Congressional “Class Inversion” or Sectional Reversion?

Partying like it's 1928.

In the last few months, a number of thoughtful pieces have addressed the idea that there is a sort of “class inversion” in the House of Representatives, whereby Democrats are now representing wealthier and more educated districts than in previous decades, and Republicans are now representing more working-class and less educated districts.1 Unfortunately, these pieces have consistently missed a defining factor driving this reversal – the regional realignment of the Democratic and Republican Parties. Calling this development a “class reversal” reinforces the prevailing, but dangerously misguided, narrative that our toxic divisions are primarily a backlash against the over-woke, over-educated white liberals who have captured the Democratic Party.

I’m going to offer another way of looking at the results we’ve been hearing about. The factors that I am going to list are all part of a larger, coherent, interconnected process, but for clarity have to be first listed separately.

Factor One: White Evangelicals Quit the Democratic Party

As recently as 2008, Democrats represented 27 of the 87 congressional districts constituting the top quintile of white Evangelicals, and 61 of the 174 congressional districts in the top two quintiles. (The 435 congressional districts can be divided into quintiles of 87 districts each, which is how I will refer to them going forward.) By 2020, Democrats represented only 7 districts (8 percent) in the top quintile. In 2010, Democrats lost 17 of the 27 seats they had previously held in the top quintile and 35 of the seats they had held in the top two quintiles. Now, it may be fair to say that Democrats lost those seats because they were too socially liberal – but let’s be clear that if we do so, we accept the framing that it is a “socially liberal” position to acknowledge the legitimacy of a Black president.

In 2008, the average median household income (MHH income) in Democratic districts was $53,000, or about $2,500 less than what it was in Republican congressional districts. But, because the average MHH in Democrats’ top-quintile Evangelical districts was substantially less ($42,000), the loss of those districts simultaneously raised the MHH income of the districts still represented by Democrats and lowered the average MHH income of Republican-held districts, closing the gap to to just $350 (no missing zeros).

In other words, in part, what is being characterized as a “class inversion” is not really about class in any conventional meaning of the word (something to do with economics or work), but about an increasingly powerful backlash by Christian nationalist institutions expressing themselves politically. Thus, the “class” inversion can be explained in part by white Evangelical districts consolidating in the Republican Party – a trend which began in 1994 and then was fairly completed in 2010. Perhaps it’s just me, but this looks more like the consequences of action by the most important civic institutions in the Red states (churches and associated organizations) than anything to do with being “working class.”

Factor Two: Democratic Districts Have Been Doing Better Economically than Republican Districts

Four hundred twenty three, or 97 percent of all congressional districts, can be linked to representing the same place today as they did in 2002.2 (The other 12 are mostly new districts added by the 2010 Census.) Of those 423 districts, 311, or 73 percent of them, were represented by the same party in 2020 as they were in 2002.

The consistently Democratic districts have done better economically than the consistently Republican districts. If we compare how those consistent districts have fared over the 18 years from 2002 to 2020, we can see that the consistently Democratic districts saw much greater growth in average MHH income than those that stayed Republican – a 51 percent increase versus 41 percent, or nearly $6,000 more in median household income.

In coming Substack posts, I will be showing that the Blue states did not just happen to grow faster – their faster growth owed much to Democratic policies nationally, which heavily favored Blue state economies and the policies of Blue states’ governments, including much greater support for education and innovation.

Factor Three: Regional Realignment

The most important realignment in America has been regional – the reconstitution of both Democrats and Republicans as regional parties.3 I will have much more to say about this in subsequent posts, but here is an introduction. I will define “Red states” as those whose state governments have predominantly been led by Republicans since 2010, and “Blue states” as those predominantly led by Democrats since 2010. (Purple states are just 13 percent of Congress, and both parties have split those seats throughout the period. Therefore, for today we’ll just look at Blue states and Red states.)

