Terrible Food, and Such Small Portions

How survey-centric political reporting distracts and distorts our understanding of American politics

There’s an old joke about how two elderly women are at a resort, and one of them says, “Boy, the food at this place is really terrible.” The other one says, “Yeah, I know – and such small portions.”

Terrible food and small portions is also an apt description of current political reporting on polls, particularly around demographic trends. The first part of this post explains why, with respect to results for commonly referenced demographic groups, the polling at this place is often “really terrible.” The second part of the post shows that even if you want to think about politics in terms of demographics, the portions are unnecessarily small, because there’s more that could be done with the data.

In the last three posts1 I've used Pew’s “gold standard” validated voter report on the midterms to shed light on problems with the way the media almost always (and academics very often) analyze politics, and the limits of data journalism as it is currently practiced. A key theme in all of these posts has been the media’s misguided obsession with understanding trends in the political preferences of overly broad demographic groups – such as whether non-college or Latino voters are abandoning Democrats.

I want to be clear that my purpose in writing these four posts about Pew and the media is not absolute nihilism – that everything, everywhere is wrong and that there is no point in trying to use data to understand voters and elections. It’s to make clear how to tell the difference between data science and what I call data scientism – asserting (often cherry-picked) data points that lack external validity (often based on demonstrably false but obscure assumptions, and often based on data unavailable for peer review) as conclusive evidence for positions that would otherwise be difficult to justify. (And, in the case of political reporting, these positions tend to fit with broader punditry narratives about electoral trends and American politics at large.) Data scientism is often deployed by writers who promote their own policy preferences by ascribing those preferences to subgroups they say Democrats need to win. Even when narrowly accurate data points are invoked, data scientism relies on some combination of ecological fallacies, conflating correlation with causation, and confirmation bias for its persuasive power.

Terrible Food

As I explained in “All Politics Are Local; All Political Data Is National,” when it comes to specific demographic groups or subgroups, the differences in partisanship we see from poll to poll are almost entirely noise. By “noise,” I mean the completely predictable static that comes from polling’s inherent margins of error, as well as the heavy weighting that is now standard given vanishingly low response rates. This means that almost any time the media writes about demographic trends in partisanship, it’s not offering us important new information; it’s just narrating noise – conflating inevitable statistical and methodological variation with changes in voters’ preferences. The media’s amplification of this noise drowns out any possibility of discussion or analysis that would help Americans understand the actual dynamics of elections or the real stakes.

(Demographic) Horse Race Polling

Let’s start by noticing that the only benchmark against which pollsters judge their work is the final outcome of each election. But what about the outcome for each demographic group? As some responsible analysts occasionally caution, the margin of error for individual demographic groups is much higher than for the entire electorate in any poll. But that doesn’t prevent those same analysts from making bold claims about demographic groups on the basis of data points with very significant margins of error. (Or, even more absurdly, routinely attaching decimal points to their estimates, which serve no other purpose than to make readers unconsciously give the estimate greater credence.)

After an election, we can check the accuracy of the overall trial heat polls against the “ground truth” of the overall election outcome. (The press doesn’t always do a good job of this, however. Notice the logical inconsistency that whenever a frontrunner does 2 or 3 points better in a survey taken two weeks before an election than she did in a survey taken two weeks before that, it is breathlessly reported that she is opening up a lead, or has momentum on her side. If she wins, but by two or three points more or less than the more recent survey, that earlier survey will be celebrated as evidence of how well polling did that cycle.)

Crucially, we can never validate the accuracy of a survey for estimates of individual demographic groups’ preferences, because we have a secret ballot. As a result, there is no final check on whether the polls we heard about all cycle – or even the final post-election surveys – actually got their estimates of demographic groups' voting choices right.

Without this final check, the only way we might have confidence in estimates for subgroups is if several polls weighted to the final results yielded similar estimates for the subgroups. But if those very informed estimates are not at all close? Well, it’s all the more reason to make you question the headlines about pre-election demographic political trends.

The following table puts this to the test by comparing four highly respected sources of post-election data (Pew, Catalist, CNN, and VoteCast), as well as the final pre-election New York Times/Siena survey.2 Those five polls are among the best we have; much, much more was spent to conduct them than surveys we are used to seeing before the election, the sample sizes are quite large, and very smart people do their best to get it right. And remember that with the exception of the Times, they all know the final result.3

This chart compares the Democratic margin in each of the surveys for age, race/ethnicity, and education, by far the most frequent demographic subgroups used by the media. In each horizontal row, the brownest cells indicate the most Democratic margin for that cohort for any of the five surveys, and the yellowest cells indicate the least Democratic margin. For example, Pew had the most Democratic margin of all five polls for voters 18 to 29 years old (37 percent) and Times/Siena the least (12 percent). (The “Democratic margin” is the Republican share of the vote subtracted from the Democratic share.)

