Poll-Washing Trump's Fascist Plans

What Voters Don't Know About "Mass Deportation" Can Hurt Us All

In the wake of the mass atrocities of the mid-20th century, George Orwell observed:

“In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible. … Political language must consist largely of euphemism, question-begging, and sheer cloudy vagueness.” (Politics and the English Language)

Today, we can see a modern twist: surveys are used to “reveal” popular support for the indefensible (once it’s been sanitized), lending it a veneer of democratic legitimacy. This is what I call “poll-washing.”

For instance, Trump and his allies have described their intentions toward immigrants in openly fascist terms – acknowledging that implementing their plans would be “bloody,” but justified in order to cleanse those who are “poisoning the blood of our country.” Yet we are told that a substantial segment of the Latino population supports Trump’s “mass deportations.” What’s going on?

As I’ll explain in this post, there is abundant evidence, often in the same surveys, that there is much less Latino support for the reality of what mass deportation would entail than for what survey respondents think they are being asked. And, beyond that, the shock value is exaggerated because of how the category “Latino” is constructed by pollsters; more on that below as well.

Surveys vs. Reality

In my last post, “Sleepwalking Our Way to Fascism,” I argued that the most alarming thing now, just two weeks from the election, is how little alarm there is about a second Trump Administration. Eleven months ago, in a deeply researched piece, the New York Times reported on one of the things we should all be alarmed by: that, “If he regains power, Donald Trump wants not only to revive some of the immigration policies criticized as draconian during his presidency, but expand and toughen them,” including “Sweeping Raids, Giant Camps and Mass Deportations.1" In September, Trump himself said at a rally that “getting them out will be a bloody story.”

But that was November, 2023. The headlines last week?

Harris Struggles to Win Over Latinos, While Trump Holds His Grip, Poll Shows (October 13, 2024)

And:

Harris’s Final Challenge: Restore a Splintering Democratic Coalition. Defections from Black and Latino voters are making Kamala Harris more dependent on white, suburban voters — and complicating her path to victory. (October 14, 2024)

Those articles, as well as others (this idea has spread like brushfire), include what seem like startling polling results – that a substantial segment of the Latino population supports some of Trump’s most extreme ideas about immigration, including mass deportations.2

A week ago Saturday, in an interview with Politico Playbook, I explained why this is a misleading conclusion:

“When we do focus groups with the segment of Latinos that are answering survey questions saying that they’re comfortable with mass deportation,” [Podhorzer] said, “what comes out quickly is” that they do not appreciate how draconian and expansive Trump’s proposal could actually be.

“That focus group flips,” he said, as soon as they learn that they or their loved ones could get swept up in it themselves.

Often, Latinos open to voting for Trump presume that his deportation plans are principally aimed at those crossing the border in the last few years. On the contrary, Trump allies have been open that they can and will sweep up non-citizens – documented or not – who have lived here for decades. In particular, when deportation-supporting Latinos are reminded of how a blueprint for Trump’s plans, Arizona SB 1070, was actually implemented in the 2010’s, the politics of “immigration” snap back to what they were at that time – when Mitt Romney’s “maniacal” and “crazy” policy of “self-deportation” alienated Asian and Hispanic voters and helped cost him the election, according to Donald Trump in 2012.

Let’s look at the evidence.

The problem is that surveys ask about the abstract idea of “mass deportation” rather than the known particulars of Trump’s intended mass deportation. Here is a sampling of recent surveys that ask about mass deportation and have been used in stories and analysis to state (or cagily imply) that Trump’s particular plans have broad support – even among Latinos – along with responses to other questions in the very same surveys that show most survey takers couldn’t possibly have Trump’s plans in mind when they answer the “mass deportation” question. That’s because the same respondents also favor a pathway to citizenship for the very settled residents Trump intends to deport. (Thanks to Equis Research, which does the most comprehensive and rigorous polling of Latino voters, for compiling these.)

