated by a president who lost the popular vote, and Roberts was the only Republican-nominated justice confirmed by senators representing a majority of the US population (Chart #5). (Every justice nominated by a Democratic president was confirmed by senators representing a majority of the US population.3) And, since at least 1994, the average share of the US population effectively represented when confirming Democratic nominees serving on the Court has significantly exceeded the average for justices nominated by Republican presidents (Chart #6).

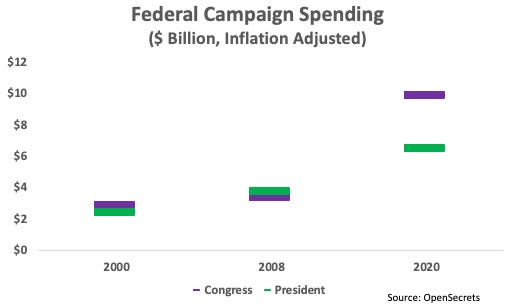

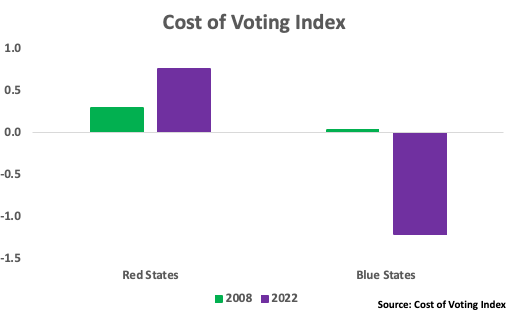

The umpires break the rules. The Roberts Court completely abandoned the idea of any sort of commitment to consensus, ramming through dozens of rulings that changed the political process, restricted civil rights, advanced the right’s social agenda, and favored corporations at the expense of working people and consumers (charts #7, #8 an #9). The effects have been immediate and powerful with campaign spending doubling (chart #10), the cost of voting skyrocketing in Red states (chart #11), and nearly restoring one party rule in the former Confederate states (chart #12).

Shredding the Court’s credibility. Through the Rehnquist Court, nearly half of Americans had “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in SCOTUS. Since 2020, that’s dropped by 20 points (chart #13), but, significantly, the decisions have increased the Court’s credibility with Republicans substantially (charts #14 and #15).

The Supreme Court of Red America. As recently as 2000, even the justices that gave us Bush v. Gore had been confirmed by senators representing regions in rough proportion to the country as a whole. But just two decades later, we can see that putting Thomas aside, the Supreme Court is now as divided sectionally as the Congress and as the Electoral College (chart #16).

Chart #1: Intention + Luck = Uninterrupted Republican SCOTUS Majority Since the 1970s

Republican nominees have been in the majority of every Supreme Court term since the 1970s, despite Democrats occupying the White House for 53 percent of the same period. In that period, intention and luck have both played a role. For example, Anthony Kennedy retired during the Trump Administration to ensure his perspective would endure. Ruth Bader Ginsburg did not when Obama was president and Democrats had a Senate majority. And, of course, Mitch McConnell refused to allow the Senate to vote on Merrick Garland’s nomination and then rammed through Amy Coney Barrett’s nomination after millions had already started voting in the 2020 election.

In the post-Reconstruction era, Democratic nominees have only had majorities for a few decades in the mid-20th century, which also coincided with landmark civil rights cases like Brown v. Board of Education.

In many ways we are seeing history repeat itself if we recognize the New Deal and the Civil Rights legislation of the 1960s as a second Reconstruction. After the first Reconstruction, the justices appointed to the Supreme Court favored railroad and other corporate interests and reflected an elite eagerness for sectional reconciliation. Those courts handed down some of its most infamous pro-corporate (e.g. Lochner v. New York) and anti-civil rights rulings (e.g. the Civil Rights Cases of 1883).

Charts #2, #3 and #4: Breaking the Nominating Process

It is important to remember that before the Federalist Society, the American Bar Association screened prospective nominees for their qualifications. There was no doubt that Democratic and Republican presidents preferred nominating justices that were generally more liberal or conservative, respectively, but it was in the context of the Court being an essentially conservative institution, in the sense that it was mindful of stare decisis and had a high bar for making dramatic or disruptive change. (See Chart #8 for more on how the bar for dramatic change got lowered.)