As you can see, many of the ranges here are quite large. Now think about how often you’ve read about changes in demographics of much less than in the Range column as conclusive evidence of some Big Trend Democrats Have To Worry About.

Again, the differences in the table above are not over time (i.e., a trend), but at the same time (i.e., all of the differences arise from different methodologies). So, if someone wanted to punk you, they could tell you that the Pew survey was conducted in September and the VoteCast survey was conducted in October, and you would believe that Black support for House Democrats had dropped 19 points. On the other hand, if you were told that the VoteCast survey was conducted in September and the Pew survey was conducted in October, you would be cheered to see House Democrats’ 19 point gain with Black voters. But, of course, they were not taken at different times; they were taken at the same time, and the differences tell us much more about the pollsters than those being polled.4

What’s worse, these large ranges in surveys taken at a single point in time compound when making comparisons across elections. This can lead to very different conclusions based on which polling source you look at. Again, for the two years leading up to the midterms, the most common reporting about polling claimed that Democrats were rapidly losing support from non-college voters and from Latinos. Let’s look at both of those demographic groups in turn, beginning with education.

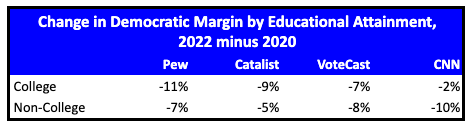

According to both surveys connected to the voter file (Pew and Catalist), the decline in support for Democrats was greater for those with degrees than those without degrees. VoteCast reported no difference.5 Only CNN reported results consistent with what “everyone knows” about how Democrats are losing non-college voters at an alarming rate. (Remember that the overall change in Democratic margin from 2020 to 2022 was about 7 points, so Pew, Catalist, and VoteCast are reporting that non-college voters were in line with the across-the-board decline in support for House Democrats.)

Here is just a sampling of exaggerated reporting about non-college voters: Democrats’ Long Goodbye to the Working Class | The Atlantic; The Democrats’ Working Class Problem Intensifies | AEI; The Democrats' Working Class Voter Problem | The Liberal Patriot; Why Democratic Appeals To The 'Working Class' Are Unlikely to Work | FiveThirtyEight; How the Diploma Divide Is Remaking American Politics | Intelligencer; How Educational Differences Are Widening America’s Political Rift | The New York Times; The ‘Diploma Divide’ Is the New Fault Line in American Politics | The New York Times; Playbook: Inside the ‘diploma divide’ shaping 2024 | Politico; Biden loses ground with working-class Black, Latino voters | Axios. As far as I can tell, there has been no reporting in those outlets, or by those authors, resolving the discrepancy between post-election results for non-college voters and their pre-election reporting, and many are already writing about 2024 as if the 2022 results had actually vindicated their expectations.

Now, let’s look at Latino voters. The following table shows that the two voter-file-based methodologies estimated Democrats’ decline among Latino voters to be on par with their decline among white voters. However, VoteCast and CNN results were consistent with the conventional narrative that Latino support declined much more. This is a perfect example of how inaccurate polling can compound over years into false trends. In 2020, CNN and VoteCast showed much greater margins with Latino voters than the other two. Those greater margins were never verified, but are now frequently used in political reporting to “prove” that Democrats are losing Latino support.

Here is just a sampling of exaggerated reporting about Latino voters: Why Democrats are Losing Hispanic Voters | The Atlantic; Democrats are losing Latino voters as Republicans eye opportunities these midterms | NPR; GOP Gaining Support Among Black and Latino Voters, WSJ Poll Finds | WSJ; A Shrinking Margin; Democrats lost ground with Hispanic voters in 2020. It doesn’t seem to have been a blip. | The New York Times; Why Are Democrats Losing Latino Voters? | Bloomberg Línea; Democrats Lose Support Among Latino Voters Ahead Of Midterms, NBC News Poll Shows | NBC News; Democrats’ problem with Hispanic voters isn’t going away as GOP gains seem to be solidifying | CNN; Dems lose ground to Republicans with Latino voters ahead of 2022 midterm elections | Fox News; Poll: Republicans Beat Democrats among Hispanics, at 27 Percent among Black Voters | National Review. Notice the range of news outlets that have given credibility to this trend. Once again, as far as I can tell, there has been no reporting in those outlets, or by those authors, resolving the discrepancy between post-election results for Latino voters and their pre-election reporting, and, once again, many are already writing about 2024 as if the 2022 results had actually vindicated their expectations.