The next chart traces that regional consolidation, marked at the beginning of each of the last five presidents’ first terms. In 1992, both parties' caucuses were nearly equally balanced by region – but by 2020, the regional distribution of the Republican Caucus nearly duplicated the distribution in 1928, the last presidential election before Democratic gains in the northern states during the New Deal. In other words, to the extent that you accept that before FDR, the Democratic Party was a regional entity dedicated to protecting its white Christian order, the same is true today for the Republican Party.

But the two panels above understate the extent and speed of regional sorting that has occurred because of the Voting Rights Act (VRA). Even after its provisions were weakened in Shelby County v. Holder, the VRA still ensures the existence of majority-minority (and therefore Democratic) districts in Red states. In 2020, there were only 19 Democrats representing majority-white districts in Red states, down from 92 in 1992! Meanwhile, the number of Blue state Republicans dwindled from 70 to 31. In 1992, Democrats represented more majority-white districts in Red States than in Blue states. And Red state representatives now constitute a greater share of the Republican Caucus than Confederate state representatives constituted of the Democratic Caucus about a century ago at the height of the Jim Crow era.

Here is another dramatic visualization depicting the regional sorting of white-majority districts starting in 1992, when Democratic districts solidly trailed Republican ones in income.4 Reading from the left, we can see that nearly all of the seats Democrats held in 1992 in Blue states, they held in 2020 as well; only a few switched to being Republican (the right side of the chart). And then Democrats picked up most of the seats Republicans had held in Blue states. The reverse is true for Republicans. Thus, to the extent that either party holds seats that it didn’t in 1992, Democrats hold them in Blue states and Republicans hold them in Red states.

And, again, a big driver of that regional realignment has been the increasing political power of the white Christian nationalist project. White Evangelical voters, and more importantly well resourced and heavily engaged white Evangelical churches, are concentrated in the Red states. This chart shows how much more concentrated white Evangelical voters are in Red states. (The yellow bars on the right represent the top quintile of districts by white Evangelical population.)

Demography or Geography?

At this point, you might still think that the regional realignment flows naturally from demographic realignment – that the Democratic Party has been “abandoning” lower income, less educated rural voters in favor of higher income, better educated urban voters, and so of course they will be representing more districts in Blue states, since Blue states are substantially higher income, better educated, and urban.

Moreover, it can be difficult to acknowledge the extent to which our values and ideals have been shaped by our circumstances. If you are reading this, you are likely to be a member of a thriving, educated political class. Many of us in that category are more ready to believe a story that attributes our differences to whether we went to college or not, and are loath to believe that the places we grew up or live now exert any influence on our values or partisanship. As a class, we tend to be committed to the idea that we are each the captains of our own ships, and that the values we have are wholly of our own making – that we would be the same people with the same convictions regardless of the communities we live in or grew up in.

