Shelby County Opened the Door to Modern-Day Poll Taxes

How MAGA voter suppression really works.

We are just a few weeks past the anniversary of “Bloody Sunday,” when civil rights activists, including John Lewis, were brutally beaten upon attempting to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama to begin their march to Montgomery for voting rights. We think of the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) just five months later as a shining moment in American history, when it appeared that America might be ready to finally make good on the “promissory note” King had spoken of two years earlier.

Yet somehow, 59 years later, we have accepted and moved on from the Supreme Court gutting the VRA in its 2013 Shelby County ruling. Worse, many believe political science has “proven” that voter suppression laws enacted since Shelby have not actually suppressed the vote.1 Recently, however, the Brennan Center released a groundbreaking report, “Growing Racial Disparities in Voter Turnout, 2008–2022,” which concluded the opposite – that the racial turnout gap2 “is increasing nationwide, especially in counties that had been subject to federal oversight until the Supreme Court invalidated preclearance in 2013.” (It was written up in the New York Times here.)

The Brennan Center study is a work of extraordinary and vital scholarship, based on substantially more data over a longer period of time than other studies that appear to show little or no impact on turnout from voter suppression measures. Rather than trying to assess the impact of specific voter suppression policies in isolation, it shows the cumulative harm that resulted once states and counties were free to change their voting rules without proving that those changes would have no discriminatory effects.

In this post, I will offer original analysis that not only corroborates Brennan's findings, but also illustrates a key dimension of how voter suppression works in the real world – a sort of generational replacement, where older and established voters keep up their voting habits, while new restrictions stymie younger voters. (For convenience, “younger” voters are Millennials and Gen Z and “older” voters are Boomers, Greatest, and Silent Generations.) I will also explain how reducing turnout among certain groups is not the only effect of voter suppression. Restrictive voting laws also make it more costly to vote, both for individuals and for civil society.

I have been reluctant to post on this topic because the minute we debate how much impact the stricter voter rules have had, we allow that any impact is tolerable. However, it’s important to point out that even on its own terms, the argument that voter restrictions do not meaningfully reduce Black turnout is simply incorrect. My analysis and Brennan’s both show clear impacts on turnout for voters of color.3 But, again: It should not matter whether voting restrictions result in relatively fewer Black people voting if they disproportionately make it more burdensome for them to vote, either financially or in time spent. That’s just a poll tax by another name. Period.

Asking “how much impact” is also troublesome because in every other instance when we are asked to accept compromises to our individual liberties, it is for the sake of a higher public purpose. But in this case, the “higher public purpose” (“election integrity”) is the wholly unsubstantiated invention of the Republicans and MAGA activists who themselves are the greatest threat to election integrity. Their argument is, “The only way to restore (white) voter confidence in the integrity of election results (which they had before our lies destroyed it) is to enact additional ‘safeguards’ (making it more difficult for voters favoring Democrats to vote and have their ballots counted.)”

How Voter Suppression Actually Works

On first blush, you might expect voting restrictions to start suppressing Black voters immediately. But let’s take a step back. In reality, those who had been regular voters before the restrictions were enacted are the least likely to be affected by suppressive efforts. At that point, those voters were habitual voters. Even if it took a little longer to vote or was a little more inconvenient in the next election, you wouldn’t expect a big change in behavior. On top of that, in 2012 (the last election before Shelby), nearly half of African American voters were Boomers or older – the generations that either won the right to vote, or were old enough to remember it happening. So, unsurprisingly, most have continued to vote reliably; at a minimum it was a personal habit, one that was reinforced by social expectations. (This is well documented in Steadfast Democrats: How Social Forces Shape Black Political Behavior.)

Furthermore, as empirical work by André Blais and Christopher H. Achen shows, the electorate consists of two types of voters – those who have a sense of “civic duty” and will likely vote regardless of what’s at stake in any particular election, and those whose turnout depends on the stakes as well as perceptions of aggregate turnout. The analysis by Blais and Achen convincingly shows that a “turnout model misses something fundamental if it does not take into account the effect of civic duty.”