Demographic Composition of the Electorate

The following table shows each survey’s estimates of the share of the electorate for each of the demographics in the previous table. Here the lowest values are yellow and the highest values are brown. It shouldn’t be surprising that the range of estimates are narrower for portions of the electorate since they change very little from election to election and are tethered to the Census estimates for that demographic as well as estimates of that group’s turnout in previous cycles. (In other words, for example, the latest Census showed that Black Americans make up 12 percent of the citizen voting age population (CVAP), so pollsters know that a result more than a point or two more or less than that would be very unlikely.)

Before we leave composition, it’s important to note that we do know the composition of the electorate by age, because age is on the voter file in nearly every state. That’s why the Pew and Catalist estimates of the composition by age are nearly identical; both are voter file based. Now, look at CNN and VoteCast – they are consistently off what actually happened. This is important because neither of them go back and reweight their results once it is known what the actual composition was. (Remarkably, neither does the Census in their biennial Voting and Registration series, which relies exclusively on the Census' own surveys.) This is problematic, because the demographic partisan preferences reported by those two sources (which, as you will see in the section below, are directly connected with their estimates for groups’ share of the electorate) are routinely used to proclaim new demographic trends by comparing them with the latest polling results.6

Squeezing the Balloon

Those differences in estimates of the composition of the electorate are important because they “squeeze the balloon” in a way that distorts our understanding of vote choice. Here’s an easy example. Let's say all women weigh 90 pounds, and all men weigh 110 pounds. You weigh ten people but don’t know the gender composition and the average weight is 105 pounds. If you begin by assuming that half were men and half were women, your “crosstab” might be that women weigh 97.5 pounds and men weigh 112.5 pounds, and you would be wrong about both.

Now, let’s look at that in the actual surveys. By all accounts, those 65 and older lean Republican and those 18 to 29 lean Democratic. The Pew survey has the highest estimate of the older group’s share of the electorate. And, voila, Pew's estimate of the younger group’s partisan preference is the most Democratic. The extra “weight” on the Republican side (more senior-citizen voters) required the balance of extra “weight” on the Democratic side (higher margins among young voters7). On the other hand, VoteCast, which assigns the smallest share to the older group among our five surveys (meaning fewer Republican votes), also shows the lowest Democratic partisanship for the younger group (once again creating balance).8 Squeezing the balloon.

How does this happen? If you know, based on the final result, that the overall result of the survey has to be R+2 or R+3, and you have strong priors that inform the weights set for each demographic segment, then the voting preferences you report for each demographic will depend not only on the preferences in the raw data, but on the constraints you’ve created with your assumptions about the proportions each subgroup should constitute in the overall electorate.

Margin of Error Redux

Pollsters often report the margin of error on their surveys. Go back to the first chart on Democratic margin by demographic subgroup for the five surveys (the first brown to yellow chart). In the rightmost column, the range of estimates for each demographic subgroup is tallied. For voters 18 to 29, the range in estimates is about 20 points. Divide that by 2, and the revealed margin of error is actually more like +/- 10 points, far more than any pollster ever reports for estimates, and never mentioned by pundits who want to rely on those estimates to back up some big conclusion about the electorate.

Such Small Portions

In this section, I want to call attention to one of the truly inexplicable shortcomings of demographic storytelling in politics. We hear about partisan preferences, and we hear about composition of the electorate – but never the two together. Without those two pieces of information together, however, there is literally no way to evaluate how important it is that Democrats are gaining or losing ground with this or that demographic group.

So, what follows here is not how I think we should think about demographics in understanding elections (I don’t think we should), but, if I actually thought those groups were important, how I would report on them.

As longtime readers know, I offered a new metric, Contribution to Democratic Margin, as a simple and clean way to express the impact of any group (demographic or otherwise) on Democrats’ electoral success or failure. Contribution to Democratic Margin, or CDM, is simply the partisan preference of a group multiplied by that group’s share of the electorate. This calculation can tell us how much that group contributed to Democrats’ margin in the election.