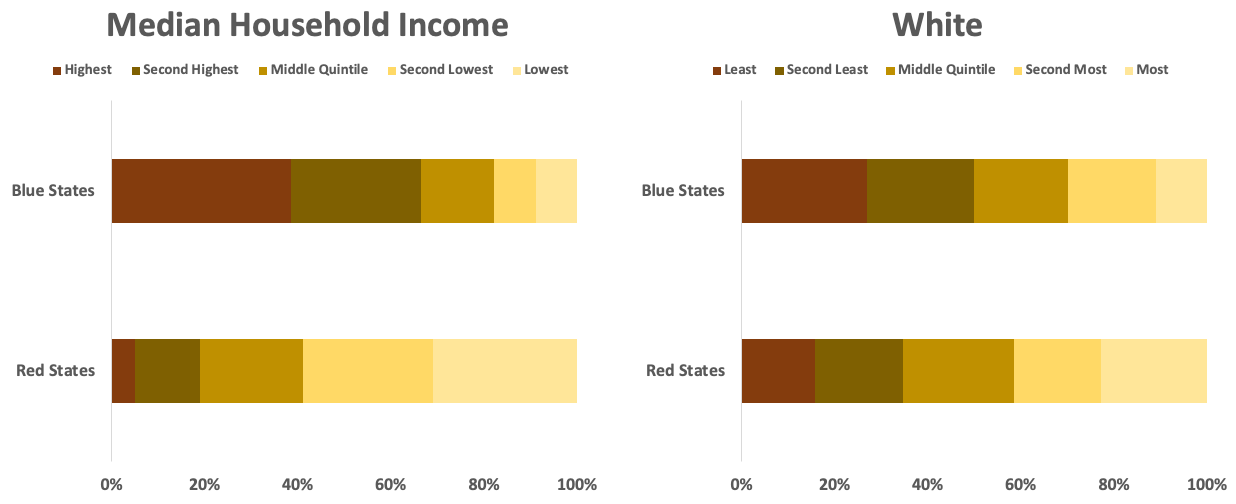

If nothing else, the next set of charts should help convince you that, in fact, the historical, cultural, economic and other influences that have separated the Blue and Red regions since the founding continue to do so now. Each chart takes a single variable – income, education, white, white Evangelical, and urbanicity5 – and shows that whatever the quintile for income, education, white or white Evangelical, or category of urbanicity, Democrats hold substantially more of the seats with that characteristic in Blue states than they do in Red states. This tight correlation of all the factors means that if you pick any one of them, it will seem that that factor could plausibly “explain” why the congressional district is more or less Democratic. But this visualization should underscore that partisanship is associated with the ways those factors combine. To do otherwise is like trying to explain human biology by explaining each body part separately.

(How to read: Democrats hold 94 percent of the most educated quintile in Blue states, but only 42 percent of such seats in Red states.6)

Notice that in Blue states, Democrats hold 64 percent of the districts in the educated quintile, 73 percent of the districts in the lowest income quintile, and 34 percent in the most rural districts. In other words, if representing the lowest education, lowest income districts amounts to representing the “working class,” that is very much the case for Democrats in Blue states.

For those of you who still wonder whether something else is going on, let’s look at the partisan choices of white voters in Blue and Red states. The following leverages 56,000 interviews in the Nationscape survey database7 to compare presidential voting across all the usual demographic variables. (Please see important methodological footnote here:8)

Let’s begin with something we take for granted without thinking – the meaning of party ID. Biden’s margin among Democrats is 6 points better in Blue states, among independents 33 points better in Blue states, and among Republicans 11 points better in Blue states.

The next chart breaks down the 2020 presidential vote of white voters in Blue and Red states by educational attainment. Here’s what we see:

Biden broke even with white non-college voters in Blue states, but lost them by 40 points if they were in Red states, a 40-point regional gap.

Biden won white college voters in Blue states by 19 points, but lost them by 9 points if they were in Red states, a 28-point regional gap.

The fact that Biden broke even with white non-college voters in Blue states while losing white college voters in Red states flies in the face of the established narrative on these demographics. Somehow, white non-college voters in states in which Blue trifecta legislatures have been expanding civil liberties and “burdening” their citizens with bigger government were more likely to vote for Biden and other Democrats than the brainwashed-to-be-woke college graduates who were confronted by Red state trifecta legislatures curtailing civil liberties and shrinking government services.

The regional difference holds up even when you subtract white Evangelicals from the picture. The regional gap remains high for white non-college – 34 points (8 + 26) – but remains 28 points for white college (33 - 5). But sit with this: Biden won white non-college voters in Blue states who were not Evangelical by 8 points – a bit more than the 5 points by which he white college, non-Evangelical voters in Red states.