Justices no doubt brought something of prior ideology to judging the cases, but it was most definitely a policy making institution only as a last resort, when not resolving an issue was seen to be more problematic than resolving it. Even Richard Nixon, as John Dean details (with the benefit of extensive White House tapes) in The Rehnquist Choice, had a prosaic set of criteria when he nominated Rehnquist to replace John Marshall Harlan II. Those factors included electoral politics (which demographic voter block to appeal to), congressional relations (who key allies favored), ease of confirmation, and generally being conservative.

In 1987, President Reagan nominated Robert Bork to the Supreme Court, immediately setting off a firestorm of criticism. Republicans have claimed that the backlash broke the norm of deference to Presidents’ nominations. But in a way that echoes to this day, it is more accurate to say that the appointment was the norm breaker, as to this point, it was accepted that Democratic presidents would nominate those with liberal leanings, and Republican presidents would nominate those with conservative leanings, but that neither would appoint those intending to use the Court to revisit and change existing law, let alone legislate from the bench. Bork very flamboyantly broke that mold. The defeat of the Bork nomination served to more or less preserve that norm for another two decades.

It wouldn’t be until the George W. Bush Administration that Federalist Society endorsement would be a prerequisite for nomination. A key turning point was when Leonard Leo sunk Bush’s nomination of Harriet Miers for being insufficiently committed to the Federal Society agenda. Bush would not make that mistake again, as his next two nominees, John Roberts and Samuel Alito, more than met that standard. And, having cut his teeth in on the Bush v. Gore legal team, and having been a strenuous advocate of rolling back voting rights, Roberts was seen to be reliable.

The following chart displays the average Senate confirmation vote for the 9 justices sitting in each year, beginning in 1941. For the 64 years from 1941 through 2005, that average never dipped below 89 percent, and was at least 90 percent for most of the period. But that changed radically with the Roberts Court, and has been dropping even more precipitously since Trump was elected. (The y-axis begins at 50 percent because, by definition, no one can be confirmed with less).

Let’s take an even closer look at this. As we saw, until Roberts became chief, the average successful SCOTUS nominee could expect to be confirmed with 90 percent of the vote. But after Roberts became chief, every few years the average vote for confirmed justices dropped by a greater percentage than it had for over half a century, with key break points corresponding to first the Democratic wipe-out in 2010 (which made it clear that Democrats would not have 60 votes to overcome the filibusters that protected every SCOTUS decision), then Donald Trump’s election, and finally the ramming through of Barrett's nomination.

The next chart shows how nearly perfectly bipartisan the levels of support for justices serving on the Court were until 2006. Since then, the average confirmation support for those nominated by Democratic presidents has been consistently higher than for those nominated by Republican presidents, reflecting at least some resistance to the nomination of Federalist Society justices.4

Charts #5 and #6: Less Representative

As we know, the only justices serving who were nominated by a president that didn’t win the popular vote are Republicans: Gorsuch, Kavanugh and Barrett. And Roberts and Alito were appointed by Bush, but in the term after he lost the popular vote.

But now let’s look at how many Americans are actually represented by the senators who confirmed these justices – a “popular vote” count for SCOTUS confirmations, if you will. As the next chart shows, five of the six Federalist Society justices on the Court were confirmed by senators representing less than half the US population. Only John Roberts was confirmed by senators representing a clear majority of Americans. The panel on the left shows how dramatically different that was just 24 years ago, when, with the exception of Clarence Thomas, every justice on the Court was confirmed by senators representing at least two thirds of the US population, and six were confirmed by senators representing 90 percent of the US population.

That justices nominated by Democratic presidents have been confirmed by senators representing a greater proportion of the US population has actually been a consistent pattern since at least 1995. The following chart shows the average percent of the population represented by senators voting for both the Democratic and Republican nominees serving that year. Since 2017, that margin has widened.

Charts #7, #8, and #9: The Umpires Break the Rules

Until Bush v Gore, more often than not, when the Court handed down rulings with profound implications for the life of the nation, especially when those rulings overturned previous ones, the justices strenuously sought to come as close to a consensus as possible to demonstrate to the nation that regardless of their having been appointed by presidents of different parties, and despite having been seen to have ideological differences, they agreed on the matter at hand.

