More Than the Weekend: Unions, the Past and the Future of Democracy

WIthout strong unions, “democratic capitalism” is an oxymoron.

Note: I have a new article out in The Atlantic today explaining why at the same time that autoworkers, screenwriters, actors, and UPS drivers are making big gains, and public support for unions is at a half-century high, Amazon, Starbucks and other companies haven’t even begun to negotiate with workers who have voted to unionize. As a complement to this, today I’m publishing an updated version of a “Weekend Reading” I wrote several years ago about why unions are not just beneficial to individual workers and workplaces, but why they are essential to shared prosperity and the functioning of a healthy democratic society.

Suddenly, America is paying more attention to the vital concerns of working people than it has in generations – the quality of manufacturing jobs in the new green economy, the increasing precarity of work generally, and the threats from AI specifically. Unacknowledged, but hiding in plain sight, is the reality that working people themselves are the reason for this shift in our national conversation. In union, working people have been striking to get their due for a better life for themselves and their families – demanding that we pay as much attention to those who work as we do to those who reap the rewards, and as much attention to those who owe as we do to those who own.

This post is not only about the better lives working people in unions claim for themselves; that dynamic is broadly understood, as reflected in the overwhelming (and usually bipartisan) public support for unions. Rather, this post is about why all of us have a stake in the resurgence of the labor movement more generally, because all of us are better off when working people are able to exercise collective power through unions.

Greater rates of union representation not only reduce economic inequality by ensuring that working people are rightly compensated for their efforts; greater rates of union representation also reduce political inequality, the cancer ravaging America today. Self-government requires a reasonably equal distribution of political power. And to achieve that in a capitalist system, robust collective action is required to counter the inevitably outsized political power claimed by concentrated wealth. In all times and places, the stronger unions have been – and with them, the practice of collective action more generally – the closer societies have come to the ideals of the Declaration of Independence.

In his 1944 State of the Union, Franklin Roosevelt recognized this clearly:

We have come to a clear realization of the fact that true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence. "Necessitous men are not free men." People who are hungry and out of a job are the stuff of which dictatorships are made.

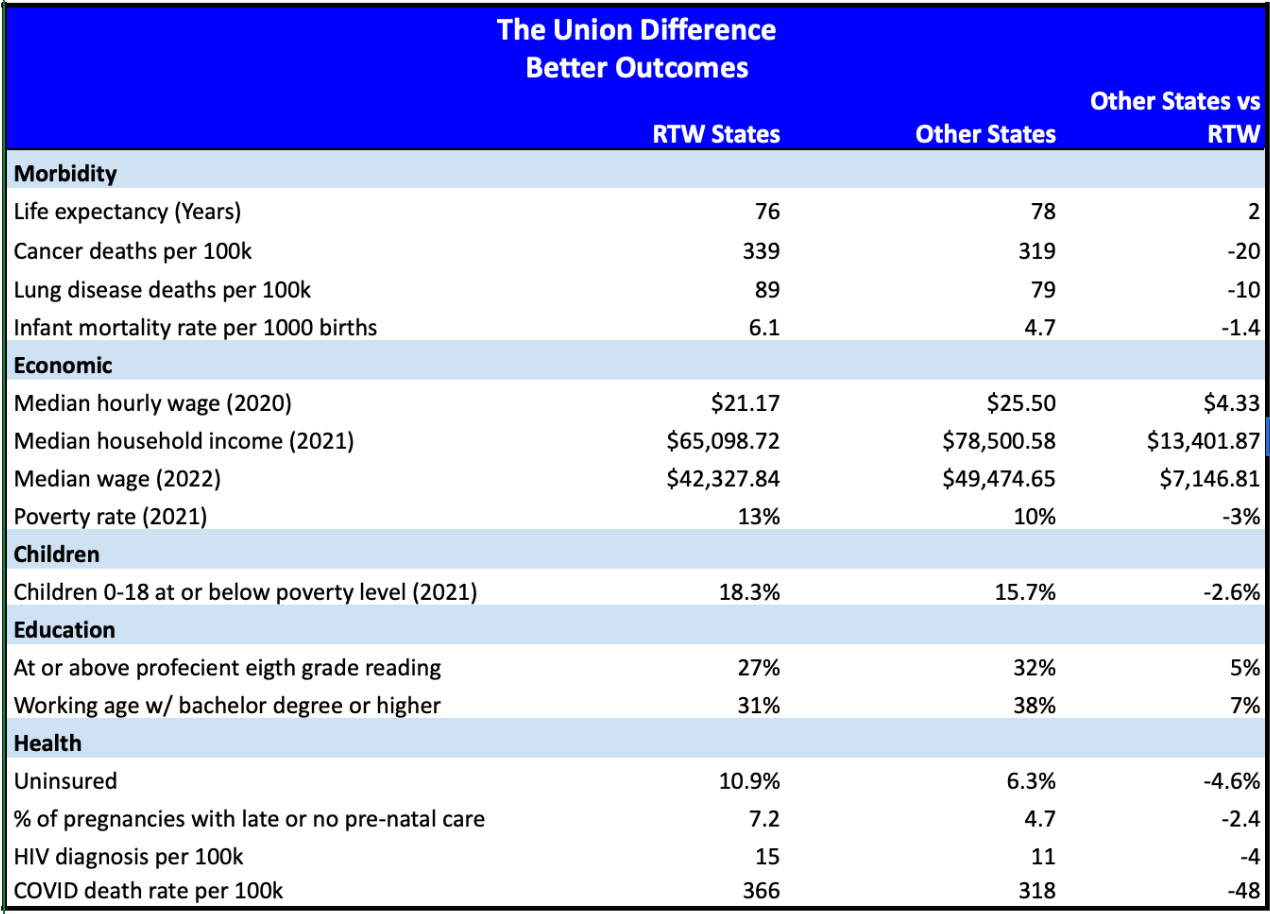

Unions, and the habits of collective action they instill, strengthen democracy, promote racial and gender tolerance, resist authoritarianism, and increase support for a more generous state. What’s more, depending on whether they live in a state with “right to work” laws that disempower unions, Americans are living in two different realities – one with the benefits of unions and robust democracy, and one without. Those living in states with so-called “right to work” laws, which make it nearly impossible now to organize collectively, can expect to live two fewer years and earn more than $10,000 per year less.