Here’s a simple example. Let’s say that Group A is 10 percent of the electorate and that the other 90 percent are equally split between the Democrat and the Republican. Now, let’s say that Group A favors the Democrat by 90 percent to 10 percent, an 80 point margin. Multiply 10 percent times 80 percent and you get 8 percent, which in this case is both the CDM for Group A and the Democrats’ overall margin of victory. (If the Democrat was ahead by 10 points already with the other 90 percent of the electorate, she would win by 17 points (8 points + 90 percent times 10 percent). If she were behind the Republican by 8 points with the rest of the electorate, she would squeeze out a win by 8 tenths of a point (8 points + 90 percent times -8 percent).)

Contribution to Democratic Margin - The Midterms

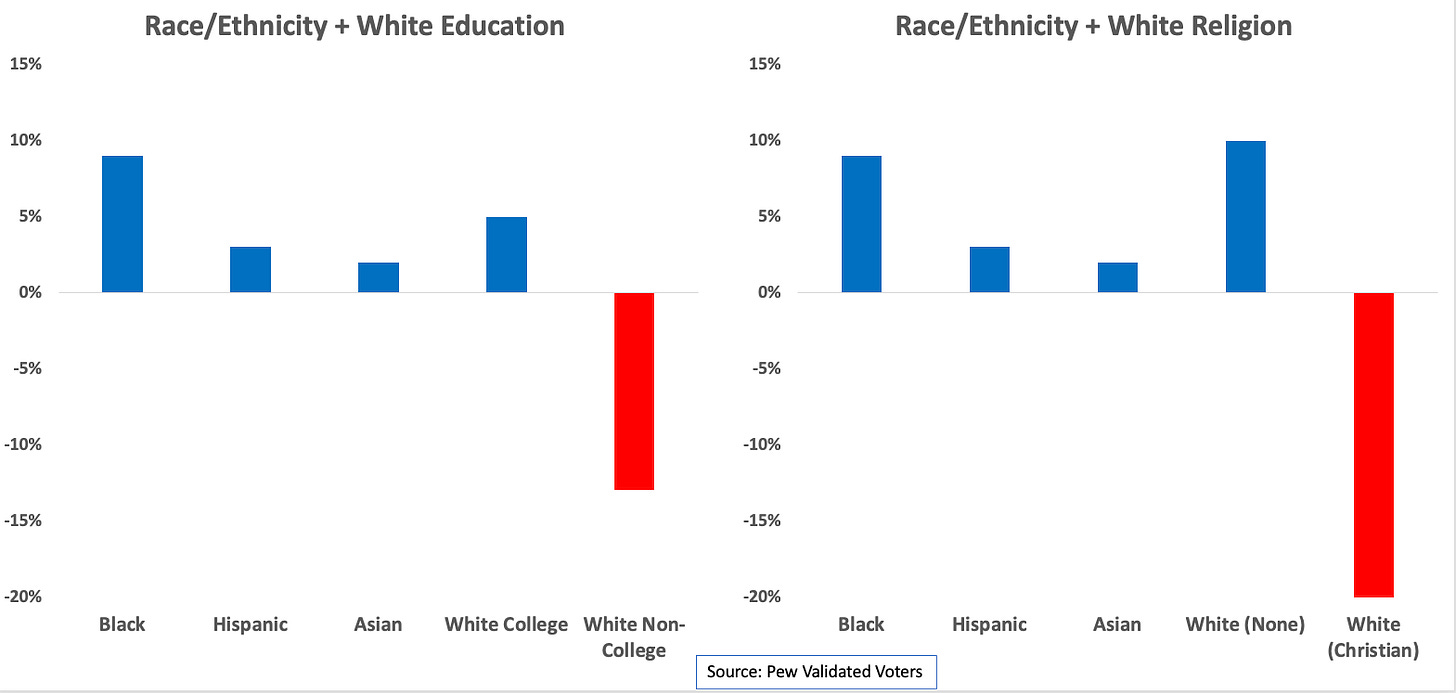

I am going to use the Pew data for this section because it has the greatest variety of subgroups. We will begin by looking at the results through the most common lens – race and white education. The left panel is altogether familiar – how well Democrats did with each group. (The two black bars represent the national vote, with the left bar representing Democrats and the right bar representing Republicans.) The right panel is revelatory, in that it clearly shows the demographic see-saw of American politics – Black voters and white non-college voters nearly balancing each other and the other groups making smaller contributions to Democrats. (Again, the black bar represents Democrats’ margin with all voters, and underscores the see-saw.)