Major rulings decided unanimously include McCullough v. Maryland (1818), Schenck v. United States (1919), Loving vs Virginia (1969) and United States vs Nixon. (Indeed, contrast the ruling in US vs Nixon – when five justices, including the Chief Justice, voted against the president of the party that appointed them – with the ruling of the five justices appointed by Republican presidents in Bush v Gore.)

Since Bush v. Gore, however, and especially under the Roberts court, Federalist Society majorities started abandoning this norm of consensus, routinely handing down narrow decisions with major policy implications that benefitted revanchist interests. In 2018, the American Constitution Society compiled a list of 73 cases in which the Roberts court has handed down narrow 5-4 rulings that advanced one of four MAGA-friendly agenda items. And, of course, there have been many more since then.

When it came to overturning major civil rights precedents in particular, there was a dramatic difference in consensus-building, or lack thereof, between the civil rights-era courts (Warren and Burger) and the civil rights counterrevolution courts (Rehnquist and Roberts). That’s not surprising given Rehnquist's participation in voter suppression efforts in Arizona and his memo to Justice Jackson, for whom he was clerking, to justify upholding Plessy during consideration of Brown v Board of Education.

The overwhelming majority of civil rights related precedents overturned by the Warren and Burger courts were decided with at least 7 votes. As well described in various accounts, Chief Justice Earl Warren worked strenuously to fashion a unanimous opinion in Brown, which included the assent of Justices Hugo Black (formerly a senator from Alabama) and Stanley Reed, who initially said he “opposed abolishing segregation.”5 By contrast, none of the civil rights precedents overturned by the Rehnquist Court, and fewer than 1 in 5 of those overturned by the Roberts Court, had as many as 7 votes.

But it’s even worse than that. Fewer than 1 in 5 of the civil rights precedents overturned by the Warren and Burger courts were by a single vote margin, and every 5-vote majority case included justices appointed by both Democratic and Republican presidents. On the other hand, 3 in 5 civil rights precedents overturned by the Rehnquist and Roberts Courts were decided by 5-4 margins along strictly partisan lines. (And all but one of the civil rights precedents overturned 6-3 were strictly partisan, as there were six Republican-appointed justices at that time.)

In the next graph, we can see that for other cases that overturned precedents, the Rehnquist Court was not that different from the two before it – as with the previous two courts, more precedents were overturned with 7 or more votes than by 5-4. Here again it’s the Roberts Court that breaks with the past, as even beyond civil rights cases, a greater share of the overturned precedents were by 5-4 than with 7 or more votes.

Charts #10, #11 and #12: The Demons Loosed

Taken together, the Federalist Society justices’ election-related rulings have completely transformed the electoral process.6 The next graph shows that, adjusted for inflation, total spending on congressional and presidential campaigns was barely more in 2008, the last presidential election before the Citizens United ruling, than it was in 2000. But in 2020, spending for the presidential campaign was nearly twice what it was in 2008, and spending for congressional campaigns more than twice what it was in 2008. Moreover, studies have consistently shown that Citizens United significantly increased Republicans’ success in state legislative races. For example, this study “analyzed data from more than 38,000 state legislative races between 2000 and 2012, in both groups of states.” It concluded that “The chance of Republican candidates winning state legislative seats increased by about four percentage points on average as a result of Citizens United,” findings confirmed by a subsequent study.

After Barack Obama’s victory in 2008, Red states began passing restrictions to voting which were upheld by the Federalist Society justices, and then, of course, in a series of cases beginning with Shelby, they all but repealed the Voting Rights Act. Scholars have tracked the “cost of voting” since the 1990’s by scoring each state based on metrics such as average wait time at a polling place or whether the state allows early voting. As you can see in the graph below, the “cost” of voting dramatically increased between 2008 and 2020 in Red states while decreasing substantially in the Blue states. (More here.)