A substantial body of evidence and academic literature supports all of these points, but the public rarely if ever hears about it. Because I think it’s important to make this case in a comprehensive way, this post will be longer than usual (even for me), but hopefully also skimmable and useful.

Table of Contents:

How Unions Strengthen Democracy

How Unions Give Working People Political Voice

Why Unions Are the Bulwark Against MAGA Fascism and Authoritarianism

How Unions Reduce Economic Inequality

How Unions Create Better Working Conditions

Part I: How Unions Strengthen Democracy

Healthy democracies require more than free and fair elections; they require citizens who are practiced in the habits of democracy. The benefits of unions to democracy accrue from allowing working people to organize themselves collectively and democratically to act on their own behalf. It is the practice of acting democratically and collectively to negotiate contracts and set working conditions that produces more tolerant, effective citizens, and more responsive and accountable government.

Union members practice a form of democracy that has all but disappeared elsewhere in America. Unions are themselves one of the most democratic institutions in the country, as this Center for American Progress report details.1 With more than 10,000 local unions in the country, there are about 5 million working people who have served as elected stewards or more.

Greater electoral participation

In the recently published Right to Work or Right to Vote? Labor Policy and American Democracy, Paul Frymer, Jacob M. Grumbach, and Charlotte Hill conclude that anti-union “right-to-work laws had a substantial negative effect on state level electoral democracy in recent decades, even net of Republican control of government.” (Emphasis added.) That’s consistent with many other earlier studies, as well as the membership files of the AFL-CIO and other unions, which show that union members are more likely to be registered and to vote compared to those not in a union. Importantly, the same is true for those living in areas with higher union density, as Benjamin Radcliff and Patricia Davis find that “labor organization is one of the principal determinants of cross-national and domestic rates of electoral participation.”

Greater political engagement

This paper by Roland Zullo finds that higher union density is positively associated with many forms of political civic engagement beyond voting. In counties with higher union density, both union members and non union members were more likely to sign a petition, attend a political rally or meeting, participate in a protest, attend a public meeting, or be involved with a political group.

More responsive congressional representation

This recent paper from Michael Becher and Daniel Stegmueller uses an impressive array of survey data and union membership data to show that the presence of stronger unions within U.S. House districts leads to more policy responsiveness for lower-income Americans (and less responsiveness for higher-income Americans), especially on economic issues.

Resistance to system justification

John Jost’s Theory of System Justification provides a powerful explanation of why oppressed people rarely rebel. Relevant here is the theory’s logic, borne out in research, that willingness to protest is much less a function of the extent of oppression than of beliefs about group efficacy. Jost writes: “Collective action is more likely when people have shared interests, feel relatively deprived, are angry, believe they can make a difference and strongly identify with relevant social groups.”

This paper by Greg Lyon and Brian Shaffner documents how unions increase protest activity among non-members through social ties – especially relevant for thinking about how unions have seeded and supported recent protests.

Advancing racial solidarity and civil rights

Although very far from perfect, and especially in its origins often an accomplice to segregation and racism, the union movement has also been an essential partner in dismantling elements of systemic racism – thereby advancing multi-racial democracy.

Unions increase racial tolerance among white workers:

Jacob Grumbach and Paul Frymer report that being a union member makes white workers more racially tolerant. Using cross-sectional data to compare attitudes of demographically similar white union workers with non-union workers and panel data, they estimate the effect of joining a union on change in racial attitudes among white workers. They found little difference in the effect between professional and blue collar unions, and found that the effect is the same in right-to-work states (suggesting that the effect is not due to racial liberals selecting into unions). The effect is a byproduct of what it means to be in a union – solidarity. In other words, belonging to a union inoculates members against racialized dog whistling based on opposition to federal programs.

Unions were an essential partner in the civil rights movement:

As Martin Luther King said in 1962, “The coalition that can have the greatest impact in the struggle for human dignity here in America is that of the Negro and the forces of labor, because their fortunes are so closely intertwined.”

In Racial Realignment: The Transformation of American Liberalism, 1932-1965, Eric Schickler recovers the importance of the partnership between the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) and the Civil Rights movement. The solid segregationist South initially supported most of the early New Deal’s pro-worker legislation, including the Wagner Act (albeit with the price of carve-outs for agricultural and domestic workers). However, once the CIO began multiracial organizing efforts in the South, Southern Democrats turned on labor. Over the next several decades, the Civil Rights movement and the CIO made common cause against the Southern wing inside the Democratic Party, succeeding in adopting a Civil Rights plank at the 1948 Democratic Convention that triggered Strom Thurmond’s third party candidacy that year, which carried Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi and South Carolina. Speakers at the March on Washington included A. Philip Randolph and Walter Reuther. Also see Paul Frymer’s Black and Blue: African Americans, the Labor Movement and the Decline of the Democratic Party.2

Part II: How Unions Give Working People Political Voice

As works like When Movements Anchor Parties show, for movements to sustain success, they must have a seat at one or the other party’s table rather than simply advocate for their positions in a non-partisan, ad hoc way. Movements that don’t – for example the abolitionists, populists, and anti-war movements – do frequently achieve some of their specific policy demands, but then see those gains erode rapidly as their mobilization disbands. On the other hand, we can clearly see how much more the Christian Right has been able to achieve through intra-party dominance rather than bringing its demands forward in a non-partisan fashion.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there was a strong worker backlash to rapacious capitalists throughout the industrializing world. At one extreme, the result was the Bolshevik Revolution in the Soviet Union. Most of Western Europe struck a balance with the emergence of formal labor or socialist parties.3 At the other extreme, in the United States, labor could do no better than being just one of many competing interests in the Democratic Party coalition.