According to Equis:

While 54% of voters in the Scripps/Ipsos poll said they support deportation, a larger share (68%) said they support a pathway to citizenship for Dreamers;

While 56% of voters in the Pew poll said they support deportation, a larger share (61%) said they prefer a way for undocumented immigrants to stay in the country legally. And 58% of voters – including a significant 37% of Trump supporters – support parole for the spouses of US citizens; and

Among Latinos:

While 45% said they support deportation in the NYT/Siena poll, only 29% opposed a pathway to citizenship for all undocumented immigrants in the country; and

While 39% said they support deportation in the NBC/Telemundo poll, only 8% opposed a pathway to legalization for spouses of US citizens, and only 13% opposed a pathway to citizenship for Dreamers.

Although it would take almost no effort, there has been nearly no effort to dig deeper into why “survey question mass deportation” is so popular, when providing a path to citizenship for the people Trump intends to round up into detention centers and deport is even more popular.

This is extremely dangerous for two reasons:

A potentially decisive number of voters (not just Latinos) who would vote for Harris if they knew Trump's actual plans could stay home or vote for Trump; and

Should Trump win, it will appear that he has a mandate for his mass deportation plans.

Now, let’s take a closer look at what’s missing in the media’s analysis of who “Latino voters” are, just in terms of the kind of data readily available to them. To be clear, I think they have driven into a survey-based epistemological cul-de-sac to the exclusion of many factors that don’t show up in surveys. But for now, we’ll stick with survey data.

Identity Matters; Demographics Don’t.

Identity is one of the most powerful determinants of voting, especially when it triggers a sense of threat or “linked fate” in a group. That’s why knowing how people identify themselves is a powerful predictor of political behavior, and accounts for the very high partisanship of both Black voters and white Evangelical voters.

But just because a person can be described by pollsters and pundits as being part of a group, doesn’t mean that that person identifies as a member of that group. Democrats continue to rack up big margins with voters who strongly identify as “Latinos,” “working class,” or “feminist,” and do less well with those defined as such by demographers and lumped together in survey crosstabs.

(I’ve written a great deal about the flaws of what I call demographic essentialism, which involves these kinds of errors. Survey-driven demographic essentialism is one of the conceptual fiats that improperly define political discourse. These conceptual fiats are the accepted way of thinking about politics simply because they are the accepted way of thinking about politics, but they have never been substantiated. They endure because they are essentially vague to the point of being unfalsifiable.)

A key question in the most recent NYT/Siena survey asks, “How important is being [race/ethnic group] to how you think about yourself?” The following graphs show that Blacks and Latinos for whom their racial identity is “extremely” or “very important” support Harris by a slightly larger margin than they recall supporting Biden by in 2020.

But two things stand out for those for whom being Black or Hispanic is “not very” or “not at all important”: (1) based on their recalled vote, they supported Biden by much less than those for whom it is important, and (2) their support for Harris is substantially lower than even that.

In a September survey in battleground states, Equis Research found similar results, with 72 percent of those supporting Harris saying their “Hispanic or Latino” identity was “extremely” or “very important” to them, compared to just 43 percent of those who supported Trump in 2020 and 2024.3

Equis also found that Hispanic identity is more salient, not less, to Latino voters who have newly registered to vote since 2020. As I’ve explained, younger and newer voters are a critical part of the anti-MAGA vote Harris needs to win – but they are also less likely to take the threat of Trump seriously. And the less they take the threat of Trump seriously, the less likely they are to bother turning out to vote against him.

Identity Politics Tradeoffs

When Trump began his 2016 campaign with “Mexican rapists” and the like, Hillary Clinton was very aggressive in calling out his bigotry. Her slogan was “Stronger Together.”

When Clinton lost, she was immediately criticized for her heavy reliance on “identity politics,” including with regards to immigration. Everyone pointed to how poorly she had done with white voters – but no one noticed how much better she had done with Latino voters than House Democrats running on the ballot with her – 19 points better nationally!

Four years later – when Biden, like House Democrats in 2016, mostly avoided those issues – when immigration rhetoric receded from media and public discourse, Latinos rarely listed immigration as a top concern in pre-election surveys. And Biden did about as well with Latinos as House Democrats had in 2016 and in 2020.

How to read this chart: in 2020, Biden’s margin with White non-college voters was 5 points greater than House Democrats’ average margin nationally.

To corroborate this point, the chart below shows that the higher the Latino density in a congressional district, the better Clinton did relative to Democrats running for the House in the same districts.