Finally, when you all but remove the steps taken to dismantle one party rule in the former Confederate states, not surprisingly, you open the door for one party rule again. The following chart dramatically shows how, again with the Supreme Court’s assistance, MAGA has succeeded at rerunning this post-Reconstruction playbook. The top half of the chart shows unified control of the state government (both legislative chambers + governor) and the bottom half shows control of both legislative chambers. Blue means that Democrats controlled, Red that Republicans controlled, and white either that one party held each chamber, or that one party held both chambers and the other held the governorship.7 The last 88 years are divided into three periods: (1) The Jim Crow Era (1932-1968) in which Democrats were the party of segregation and Jim Crow; (2) the Voting Rights Era (1968-2008) when almost immediately the two party competition emerged (think Jimmy Carter, Lawton Chiles, Bill Clinton, Zell Miller); and (3) the MAGA Era (2008 - Present) in which electoral competition was snuffed out. These states are now nearly as red as they were blue during the Jim Crow Era.8 And we know that this will almost certainly be the case for the rest of the decade, given the recent round of gerrymandered redistricting that has been greenlit by SCOTUS rulings.

Charts #13, #14 and #15: The Collapse of Credibility

Outside of MAGA bubbles, it’s generally understood that Americans are losing (or have lost) faith in the Supreme Court as an institution. We can see this visualized dramatically in the chart below, which shows Gallup poll results on how much confidence people have in the Court as an institution – not just whether people like or dislike the decisions the Court has been making lately. When we look at the long-term trends in public confidence, we can see that the “crisis of legitimacy” has been a longstanding feature of the Roberts Court.

When we observe the Court is pursuing “a very unpopular agenda,” we must realize that what is unpopular with most Americans is actually very popular with the constituencies that put the Federalist Society justices on the court in the first place.

Consider Gallup poll results that show that 60 percent of Republicans believe ideology of the “Court is about right,” while an overwhelming majority of Democrats think it is too conservative, as do a plurality of independents:9

This next chart is particularly striking. It shows the Supreme Court’s job approval among Republican vs. Democratic voters over the last six presidential terms. We would expect to see the Court with higher approval among Republicans during Republican presidencies, and higher approval among Democrats during Democratic presidencies. But with Biden’s term, the pattern is exactly reversed. Clearly, both Republican and Democratic voters understand that the Court is advancing the MAGA Republican agenda, and are reacting accordingly.

Chart #16: The Supreme Court of Red America

But if we say that “the American people” have lost faith in the Court, we are missing something important. We are thinking of the United States as being a single united country – which, as I’ve written extensively, is not the case in practice. We are so starkly divided by region that life in Red vs. Blue states is like life in two different countries.

As recently as 2000, even the justices that gave us Bush v. Gore had been confirmed by senators representing regions in rough proportion to the country as a whole (left panel). But just two decades later, we can see that putting Thomas aside, the Supreme Court is now as divided sectionally as the Congress and as the Electoral College.

Bonus Chart: The Federalist Society Social Scene

OK, this one isn’t a chart – but it’s a visual we should never forget when thinking about the current Court. The six Federalist Society justices are more concerned with boosting their credibility with Republicans and Trump than they are with mainstream legal scholars, Democrats, or independents. And even when they’re not on fishing trips or extravagant vacations, those justices mostly live in a social world that lauds the decisions most of us find so abhorrent, which is well documented in The Company they Keep.

Conclusion: The Ship of Theseus

A long standing philosophical question was most famously posed as a thought experiment about the Ship of Theseus. In Greek mythology, Theseus rescued the children of Athens from King Minos after slaying the Minotaur. It was such a momentous achievement that for hundreds of years, Athenians would sail the ship to Delos to commemorate the achievement. But since the ship was used for so long, they had to keep replacing planks in the ship – until, eventually, not a single piece of wood from the original ship was still there. Was it still Theseus’ ship? At what point was it no longer Theseus’ ship? More recently philosophers have broadened the thought experiment to the replacement of planks generally, rotting or not.

This is a question we must pose to the media (and ourselves), as the Federalist Society justices that have hijacked the Supreme Court replace plank after plank out of our basic social contract:

The rich and corporations can spend as much as they want to influence our elections. Is it still America? Politicians can draw the districts that insure their re-election. Is it still America? Women do not have reproductive freedom. Is it still America? A president can order up a coup and not go to trial for it until years later (if at all). Is it still America?

Weekend Reading is edited by Emily Crockett, with research assistance by Andrea Evans and Thomas Mande.

I call them “Federalist Society justices” because they have all been affiliated with that organization at some point, and they all had to be approved by the Federalist Society as an effective prerequisite to being nominated by a Republican president.