Beginning in the 1970’s, in large part to overcome congressional and judicial opposition to agenda items like investor friendly trade agreements, segments of the business community set out to dominate the Democratic as well as Republican Parties. This accelerated the erosion of the labor movement’s power within the Democratic coalition. Thus, working people and their unions have a complicated relationship with the Democratic Party. On the one hand, it was New Deal Democrats who enacted the landmark Wagner Act and the Fair Labor Standards Act, the legal foundation of the rights working people can still claim. On the other hand, since 1976, the Carter, Clinton, and Obama administrations have pursued “free trade” and deregulatory policies and failed to make labor law reform a priority, allowing continuing erosion of working people’s ability to act collectively.

Meanwhile, there is nothing complicated about the foundational alliance between the Republican Party and employers. The Republican Party has not only voted filibustered every major attempt to enhance workers’ rights; they were instrumental in every action to roll back workers’ rights, from the Taft Hartley law in the 1950’s to today – preventing even a consideration of raising the federal minimum wage, which hasn’t been adjusted since 2009.

The reason for providing this context is to underscore that in what follows, when I use supporting Democrats as a positive metric, it is because in our current system, only through the labor movement’s power within the Democratic coalition can the interests of working people be expressed politically.

Union members are more likely to vote for Democrats

Numerous studies document the connection between union strength and Democratic and progressive political impacts:

Union members vote more Democratic than their neighbors. Frymer and Grumbach estimate that in the 21st Century, white union members were between 8 and 14 points more Democratic than non-union members on a 100-point scale.

FiveThirtyEight: Big 2008 and 2012 Impact. Additionally, Nate Silver and Harry Enten wrote about how consequential that gap was in the 2008 and 2012 elections, accounting for about 1.7 points of Obama’s margin in both. After controlling for other demographics, they found that union membership increased the likelihood of voting for Obama, and that if union households sat out, his 2008 victory margin would have been decreased by 75%. Thus, it is not surprising that fewer union members = fewer Democrats.

Union members are key Democratic campaign contributors

Through their PACs, union members had long provided foundational resources for Democratic candidates. Those resources obviously helped Democrats running against Republicans. Crucially, but less obvious, this was also an important way of ensuring that within the Democratic Party, working families could be on a level playing field with business interests. But, especially after Citizens United, when the flow of money into campaign coffers exploded, working people could not keep up.

Both the OpenSecrets and FollowTheMoney websites track union giving. For example, in 2020, contributions to candidates had increased by $2.6 billion compared to 2008, and by $1.3 billion for Democratic candidates. Yet contributions from labor increased by only $1 million.4

These trends can be seen clearly in the next graph, which shows that the total contributions from unions to Democrats in presidential years since 1992 (bars) has been fairly steady, while those contributions made up a dramatically dwindling share of contributions to Democrats as time went on.

That was the pattern at the state level as well, and has been a significant factor in the well documented Republican state legislative advantage post-Citizens United.5 According to this study:

Citizens United boosted corporate power much more than union power in states affected by the ruling. In the two election cycles before Citizens United, only a minority (44%) of all corporate and union independent expenditures were made by corporations. In the three election cycles after the year of the ruling, the majority (68%) of independent expenditures from corporations and unions came from corporate sources.6 [And that does not factor in large sums to dark money groups.]7

Part III: Why Unions Are the Bulwark Against MAGA Fascism and Authoritarianism

Unions reduce authoritarian attitudes

This study in Nature showed that “Participatory practices at work change attitudes and behavior toward societal authority and justice.” Specifically, they found that “participatory meetings led workers to be less authoritarian and more critical about societal authority and justice, and to be more willing to participate in political, social, and familial decision-making.” It confirms earlier research here, here, here, here, here, here, here and here that unions fundamentally change members' understanding of and expectations for the relations of power between themselves and their employers.