With that in mind, I am going to illustrate what actually happened using the Catalist voter files from the 2012 election and the 2020 election. I’m going to define four categories, from jurisdictions most likely to least likely to be suppressing Black votes:

States covered by the Voting Rights Act4

States that were not covered by the Voting Rights Act, but where Republican trifectas have been restricting voting rights.5

Counties covered by the Voting Rights Act but not in covered states.6

All other states

Common sense would tell you that voter suppression has its greatest impact on those for whom voting has not been established as a habit, and on those whose social groups feel less of a “civic duty” to vote. Thus, you would expect that voter suppression tactics would have the greatest impact on younger generations. You would also expect that the depression in Black voting would be greatest for the youngest generations and would be more pronounced in counties in which voter suppression was practiced after 2012.

And that is exactly what happened between 2012 and 2020, as Millennial and Gen Z voters made up an increasing share of the Black eligible population. (By 2020, Boomers, Silent and Greatest Generation voters were only a third of the Black electorate. For Gen X, turnout rates and changes in the racial turnout gap consistently fall in between those of younger and older voters.)

As you can see, Black Gen Z/Millennial voters were far more impacted in the three more suppressive categories than elsewhere. There was also virtually no change in the racial turnout gap for older voters outside the suppressive jurisdictions. Furthermore, more restrictive jurisdictions had a wider gulf in participation between older and younger Black voters.7

What Matters: The Cost of Voting

The evidence is unambiguous that Republican voting restrictions have made it more costly to vote – in money, time, or both – since Shelby. For example, getting the “right” ID costs both time and money, and numerous studies show that people of color are significantly less likely to have the kind of identification mandated by most voter ID laws. Longer lines or fewer options for voting certainly cost time, which is also money for hourly workers taking time off. And so on. Many studies try to assess the impact of particular voter suppression policies rather than evaluate the cumulative harm from the entire regime of voter suppression. Such an approach also ignores what is unwritten in the policy specifics – the intentions of local election administrators, which, of course, are highly correlated with the intentions of the formal changes.

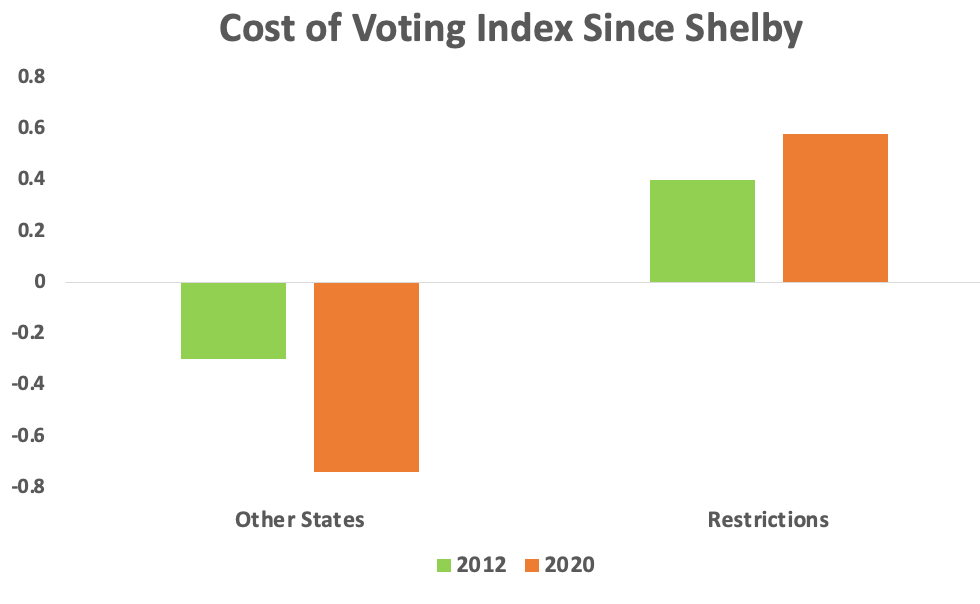

Scholars have tracked the “cost of voting” since the 1990’s by scoring each state based on metrics such as average wait time at a polling place or whether the state allows early voting. As you can see in the graph below, the “cost” of voting dramatically increased between 2012 and 2020 in the states that were originally covered by the VRA (whether it was the entire state or only certain counties) and in those states with Republican trifectas, while dramatically decreasing elsewhere.8

The very recently published The Cost of Voting in the American States, by Michael J. Pomante II, Scot Schraufnagel, and Quan Li, is an exhaustive, rigorous exploration of the cost of voting going back decades.9 It is worth quoting their conclusions, which found that Obama’s election triggered Republicans to push more restrictive voting rules, and that the trend worsened after Shelby:

Our results uncover evidence in support of the “racial threat” theory. … Moreover, we know that Republican-leaning states became more restrictive after the country elected Barack Obama, the first Black president. Before the 2008 election, there was a negative link between COVI values and a larger percentage of GOP members in each state’s legislature. Put differently, in the earlier period, the GOP, on average, was associated with a less restrictive electioneering posture. The bivariate and the statistically significant relationship between the GOP and election restrictions does not materialize until after Obama’s electoral success.