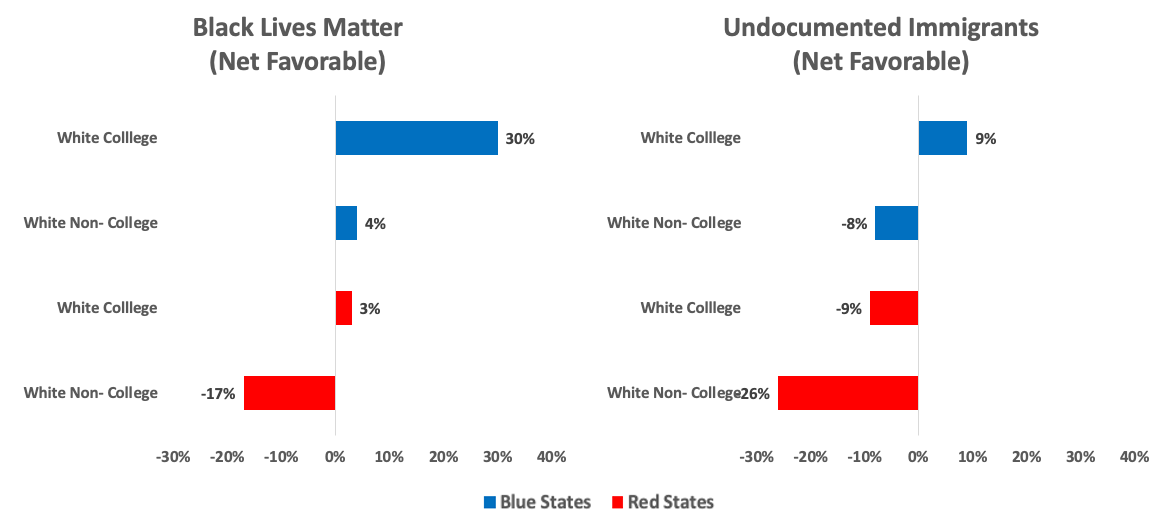

The next chart shows that those regional partisan differences reflect regional “cultural” differences as well, albeit usually to a smaller extent. Here are two hot button issues – Black Lives Matter and undocumented immigrants. As the conventional narrative would have you believe, white college voters have a favorable view of both. But, as with partisanship, regional variation is more consequential. The regional gap is huge – 27 points (about the same as the regional partisanship gap) for Black Lives Matter, and 18 points for undocumented immigrants (less than the regional partisanship gap). But the big news is that, as with partisanship, white non-college voters in Blue states are as socially liberal as white college voters are in Red states.

So, to recap, voters in every frequently referenced demographic category – most notably education and race – are significantly more Democratic and more liberal in the Blue states than the Red states. On top of that, the characteristics that are more Democratic or Republican are more common to Blue states and Red states respectively, as these sets of charts show. (In other words, Democrats do better with college educated voters and there are more college educated voters in Blue states.) The more Democratic characteristic is on the left side of each bar and the most Republican on the right side of the bar.

Conclusion

There are two broad ways of understanding why Democrats now represent more higher-income, higher-education districts than Republicans. The first is to do a straightforward tally to compare the average for a particular demographic category for the districts represented by Democrats and Republicans. Education, income and race are the most common categories to look at. The result is usually that, surprisingly, Democrats and not Republicans now represent the higher-end districts. So far, those conducting the analyses, and pundits commenting on the findings, proclaim (with no rigorous evidence because this idea is now so truthy) that we are seeing this reversal because the social liberalism of higher-educated, higher-income voters is out of step with the values of lower-educated, lower-income voters.

Unfortunately, these takes miss the most important part of the story – that the parties have again become the agents of their separate regions to Congress. To be clear, as you have seen, I don’t mean urban/rural sorting; I mean a regional shift. Democrats represent higher-income, higher-education districts now in large part because of how wide the spread between high/low districts in Blue/Red America has become. Blue states are richer and more educated than Red states, and getting more so. And there continues to be much more underpinning the differences than “social values” – one economy remains rooted in extractive industries, and the other in tech, communications, finance, and a globalized world. Neither Blue America nor Red America is free of their historical, institutional, and cultural inheritances.

Although the importance of the overwhelming regional differences should seem obvious, I think it has been very difficult for people to accept for two reasons. The first is that we like to think of America as one united nation – but looking at our regional divides this way makes it painfully clear that even after 250 years, America has still not realized e pluribus unum.