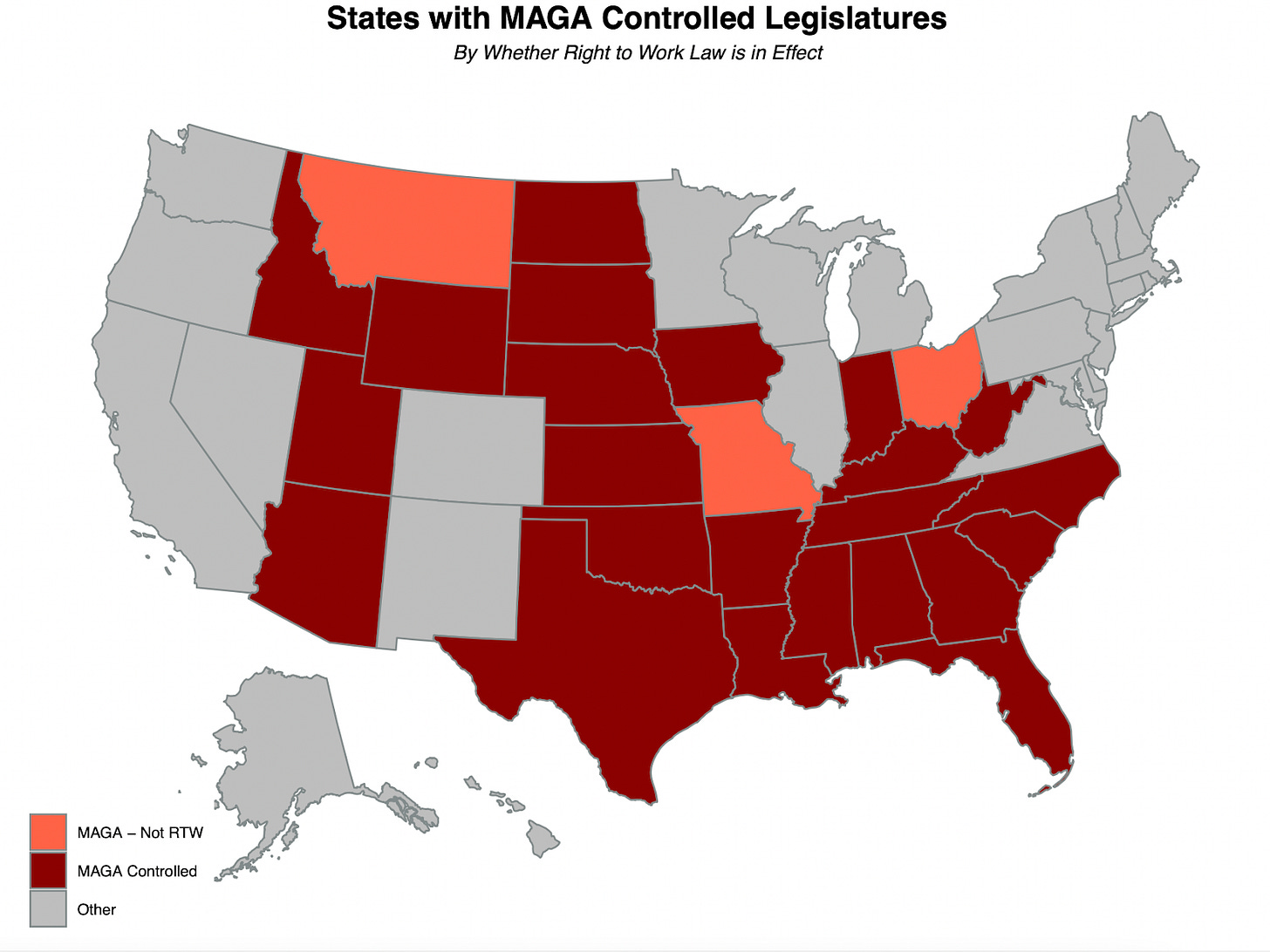

Thus, it should not be surprising that since 2008, MAGA Republicans have been able to fully control the legislatures in 24 of the 26 “right to work” states. In the only two states they haven’t been able to, Nevada and Virginia, MAGA has been thwarted by local union movements that have succeeded despite the barriers created by right to work laws. As this map illustrates, Missouri, Montana, and Ohio are the only non-right to work states in which MAGA has been successful.8

Right to Work laws hurt Democrats and democracy

Right to Work Costs Democrats 3.5 Points.

In this 2018 study, Alexander Hertel Fernandez & peers carefully examined the impact of the passage of right to work laws and concluded that Democrats pay an average of a 3.5 point penalty after passage. They attribute that drop to lower union density, less political activism, and collateral impacts on family and neighbors. Data for Progress takes a different approach, and finds the same result. Instead of looking at RTW, they create a time series relating union density to congressional vote for each of the 50 states. As union density in a state declines, so does the Democratic vote share. The slope is much steeper after 1990.

Right to Work Broke the Blue Wall

In 2008, Michigan (+16.7 Obama), Minnesota (+10.5), and Wisconsin (+13.9) were considered key parts of the Blue Wall. By 2020, the bottom had fallen out in Michigan and Wisconsin—but not in Minnesota.

The nearly universal conventional wisdom is that the Blue Wall crumbled because education polarization is driving voters without a college degree away from Democrats. But, as you can see, those without a college degree constitute nearly as great a share CVAP in Minnesota as they do in Michigan or Wisconsin. All three states are substantially less diverse than the country as a whole, and while Minnesota is a bit more diverse than Wisconsin, it's less diverse than Michigan.

The difference in political trajectories between Minnesota and its neighbors cannot be explained by demographics – but much of it can be explained by the well-financed right-wing political projects in Michigan and Wisconsin. In 2010, Scott Walker and Rick Snyder were elected governors, and Republicans won substantial majorities in those state legislatures. Just across the border from Wisconsin, Mark Dayton won the slimmest of victories (just under 9,000 votes) to become governor of Minnesota. With their trifectas, both Walker and Snyder acted aggressively to curtail democracy and decimate unions, while Dayton did not.

None of this was accidental or due to a sea change in voters’ attitudes. Billionaires in Wisconsin (Bradley) and Michigan (DeVos) organized and financed the takeovers of those states’ governments. In The Fall of Wisconsin: The Conservative Conquest of a Progressive Bastion and the Future of American Politics, Dan Kauffman “traces the ways Wisconsin’s century-old progressive legacy has been dismantled in virtually every area: labor rights, environmental protection, voting rights, government transparency.”