Moreover, in the aftermath of the Supreme Court ruling in Shelby County v. Holder, and in time for the 2016 election cycle, we witness the relationship between GOP control and a more restrictive climate grow even stronger. The 2016 election cycle was the first to allow states with a history of racist policies to change their laws without preclearance or oversight from the federal government. Yet, before the landmark 5–4 Supreme Court decision, we found evidence that the Republican Party was associated with more costly voting in states with larger Black populations and growing Hispanic populations.10

Again, these irrefutable increases in the cost of voting constitute a poll tax, and as such should be the beginning and the end of the answer to whether the voter restrictions enacted over the last dozen years are legitimate.

Voter Suppression = Democracy Suppression

As bad as it is to assess voter suppression only in terms of whether it’s effectively reducing Black turnout, insult is added to injury when such arguments ignore the other ways in which voter suppression undermines democratic elections. In this section, I’ll name a few.

A Poll Tax on Civil Society

Voting rights groups will have to spend more resources on making sure affected voters can cast a ballot. Nonpartisan organizations seeking to close the racial voting gap, and Democratic campaigns attempting to do the same, easily spend in excess of $100 million per cycle to register and turn out voters of color beyond what it would cost if all voters had equal access to register and vote.

Exploiting Racial Divisions

Voter suppression proponents spread the fiction that their laws are necessary because voter fraud is rampant – specifically, voter fraud by people of color. People of color are either named explicitly (as with false claims that undocumented Latino immigrants are illegally voting en masse), or in thinly veiled euphemisms like “Democrat cities.”

These fictions impugn people of color as being untrustworthy at best, and outright evil and deceptive at worst. They feed and fuel lies about Black, young, Native, and new Americans that quite literally land them in prison for innocent mistakes; meanwhile, white people who commit actual documented voting crimes get slapped on the wrist. Consider how all of this might affect voters in the targeted communities. Not only do they see themselves targeted; they might lose confidence in the legitimacy of the whole process when the slanders against them both become the warrant for making it more difficult for them to vote, and are insufficiently resisted by others despite being executed in so blatantly undemocratic a fashion.

Moreover, when Republican legislatures enact voting restrictions, they create a no-win choice for Democrats. By advantaging white voters in a blatantly anti-democratic way, Republicans make it seem to white voters that Democrats are playing the “race card” if they object. But if Democrats don’t object, they will rightly appear to be unconcerned with the rights of Black voters. To the extent Democratic candidates are rallying Black support, they are often seen as ignoring other “more important” issues like jobs or inflation. This is especially problematic for Black Democratic candidates running statewide. And, as mentioned above, voter restrictions impose unnecessary extra costs on Democratic campaigns seeking to turn out people of color.

Undermining Free and Fair Elections

Campaigns to restrict voting poison confidence in election outcomes by manufacturing and amplifying lies about voter fraud. Indeed, this has become so acute that essentially a third of the population (MAGA Republicans) now routinely disbelieves election results when their candidate loses.

The “voter fraud” fiction has been deliberately created for the purpose of helping Republicans win. Consider this sampling of saying the quiet part out loud:

In 1980, Paul Weyrich, Moral Majority leader and co-founder of the Heritage Foundation, warned a crowd of “conservative Christians” about the problem of “wanting everyone to vote.” Weyrich said: “I don't want everybody to vote. Elections are not won by a majority of people, they never have been from the beginning of our country and they are not now. As a matter of fact, our leverage in the elections quite candidly goes up as the voting populace goes down."

In November 2012 Jim Greer, the former chair of the Republican Party in Florida, told the press that the goal of the passage of restrictions on early/absentee voting and voter registration was to make voting more difficult and inconvenient. He expounded that more convenient voting “is bad for Republican Party candidates.”