As we saw in “All Politics Are Local; All Political Data Is National,” however, national aggregates hide very different realities in Blue, Purple, and Red states. The next chart shows the see-saw in each of the regions, according to Catalist data for everyone currently on the voter file who has cast a ballot in 2016 or later. The two big take-aways? 1) In Blue states, all of these five groups, including white non-college, are on the Democratic side of the see-saw; and 2) The difference between Purple and Red is that white voters are less Republican leaning in Purple states. (Note: the black bar is not missing in the Purple panel - the value is 0.)

But, as regular readers know, I think it’s much more important to look at white voters through the lens of religious affiliation than by education. Now, with CDM as our guide, we see just what a heavy weight white Evangelicals are on the Republican side of the see-saw. But we also see that white voters who are not affiliated with Christian religions are as significant a weight on the Democratic side of the see-saw as Black voters. (To be clear, I am not making a statement about the relative importance of Black voters and white non-Christian voters, as the latter is a category I’ve created only to illustrate the limitations of looking at education rather than religion.)

In the next chart, I’m going to combine all white Christians to make a CDM chart comparable to the conventional race/ethnicity + white education breakdown. The right panel (using religion) is much more clarifying when it comes to white voters than the left panel (using education). The ridiculous irony of ignoring white Christian religion is that of all the electoral segments in the Pew report, white Christian religion is the only one for which there’s: 1) a clearly understood set of values and political worldview associated with it, 2) a billion dollar communication industry that continuously promotes its political preferences, and 3) a weekly reinforcement of that worldview for most of its adherents. Not to mention, megachurches play an essential role in setting the political tone beyond the devout. To that point, the Pew study reports that in each of the last four cycles, nearly half of Republican voters attended church services at least once a month, and regular church-goers favored Republicans substantially, with a big jump coming in 2022.

Now, of course, you can analyze CDM with any group you want, with interesting results. Among the 130+ categories in the Pew study, the best CDM groups for Democrats are religiously unaffiliated voters (+13),9 Black voters (+8), and unmarried voters (+8). The worst CDM groups for Democrats are white Christian voters (-21), white non-college voters (-14), and white voters over 50 (-13).

The following graph reproduces the data in the earlier table of Democratic margins by race/ethnicity and white education. You can see the variation.

But now, let’s look at how the five surveys compare when we look at CDM by race/ethnicity and white education. There is much less difference across surveys. Again, we can see the effect of squeezing the balloon – the greater the Democratic margin, the smaller the share of the electorate.