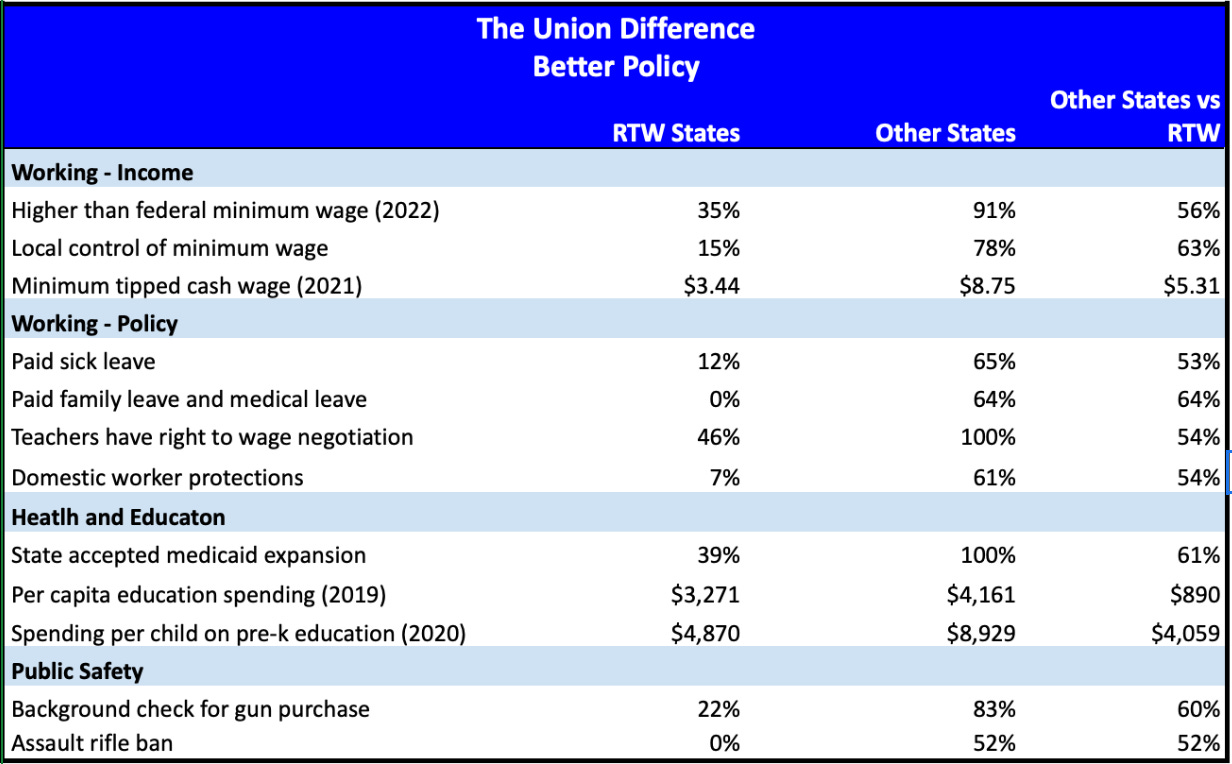

Unions Spread Prosperity Beyond Their Membership

There are stark differences between life in the 28 “right to work” states and the other 22 states. In fact, we can imagine America as two economies – one in which a low-wage, extractive labor model prevails (right to work states), and another where the rights of working people are recognized, if insufficiently (the rest of the states). In the “right to work” economy, you will see not only lower wages for the same work; you will also see a less healthy region on a myriad of basic indicators, from life expectancy and maternal mortality to standards of living and educational attainment.

Here is some data showing “the union difference” between these two economies – how different life is for those living in right to work states compared to those living in the rest of the United States. While most efforts to quantify regional differences quantify the number of states that have certain policies or outcomes, in this post, we will look at the much more meaningful average or percentage of people in those states who experience those policies or outcomes. In other words, we can see clearly how different life is for people who live in states with anti-collective action laws and policies that keep wages low and make quality of life worse.

To be clear, I am not arguing that the better conditions in the latter region than the former is entirely due to unions. Rather, greater effective collective action is both the cause and effect of a healthy society.

Working people are more than twice as likely to be represented by a union in the rest of the country as they are in right to work states. Indeed, the corporate-government coalition against working people has been so successful in those states that only one in twenty five private sector workers are represented by a union – fewer than the era before the Wagner Act, when working people had to contend with the private armies deployed by the railroads, mine owners, and manufacturers.

Better Life Outcomes

As you can see, those living in right to work states have far worse life outcomes than in the rest of the country – whether it’s shorter life expectancy (2 years), higher infant and maternal mortality rates, greater rates of firearm deaths, or lower wages and incomes.9

Better Policy Choices

Those worse life outcomes in right to work states are the direct results of the passage of regressive policies (or rejection of progressive policies) by the state governments. The social safety net is far stingier and basic freedoms are far more limited.

More Democracy

In short, those consistently poorer outcomes in right to work states are both cause and consequence of those states’ across the board restrictions on collective action. It adds up to substantially less democracy by any standard.

Part IV: How Unions Reduce Economic Inequality

Unfortunately, to the extent that severe “inequality” is acknowledged as a problem, it seen as troubling, but inadvertent – and certainly not intended. It is completely uncontroversial to decry how unfair it is that a few have so much wealth, income, or opportunity, while the many have so little. But we never talk about inequality in terms of power – even though all the other severe inequalities are the downstream results of inequalities in power.

Unions reduce economic inequality because they also reduce the massive inequality of power between working people and corporations. We don’t often think about the ways in which corporations are wielding “collective power,” but that’s precisely what our capitalist system encourages.10 Consider all the ways that if you have money, you can easily accrue greater wealth and power by acting collectively in the corporate framework – indeed, “today the effective taxes on corporations and billionaires are at the lowest levels since the 1920s,”11 and profits are now taxed less than work.12 Moreover, when you do so, you are all but shielded from any liability for the consequences of actions taken by the collective.

Against the corporation, a working person without a union has almost no power. It’s obviously absurd to say, as many do, that an employee is as free to quit a company as the employer is to fire her. Nearly every corporation has the assets to make do for quite a while even if the employee isn’t easily replaced. On the other hand, most working people do not have the savings to make do for very long without a job at all.

Progressive movements tend to emphasize the need for redistributive policies through greater taxation of the rich and corporations, with the proceeds to go to transfer payments or public goods. However, working people do not seek the government to lift them up, but to give them a level playing field in the workplace so they, collectively, can lift themselves up. Consider, for example, that SNAP, the largest federal transfer program after Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, is $122 billion per year, while economists estimate that belonging to unions raises members’ compensation by more than $150 billion.

Unions play an indispensable role in creating and reinforcing community norms as to the need for greater economic equality – which is expressed in federal and state policy, as these studies make clear here, here, here, here, and here.

From Robber Barons to Shared Prosperity…and Back to Plutocracy

This chart from the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) is one of many that show the connection between corporate success, weakened unions, and the increasing share of income going to the top one percent. EPI’s analysis on “Unions, inequality, and faltering middle-class wages” provides an excellent overview of much of the literature on this subject.

In “Unions and Inequality Over the Twentieth Century: New Evidence From Survey Data,” Farber, Herbst, Kuziemko, and Naidu show how the strength of unions and collective bargaining in the United States after World War II disproportionately benefited low wage workers and workers of color. It remains the gold standard analysis so far of unions and economic outcomes over the long run in the 20th century.