Now, imagine if Biden’s election had come before Clinton’s. We would be hearing about why she so dramatically improved on his performance with Latinos. The answer would be pretty obvious – Clinton did much more than Biden to foreground Trump’s anti-immigrant and anti-Latino hate speech. According to Pew, ahead of the 2016 election, immigration was “a top voting issue for Latino voters, second only to the economy.” Pew did not find that to be the case in 2020, when according to the Wesleyan Media Project a much smaller share of Trump’s advertising addressed immigration than in 2016, and Biden’s less than Clinton’s.

It seems unlikely that linked fate was felt as acutely in 2020 as it was in 2016.

Now, with that in mind, let’s look at a typical chart describing Latino defections with this context added.

To do that, this next graphic (inartfully) combines one made by the New York Times (blue and red numbers on the left) with data from Catalist, one of the sources for the New York Times’s estimate. Compare the NYT’s margin for presidential races among Hispanics with Catalist’s (side by side). You can see no disagreement at all for 2016, and while Biden’s 2020 drop is a couple of points more in the Catalist data than in NYT, it’s basically the same story.

But, now let’s look at the congressional margin, which this NYT chart doesn’t show. In the last column, I added Catalist’s estimate for the margin for Democratic congressional candidates from the past two presidential cycles. There’s no change from 2016 to 2020! Moreover, there’s not much difference between those congressional margins and the NYT’s 2024 Presidential estimate.

To be clear, I am not passing judgment on the overall efficacy of either Clinton or Biden’s positioning – just expressing bewilderment that people are surprised that there are predictable tradeoffs in politics. Indeed, nearly everyone offering campaign advice, whether it’s coming from the left, center or right, reflexively attributes Democrats’ gains with this or that group to their advice being taken and losses to their advice being ignored – all the while ignoring all other factors at play and the reality of predictable trade-off losses with other groups.

The bottom line is, the supposed “realignment” on race we currently see in polls is much more about how salient racial identity and threat is in the election than it is about the various other explanations thrown out based on policy preferences, etc.

Divisions in the Latino community that explain more than the ones you’ve read about

In its recent deep dive, the New York Times was typical in looking at gender, age and education to explain Hispanic voters.

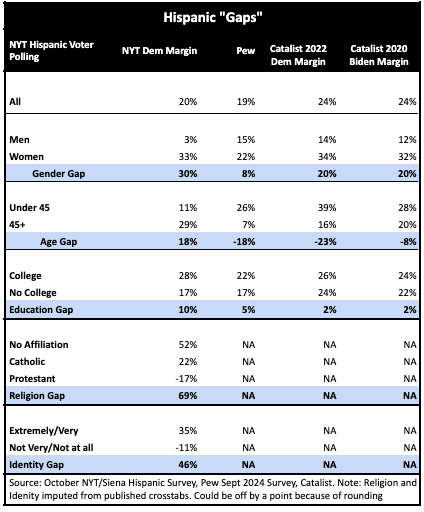

However, evidence of more significant divisions was apparent in the same survey! The following chart does two things. First it compares the NYT/Siena survey’s three published gaps, of which gender is the largest (30 points), with the two that the Times didn’t include in the summary table above, both of which were substantially greater – Hispanic identity (46 points) and Religion (69 points).

Secondly, the Pew and Catalist tables provide different sources of data for the same gaps the Times tracks. This helps us see that, as I’ve explained before, “gaps” in demographic crosstabs often vary widely between surveys. NYT/Siena shows a much larger gender gap than Pew in a contemporaneous survey, and is about 10 points more than Catalist in both 2020 and 2022. More dramatically, NYT/Siena has the age gap going in the opposite direction from both Pew and Catalist. And the NYT/Siena education gap is also substantially greater than the other two sources.

Religion

In “Confirmation Bias Is a Hell of a Drug” and elsewhere, I’ve gone to great lengths to show that religious affiliation, more than any other variable, including educational attainment, is the most salient dividing line for white voters. According to the Pew validated voter study, in 2022, the white Evangelical gap was 80 points (D+6 vs R+74) while the white educational gap was 39 points (D+5 vs R+34).