As we’ve seen, in the 21st Century we are again as polarIzed by party as we were until the New Deal. In the last three elections, Obama, Clinton and Biden won Blue America by nearly two dozen points, while Romney and Trump carried Red America by a dozen or more points.9

To be clear, this is not a deterministic argument – and I hope you can read this without falling back into an either-or mindset that says our political futures must be defined either by pure demographic destiny or pure free will. It is a plea to acknowledge a more complicated politics than can be seen through the pinhole polling provides us, and to understand that whether ours will be a future characterized by ethnonational fascism is neither as easy as messaging to moderates, nor as impossible as turning back impersonal tides that will wash us away or not. It will be a product of our own choices now – choices that might seem too costly until we fully accept the actual demons and dangers that make those choices necessary.

See The Atlantic article “How Working-Class White Voters Became the GOP’s Foundation” by Ron Brownstein, “Understanding the Partisan Divide: How Demographics and Policy Views Shape Party Coalitions” by Oscar Pocasangre, Lee Drutman, “Polarization of the Rich: The New Democratic Allegiance of Affluent Americans and the Politics of Redistribution” by Sam Zacher, “Donald Trump and the Democratic Shift among College-Educated Suburban White Voters” by Brian F. Schaffner and Kaitlyn Gaus, and “Upending the New Deal Regulatory Regime: Democratic Party Position Change on Financial Regulation”, by Richard Barton.

This analysis was based on creating a crosswalk between the 2002 and 2010 lines.

Blue States (California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington), Red States (Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, West Virginia, Wyoming), Purple States (Michigan, Nevada, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Wisconsin)

This is based on the process of cross walking districts across redistricting rounds. Ninety-four percent of today’s districts can be traced back to the similar boundaries in 1992 districts.

Based on CityLab classifications.

Note that these are still national quintiles, not the quintile recalculated for each set of states.

Thanks to Gretchen Pfau at Lake Research for the Nationscape analysis.

Important Methodological Note: First, as regular readers know, I am quite skeptical of the precision we accept from the surveys we use to understand the electorate, and that in particular, I think the extent to which educational attainment has become the go to variable is clouding rather than clarifying our understanding of political outcomes. My point in using educational attainment here is to show how dramatically adding region or religion upends what we think we know is “true” about those with or without degrees. So, I am not now arguing for a better way to look at college education; I am trying to show that although educational attainment does matter independent of other correlated factors, slicing the electorate by demographic categories collapses once additional information is added.

Second, nearly all serious academic work about the 2020 presidential elections relies on one or more of these three sources: American National Election Studies (ANES), Cooperative Election Study, (CES, formally CCES) and the Nationscape data set by the Democracy Fund Voter Study Group. In this post I am using Nationscape data because of its sample size and because of the availability of responses to items not asked on the others. That said, to the extent I could, I checked the results in this post against ANES and CES. Not surprisingly, all three do not line up perfectly. I say, “not surprisingly” because of the somewhat different survey and weighting methodology each employs.

For the results in this post, the most important difference between Nationscape and the other two is that the other two show Biden losing white non-college voters in Blue states. Nonetheless, while CES has Biden losing white non-college voters in Blue states by 8 points, CES has him losing white college in Red states by 7 points - thus leaving intact the essence of the point that there is not much difference in the partisanship of white non-college voters in Blue states and white college voters in Red states.

Election years without bars indicate the winner received a majority in both regions, or, in a few cases, lost one region by less than 5 points. For 72 years, from 1928 until 2000, presidents winning a majority of the votes in both regions was the norm (in those 18 elections, the regions were divided just three times, and then by relatively small margins). But in the 15 elections before that, the regions were divided 13 times. Indeed, a striking paradox of 21st Century elections is that the popular vote in every one of them was closer than the average for the 39 presidential elections since the Civil War, and that three of them were among the ten closest – yet all were sectional landslides.

Thanks, Laura

I agree strongly that we are not the products of individual decisions. We are extremely influenced by the politics of our parents and where we grew up. As for me and my two siblings, it is no accident that we have always been left leaning Democrats because our parents and grandparents were helped by the New Deal and the GI Bill and because we grew up in working class neighborhoods in Brooklyn, New York and Jersey City, New Jersey.