This chart from that article begins the time series earlier than others, in 1917. It shows how the adoption of the Wagner Act in 1935 rapidly ameliorated inequality (the green and dark blue lines between 1937 and 1947).

Research has also taken several approaches to demonstrating the causal relationship between unions and economic equality. For example, this paper found that “the decline of organized labor explains a fifth to a third of the growth in inequality” from 1973 to 2007. Moreover, this paper shows how since the Taft-Hartley Act allowed states to pass right to work laws, those laws have increased local income inequality, underscoring the causal relationship.

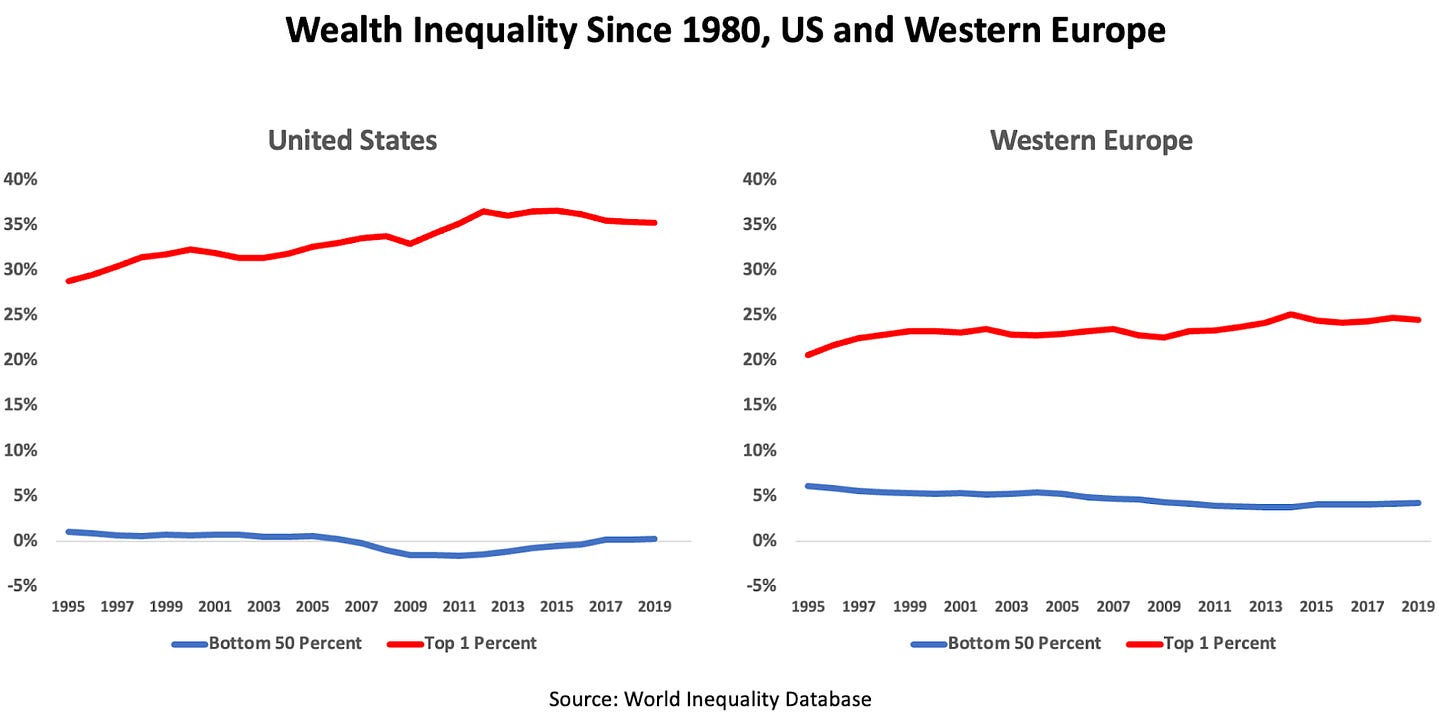

Shared Prosperity: From World Leader to Laggard

It’s commonly believed that the trends in income inequality we’ve seen in the United States reflect worldwide trends due to greater globalization. But, as the following graphs show, that is far from the case.

Let’s compare the experience in the United States with Western Europe, where labor unions have not suffered the same erosion. In 1980, when comparable data first became available, the shares of pre-tax national income in the US and Western Europe held by the bottom 50 percent were roughly comparable, as was the share held by the top 1 percent in both. But while these shares have changed modestly in Western Europe, in the United States, the share held by the top 1 percent has radically increased while the share held by the bottom 50 percent has radically decreased. (And, remember, this is pre-tax income – which means that, given the greater social benefits in Western Europe, these graphs underestimate the trends.)

Indeed, as the next graph shows, while there has been some erosion in the relative shares in Western Europe, in the United States, the relationship is reversed – with the top 1 percent holding 5 percent more pre-tax income than the bottom 50 percent, compared to 1980, when the bottom 50 percent held 10 percent more.

Not surprisingly, the top 1 percent have held a greater share of wealth than the bottom 50 percent throughout the period in both the United States and Western Europe. But, as the next two graphs show, the gap between the two wealth groups was smaller in Western Europe than in the United States in 1995, when comparable data became available, and has widened more since then in the United States. Significantly, throughout the last nearly thirty years, the bottom half of the wealth distribution in the United States hasn’t had any growth in wealth, and was often in debt.

This report from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) documents the positive effects of unions across the developed world.

Mitigating the Racial and Gender Wage and Wealth Gaps

In 2021, the Center for American Progress released data showing how unions help close the racial wealth gap, comparing data on household wealth from 2010-2019. While union membership had a wealth premium for households of all races, with the union to non-union ratio being 224.7% overall, for Black households it was an astounding 349.7%, and for Hispanic households it was 517.7%. This was far higher than the premium that union membership afforded white household wealth, with the ratio of union to nonunion for whites being 180.2%. A more recent analysis found the same pattern holds among non-college households: the wealth ratio between union and nonunion households was 385% overall, 434% for Black households, 536% for Hispanic households, and 334% for White households.