But it would surprise most people to know that Evangelical affiliation is just as much a divider for Latino voters as it is for white voters. And when pundits scold Democrats for losing Latino voters, they never include this context.

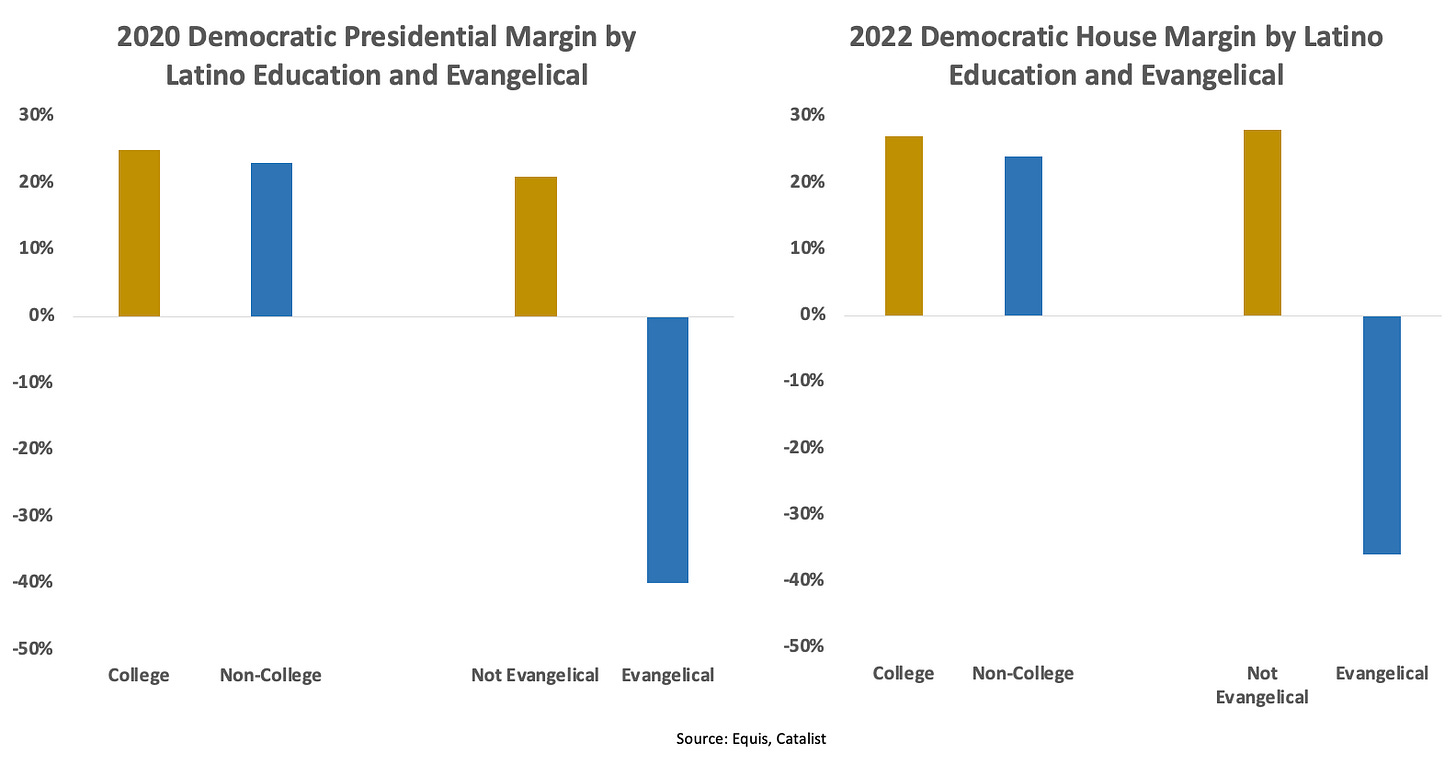

Thanks to Equis, a clear picture emerges. In 2020 and 2022, the Latino Evangelical vote was about 60 points Republican and the Latino educational gap was less than 10 points for Democrats. The following graphs show this for the 2020 presidential election and the 2022 House midterms. Indeed, Latino Evangelicals voted for Republicans by as great a margin as white non-college voters did.