In 2013 Pennsylvania House Majority Leader Mike Turzai boasted that the state’s new voter identification law intended to “allow Governor Romney to win the state of Pennsylvania.”

In April 2016 Wisconsin State Representative Glenn Grothman bragged that 2016 would be different from previous elections because “now we have photo I.D., and I think photo I.D. is gonna make a little bit of a difference.”

In no case are state voter restrictions enacted with bipartisan majorities, and in nearly all cases they are enacted without a single Democratic vote. This makes equal voting rights seem like a partisan issue, when in fact they are the prerequisite for a functioning democracy.

Conclusion

Some analysts presuppose that for voter suppression to “matter,” the effect must be sufficiently large to swing an election. But the idea that there is an “acceptable” level of voter suppression is antithetical to what it means to live in a pluralistic democracy with equal voting rights for all. For many who make these arguments, the threat to democracy is not voting restrictions, but those who complain about them; white voters’ (fabricated) anxieties about voter fraud seem to matter more than the very real threats to Black voters’ equal democratic participation.

Since Obama’s election, Republicans have fairly succeeded in returning the South to a one-party region, and reversing progress on civil and human rights. Voting restrictions have been one element of that program. In that context, it’s even more bizarre to question one element of their comprehensive program in isolation.

Somehow, we’ve gone from condemning legislation with discriminatory effects on the cost of voting regardless of its stated intent, to minimizing the import of legislation enacted with discriminatory intent because it doesn’t seem to have a significant impact on partisan outcomes.

The purpose of elections is to establish the consent of the governed. Restricting voting in any way that has foreseeable (let alone intended) disproportionate consequences is by definition anti-democratic. There is but one side to this question.

Some examples of this type of coverage: The New Voting Restrictions Aren’t as Restrictive as Many Think - POLITICO; The silver lining of voter ID laws: they aren’t effective at suppressing the vote - Vox; Opinion | This Is One Republican Strategy That Isn’t Paying Off - The New York Times; Georgia’s Election Law, and Why Turnout Isn’t Easy to Turn Off - The New York Times

The racial turnout gap is defined as the turnout rate for white voters minus either the turnout rate for African American, Latino, AAPI, or all “non-white” voters collectively.

In this post my focus is voter suppression of Black voters. My argument holds for any group targeted for voter suppression, but because my purpose is to show why we should not be debating the impact of voter suppression on turnout at all, cycling through the same analysis for other groups would be counterproductive. That said, for the reasons I lay out the Latino turnout gap is much larger than the Black turnout gap because younger voters comprise an even greater share of Latino voters than Black voters. Unlike Latino and African Americans, two thirds of the AAPI population reside in states that were never covered by the Voting Rights Act.

The states covered in entirety by section 5 of the VRA were Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia.

States that were not covered under section 5, but that had a Republican trifecta post-Shelby and passed voting restrictions are: Arkansas, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Missouri, Montana, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Utah, Wisconsin, Wyoming.

A number of counties outside the South were covered. Many of them have been rehabilitated by progress in their states. As a group average, they are likely to be less restrictive than the first two categories.

There was already a generation gap in the racial turnout gap in 2012, as the oldest generation of Black voters, who had won the right to vote in their lifetime, were actually voting at a higher rate than white voters of the same age.

I combine the three categories for clarity.

Pomante, Michael J.; Schraufnagel, Scot; Li, Quan. The Cost of Voting in the American States (Studies in Government and Public Policy) (pp. 140-141). University Press of Kansas. Kindle Edition.

Pomante, Michael J.; Schraufnagel, Scot; Li, Quan. The Cost of Voting in the American States (Studies in Government and Public Policy) (p. 117). University Press of Kansas. Kindle Edition.

Well researched and persuasively argued. I’d give it an A+.

Great piece, thanks. One more bullet you could add in your last section before the conclusion: GA Gov. Brian Kemp said the quiet part out loud about SB 202, the 2021 omnibus voter-suppression bill: “I was as frustrated as anyone else with the results [of GA’s 2020 election], especially at the federal level. And we did something about it with Senate Bill 202.”

https://www.georgiademocrat.org/kemp-admits-sb-202-was-result-of-frustration-with-2020-election-results/