The Direct Economic Benefits of Union Membership

The labor movement enables working people to claim a greater share of the wealth they create. Studies show that union workers make about $150 billion more a year than non-union workers in wages alone, controlling for industry, occupation, education, and experience. And union workers are much more likely to have health, pension, and leave benefits than non-union workers, and those benefits are much more substantial than those non-union workers who have them at all. Among the benefits:

Economic mobility. Research in the last decade has shown that unions increase economic mobility for low-income children, and that just the presence of unions in an area increases the mobility of all children for the geographic region. Much of the lack of economic opportunity in recent years has disproportionately been felt by workers without college degrees, but children of non-college-educated fathers earn 28% more if their father was in a labor union.

Wealth. This study found that, according to Federal Reserve data, the median wealth for union households is $270,000 – more than twice the wealth of the median nonunion household. A recent update to that study found that this effect is even more pronounced among non-college households; the median non-college union household has four times as much wealth as the median non-college nonunion household. The same study found that non-college union families are more likely to own a home, have a 401k, and have a pension than their nonunion peers, and that unions help close the wealth gap between college and non-college families.

Lifetime earnings. A recent paper by Zachary Parolin and Tom VanHeuvelen found that unionization throughout one’s career is associated with a $1.3 million mean increase in lifetime earnings, more than the average benefit from completing college. These gains occur despite earlier-than-average retirement for consistently unionized men, and increase with more years of union membership.

Part V: How Unions Create Better Working Conditions

Unions are frequently (and correctly) credited for winning fundamental improvements in working conditions that many of us now take for granted, like the 40-hour work week and the weekend. Often forgotten, though, is the crucial role unions continue to play in securing safe and fair conditions for workers today.

Here, we’ll look at how unions provide countervailing power for workers in modern tyrannical workplaces, allow workers to safely exercise their rights, and create states with more family friendly policies for all workers.

Workplace Tyranny

Elizabeth Anderson makes the point that “We are told that our choice is between free markets and state control, when most adults live their working lives under a third thing entirely: private government.”13 She asks us to:

Imagine a government that assigns almost everyone a superior whom they must obey. Although superiors give most inferiors a routine to follow, there is no rule of law. Orders may be arbitrary and can change at any time, without prior notice or opportunity to appeal. Superiors are unaccountable to those they order around. They are neither elected nor removable by their inferiors. Inferiors have no right to complain in court about how they are being treated, except in a few narrowly defined cases. They also have no right to be consulted about the orders they are given.14

Indeed, she calls (non-union) corporations “communist dictatorships” that not only govern our work lives, but also have:

… the legal authority to regulate workers’ off-hour lives as well—their political activities, speech, choice of sexual partner, use of recreational drugs, alcohol, smoking, and exercise. Because most employers exercise this off-hours authority irregularly, arbitrarily, and without warning, most workers are unaware of how sweeping it is.

Under the U.S. default of at-will employment, working people might be shocked to learn that they can be fired “for their off-hours Facebook postings, or for supporting a political candidate their boss opposes.”15

Anderson diagnoses this as “a kind of political hemiagnosia: like those patients who cannot perceive one-half of their bodies, a large class of libertarian-leaning thinkers and politicians, with considerable public following, cannot perceive half of the economy: they cannot perceive the half that takes place beyond the market, after the employment contract is accepted.16

Surprisingly, the recently published Tyranny Inc, suffers from no such political hemiagnosia.

This tyranny subjugates us not as citizens but as employees and consumers, members of the class of people who lack control over most of society’s productive and financial assets. It is the structural cause behind much of our daily anxiety: the fear that we are utterly dispensable at work, that we are one illness or other personal mishap away from a potential financial disaster. Yet even to speak of private, economic tyranny as tyranny challenges some of our society’s most fundamental assumptions. Tyranny, according to the prevailing view, is the threat posed to freedom by the machinery of the modern state: by presidents, prime ministers, lawmakers, judges, prosecutors, law enforcers, intelligence professionals, military officers, regulators, and myriad other elected and unelected officials. Tyranny, then, can only be a public, governmental thing.17

Unions Make for Safer, Healthier Workplaces

The labor movement was instrumental in the passage of the 1970 Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA), which requires employers to provide a safe workplace for their employees. The act also grants several important rights to workers:

the right to file a complaint and receive an OSHA inspection if there are unsafe conditions;

the right to walk around with an inspector during the inspection;

the right to get information about chemical exposures and injury and illness data; and

the right to exercise your health and safety rights without fear of retaliation – including, in some cases, the right to refuse to do unsafe work.

But all these rights are easier and safer to exercise if workers are in unions. Some OSHA rights, such as the ability to walk around with OSHA inspectors during an inspection, are reserved for the workers’ “designated representative,” which generally means the union representative. Others, such as the right to refuse to do unsafe work, are more difficult for non-union workers to exercise because OSHA language prohibiting employers from retaliating against workers for exercising their rights under the law is weak.

In addition, unions can provide workers with protections that OSHA doesn’t provide. OSHA, for example, doesn’t have standards that cover many hazards (such as heat, workplace violence, ergonomic hazards and most chemicals and infectious diseases), but such protections can be written into union contracts. Many unions have dedicated health and safety staff.

Finally, OSHA operates by establishing health and safety standards, and then enforcing those standards. The standard setting process is long and arduous, but it is open to robust public comment. While corporate America is able to throw many millions into fighting or weakening OSHA standards, unions are generally the only institutions that provide worker-oriented input into OSHA’s rule-making process.

Numerous studies have shown that union workplaces are safer than non-union workplaces. For example, this study released found that unionized nursing homes were associated with 6.8 percent lower worker COVID-19 infection rates (as well as 10.8 percent lower resident COVID-19 mortality rates).

CONCLUSION

After more than 40 years of bipartisan neoliberalism, we are in the midst of an increasingly acute crisis of economic pain, of hopelessness, and of the concentration of economic, political, and social power in the hands of a small group of staggeringly wealthy people – America’s own homegrown plutocrats. In this landscape of mistrust and powerlessness, voices of hate and division and outright con artists are able to offer themselves as solutions, often funded by the very people who don’t want a solution.