This shouldn’t surprise us. In Prosperity Gospel Latinos and Their American Dream, Tony Tian-Ren Lin writes, “These churches are powerful institutions with significant economic and political influence in the towns and cities they call home.”4 Of the eight House Republicans representing majority-Latino districts, six of them represent districts with above the median Evangelical density.

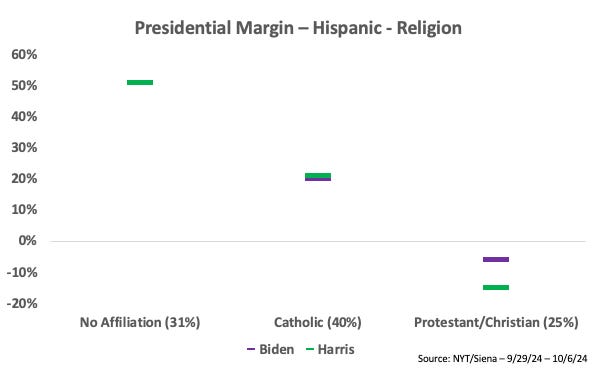

The NYT/Siena survey confirms the stark religious and partisan divide among Latinos. The following graph shows that Hispanics claiming no religious affiliation, and who account for about a third of Latino voters, favor Harris by nearly 3 to 1. The plurality, Catholics, favor Harris by about 3 to 2. But the last quarter of Latinos, “Protestant/Christian” actually favors Trump. Notice that the level of support and recalled support for Biden hasn’t changed for the first two, but has for Protestant/Christian.

Pan-ethnic identification (or lack thereof)

The most basic assumption demographic storytellers make is that it makes sense to apply a pan-ethnic description to everyone now rolled into either “Hispanic” or “Latino.” Yet, according to the Pew Research Center, “Pan-ethnic labels like Hispanic and Latino, though widely used, are not universally embraced by the population being labeled.” Indeed, Pew found that a bit more than two thirds chose something other than a pan-ethnic identity.

This shouldn’t be a surprise. Think back to earlier waves of immigration. A century ago, those already here did little to differentiate immigrants by their countries of origin when they arrived at Ellis Island. But that was certainly not the case for the immigrants themselves, residentially clustering and maintaining their separate German, Italian, and Irish identities, churches, and customs for generations.

Which brings us to one of the most obnoxious habits of the demographic storytellers: going even beyond their conceptual fiat category “Hispanics” and combining that group with Blacks to create the category “non-white.” If (per Pew, above) only 30 percent of the “Hispanic” category accept a pan-ethnic label over their national heritage or over being American, I’m pretty confident that few, if any, Hispanic American think of themselves primarily as “non-white.”

Again it shouldn’t surprise us when partisan trends of those immigrating from Latin or Hispanic countries bear broad resemblance to the similar partisan trends seen in earlier waves of European immigrants, who were first seen as “non-white” as well. Take, for example, this useful chart from Pew.

And, it’s important to understand that according to Pew, “rapid growth is no longer coming from new immigrants naturalizing — it’s being driven by the birth of new generations of Latino and Hispanic Americans who are becoming further removed from the immigrant experience and, in turn, becoming assimilated and acculturated to the American experience.”

We see the same kind of assimilation in the following graph, which shows (1) how much more prevalent marriage to those who are not Hispanic has become since 1980, and (2) that this is now the case for nearly half of the native born Hispanic population. This is just one example of the kind of assimilation that makes a hash of the rigid definitions behind crosstabs that are then used to draw questionable conclusions.

Weekend Reading is edited by Emily Crockett, with research assistance by Andrea Evans and Thomas Mande.

To be clear, much of the Times reporting conveys a much richer and more nuanced picture of what is actually happening - for instance, that many Latinos do not believe that Trump will follow through on his rhetoric, and that others draw a distinction between their own friends and relatives who entered the United States illegally and more recent immigrants. But the headlines and stories narrating the polling numbers are given much more prominence.

Equis State Series Poll (Wave 7/September 2024)/2,500 registered Latinos in 7 states.

Lin, Tony Tian-Ren. Prosperity Gospel Latinos and Their American Dream (Where Religion Lives) (pp. 7-8). The University of North Carolina Press. Kindle Edition.