See works such as Jane Mayer’s Dark Money, Nancy MacLean’s Democracy in Chains, Anne Nelson’s The Shadow Network, Alexander Hertel Fernandez’s State Capture and Sheldon Whitehouse’s Captured and The Scheme: How the RIght Wing Used Dark Money to Capture the Supreme Court.

To calculate this, we added up the number of people represented by each senator who cast a vote to confirm the nominee (the population of their state divided by two), and then divided this sum by the total US population at that time.

Some might argue that this is simply because Republican senators are less ideological than Democratic senators, and more willing to give Democratic nominees the benefit of the doubt. But any objective examination of the records of those appointed by Republican and Democratic presidents since 2000 makes it clear that Democratic nominees have been much more moderate and judicially humble. Of course, even entertaining this argument means ignoring the fact that Republican presidents have, for example, pledged to only nominate those who would overturn Roe v Wade.

Simple Justice (Richard Kluger) p. 598

Voting Rights

Crawford v. Marion County Election Board. (2008) In a 6-3 decision, the centrist Stevens upheld the Indiana voter ID law. (Subsequently, Stevens regretted his position, reflecting that it was “a fairly unfortunate decision.”)

Shelby County v. Holder. (2013) In a 5-4 decision, Roberts declared section 4 of the Voting Rights Act unconstitutional. Section 4 provided the basis for determining which states were covered by pre-clearance (Section 5).

Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Institute. (2018) In a 5-4 decision, Alito upheld Ohio’s extraordinarily aggressive voter file purge practices.

Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee. (2021) In a 6-3 decision, Alito dramatically reduced the scope of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

Gerrymandering

Vieth v. Jubelirer. (2004) This was a challenge to a blatantly gerrymandered map drawn by a Republican trifecta. In a 5-4 decision not to intervene, Scalia wrote that all claims related to political (but not racial) gerrymandering should be nonjusticiable, meaning that courts could not hear them.

Rucho v. Common Cause. (2019) In a 5-4 decision, Roberts slammed shut the possibility of federal court review of claims of partisan gerrymandering, indicating that the framers intended this be left to state legislatures.

Wisconsin Legislature, et al. v. Wisconsin Elections Commission, et al. (2022) In an unsigned decision issued through the shadow docket, the court overturned a state court ruling that the creation of an additional majority-Black district was justified.

Campaign Finance

Buckley v. Valeo. (1976) Ruled that certain campaign spending was protected as “speech”under the First Amendment, and therefore could not be capped.

First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti. (1977) In a 5-4 decision, Powell extended Buckley to overturn restrictions on corporate spending on ballot initiatives.

Federal Election Commission v. Wisconsin Right to Life. (2007) In a 5-4 decision, Roberts held that certain limitations on issue ads were unconstitutional.

Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission. (2010) In a 5-4 decision, Kennedy ruled restrictions on independent spending by corporations unconstitutional under the first amendment.

McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission. (2014) In a 5-4 decision, Roberts held that aggregate limits on political giving by an individual are unconstitutional.

Technical note - the chart is based on control in each presidential election year beginning in 1932. It was not worth the effort to gain the precision to mark dates for state legislatures that are elected in odd years since doing so would not change the conclusion. Also, note that the charts reflect who controlled the legislatures in the election year, not who won the election that year.

To be clear, I am not arguing that their ambition is to literally return to the objective conditions that prevailed in the Confederate states in 1965. Too much has happened since then. But that they have not re-established the ante-VRA Jim Crow regime in each of its particulars should be of no more relief than it would be to view Jim Crow as “better than” slavery.

Unfortunately, Gallup doesn’t publish responses to the “confidence” question broken down by partisanship.

My reading strongly suggests that Trump has become too demented to run the country.

https://thinkbigpicture.substack.com/p/john-gartner-trump-cognitive-decline

I suspect that should he end up in the White House again, various high placed federalist society characters will run his presidency in somewhat the manner that Edith Wilson ran her husband's presidency after he had a stroke.

And I suspect the federalist society people like it that way.

Ever since the open arguments in the Trump immunity case, I've been wishing just one of the more liberal justices had pointedly asked, "How much immunity does this court want to give to Joe Biden?"

Because, despite the willful insistence by the right wing end of the bench to go on a flight of fancy about potential future presidents & their potential future crimes & prosecution, it might have helped strike a sober point about how their impending foolishness *could* be used by a president they don't favor politically.