I hope that it will be clear that the barriers to enacting solutions to those problems exist for exactly the same reason that we have the problems in the first place – the staggering imbalance of power between those who rig the system on their behalf and those who suffer the consequences. It’s long past time we recover what was known generally when prosperity was more broadly shared - that a more just capitalist society requires strong countervailing power to constrain it. A strong government is necessary, but insufficient when the people rely only on that state and not on themselves, organized collectively. Without that, strong states are inevitably captured by the most powerful.

This landscape leads many people to decide there is no way to build a genuine pro-democracy majority, while all the while the path to revitalizing America lies right in front of them. Behind the Starbucks counter, in the Amazon warehouse, or at their favorite REI or Apple store, democracy itself is being reinvented – if only we give it a chance and protect it from our homegrown oligarchs and their political instruments who would strangle it in its infancy.

The labor movement – working people organizing their own institutions, speaking for themselves in their workplaces, in their union halls, in the public square and in the voting booth – is the foundation of democracy. It is time that this foundation was rebuilt, and rebuilt strong enough to support the vibrant, participatory 21st century democracy that America so desperately needs. But when faith in the political system fails, acquiescence turns to action as working people turn either to tyrants or to each other for hope. These are such times.

The study also shows how much more democratic decision making in unions is compared to corporations. In elections, union members each get one vote, while in corporations the default is one share, one vote. In addition, certain classes of shares denote more voting power for their owners. Union voting is done with a secret ballot, while corporate voting is public. Union members have a fairly equal opportunity to run for office, and fairly strong limits against incumbent officers advantaging certain candidates over others, while in corporations, incumbent directors enjoy a distinct advantage.

Frymer, Paul. Black and Blue (Princeton Studies in American Politics: Historical, International, and Comparative Perspectives). Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

See, for example, Daniel Ziblatt, The Conservative Dilemma.

These figures do not include independent spending where the trends were similar, but there isn't the same kind of apples to apples data available to compare.

Abdul-Razzak, Nour, Carlo Prato, and Stephane Wolton. 2016. “After Citizens United: How Outside Spending Shapes American Democracy.” Available at SSRN: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2823778.

Klumpp, Tilman, Hugo M. Mialon, and Michael A. Williams. 2016. “The Business of American Democracy: Citizens United, Independent Spending, and Elections.” The Journal of Law and Economics 59(1)

Gilens, Martin, Shawn Patterson, and Pavielle Haines. 2021. “Campaign Finance Regulations and Public Policy.” American Political Science Review 115(3): 1074–81.

Massoglia, Anna. 2020. “Dark Money” in Politics Skyrocketed in the Wake of Citizens United. OpenSecrets. https://www.opensecrets.org/news/2020/01/dark-money-10years-citizens-united/

Note that although Republicans currently have a trifecta in New Hampshire, it is not shown on the map because Sununu and the Republican legislature have not been towing the MAGA line.

Sources for charts in this post: (All data featured in charts is for most recent year available. Numbers in chart are weighted for population of the specified state group; for example, of the total population living in states with RTW laws, 18.3% of the children are in poverty.)

Minimum Wage: U.S. Department of Labor, NCSL

Abortion Bans: Kaiser Family Foundation, Guttmacher

Attacks on Abortion Rights: Elizabeth Nash, Guttmacher Institute, WER Research

Gun Laws: http://www.statefirearmlaws.org/resources

Death Penalty: https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/state-and-federal-info/state-by-state

ACA: Kaiser Family Foundation, WER Research

TANF: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Education Spending per capita: Urban.org, taxpolicycenter.org, Census.gov, WER Research

Union membership: BLS

Voting Laws: NCSL, Brennon Center; Cost of Voting: https://costofvotingindex.com/data

Cost of voting: https://costofvotingindex.com/

Grumbach Democracy Index: https://sites.google.com/view/jakegrumbach/state-democracy-index?authuser=0;

Poverty & Insured: Census

Life expectancy, Disease & Mortality: CDC, Kaiser Family Foundation

Reading proficiency: NCES; Degrees: Census.

Covid: NYT

Trust & social capital: JEC Social Capital Project

Minimum Wage: DOL,NCSL,

Union Density, Wages: BLS, EPI,BEA

Median HH Income: Census.

Other labor laws: Oxfam

Other: CDC.

I want to be clear that here I am talking about individuals acting collectively through corporations, not corporations acting collectively in the market. There have been times in American history when there have been effective limits on that, but vigorous antitrust enforcement has been all but non-existent until very recently. See, for example, Matt Stoller’s Goliath for that history.

Turchin, Peter. End Times (p. 206). Penguin Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Many wealthy corporations pay no taxes or almost no taxes on their profits, which they achieve by taking advantage of domestic tax breaks and loopholes, as well as hiding their profits in international tax havens. These corporations also receive massive public subsidies; block legislation that benefits workers (but hurts their profits); spend billions on lobbying Congress to pass pro-corporate laws; and spend billions more on electing pro-corporate candidates.

Anderson, Elizabeth. Private Government: 44 (The University Center for Human Values Series) (p. 6). Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

Anderson, Elizabeth. Private Government: 44 (The University Center for Human Values Series) (p. 37). Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

Anderson, Elizabeth. Private Government: 44 (The University Center for Human Values Series) (pp. 39-40). Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

Anderson, Elizabeth. Private Government: 44 (The University Center for Human Values Series) (pp. 57-58). Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

Ahmari, Sohrab. Tyranny, Inc. (pp. xx-xxi). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

I really enjoyed this article and will read it again. Of course, I want to know how we can get out of the mess we’re in, Thank you.

David Holzman's absolutely right that this is a great piece and I'm glad to see the Atlantic has Michael Podhorzer in, too. Now all we need is to bring every union member and every potential union member out to vote for Joe Biden, the most pro-Union President since FDR!