Contribution to Democratic Margin Over Time

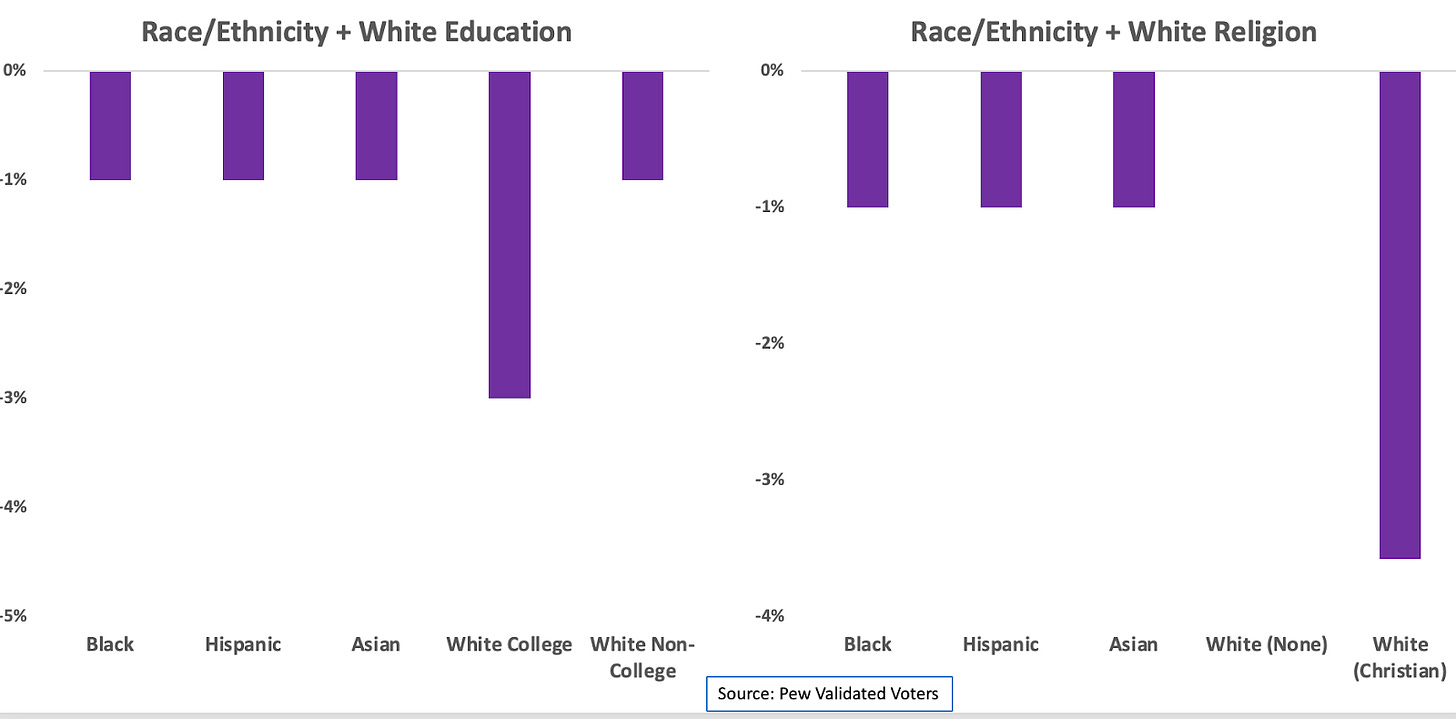

Now, we can use CDM to get a different take on Democrats’ 6 point drop from 2020 to 2022. The results, based on Pew, are not what you would expect. Parsing the white vote by education shows that Democrats were hurt more by changes in the white college vote than the Latino vote – wait, what? How many times have you read that Democrats were doomed by declining support from Latino voters? And if you read anything about Democrats and white college voters, it was about how the party is supposedly captured by out-of-touch members of this demographic. Parsing the white vote by religion shows that the largest hit to Democrats came from white Christians – again, something you read nowhere.

Finally, consider the context that CDM provides for claims to the significance of demographic subgroups’ partisan preferences. In the end, Democrats’ poorer performance with Latino voters relative to 2020 cost the party only 1 point nationally. That’s important – it’s about the same cost as poorer performance among Black and Asian voters (again, the drops for each of these groups mirrored national trends that are characteristic of a midterm for the president’s party). And, in pundits' taxonomy, the chart above confirms that Democrats’ drop with white college (not white non-college) voters was the most consequential – and if religion is considered, the drop with Latino voters was less than a fourth as consequential as the drop with white Christian voters.

Furthermore, when we see declines in support from Democratic-leaning groups that are an increasing share of the electorate, ignoring CDM means risking ignoring that this still may be good for Democrats, when that group’s increasing share of the electorate displaces a Republican-leaning group’s share. For example, assume the electorate is 100 voters. Let’s illustrate with a group of 10 voters who favor Democrats 90 percent to 10 percent (9 vote for the Democrat, 1 votes for the Republican). Now, let’s say in the next election, that group’s support for Democrats drops to 80 percent to 20 percent – OMG! Democrats are doomed. But let’s say the electorate is still 100 voters but our group has grown – there are now 15 voters. That means there are now 12 Democratic votes and 3 Republican votes. The group now nets Democrats 9 votes, compared to 8 votes when Democrats’ claimed a greater share of the group’s voters, but the group was a smaller share of the electorate.

Conversely, you see that Democrats can do worse with a Republican-leaning group without losing ground in the final results, if that Republican-leaning group is a diminishing share of the electorate. Obviously, white non-college voters fit this bill.

Conclusion

If you’ve found this and the other posts in this series convincing, you might ask yourself: If most polling trend pieces are meaningless, then how should politics be reported?

Categorically, the most important change would be for polling to be seen as one of a number of other important sources of evidence that could be used to triangulate a better understanding of elections, rather than THE definitive last word on the matter. Here are some other modest suggestions that would go a long way to improving the use of polling in political coverage and commentary.

Whenever possible, use polls that avoid ecological fallacies. For example, if you want to use polling to get a better handle on the presidential race, limit your coverage to polls of people in the states that will decide the election.

Instead of talking about national trends, cover Red, Purple, and Blue states independently.

Whenever reporting polling results, put them in context. That means (1) compare the results to other polls, (2) contextualize the meaning of changes using CDM or something like it, and (3) contextualize it so the results can be understood along with the fact that so few individual voters are changing their partisan minds. It is especially egregious that pillars of the mainstream media regularly report about their own polls as if there aren’t other polls out there too. Literally none of those institutions would report anything important on the basis of just one source, yet that is their routine practice with respect to their own polls.

Do fewer surveys with greater sample sizes if there is going to be reporting on subgroups.

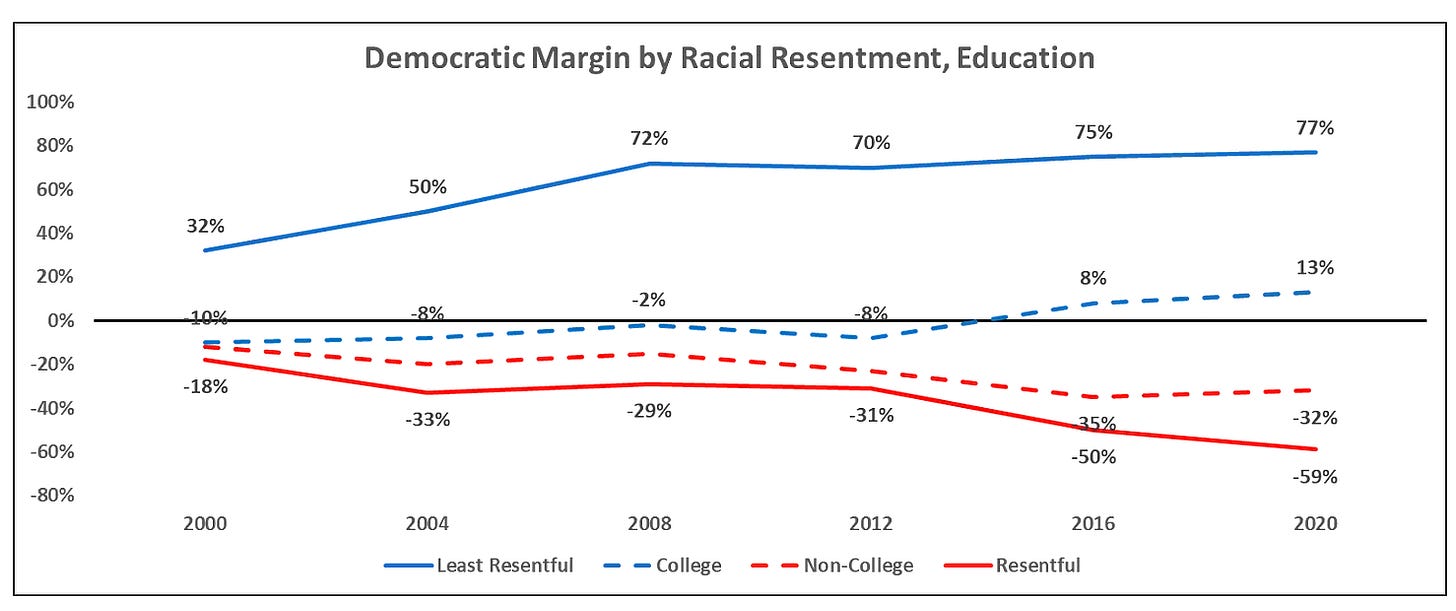

As importantly, there should be clear criteria established for why a subgroup is important. That we spend so much time focused on educational attainment is one of the most important shortcomings in political discourse today. “College” and “non-college” now function as euphemisms to avoid speaking plainly about what divides Americans. Barack Obama’s election, followed by Trump’s election, made racial resentment a much more salient dividing line in American politics, as the solid Blue and Red lines in the next graph make clear.

What divides Americans today is both much simpler and much messier than most pundits (and most Americans) would prefer to acknowledge. It’s the question of what kind of society we want to live in, and who we want to share that society with.

Footnotes:

Confirmation Bias Is a Hell of a Drug showed how the coverage of the Pew report demonstrated the prevailing confirmation bias of the media; only the findings that confirmed conventional wisdom were covered, while those telling a different story were ignored.

All Politics Is Local; All Political Data Is National showed that the national data we rely on to understand politics can’t help us where it matters most – at the state and local level.

Turns Out, Turnout Matters showed that Democrats’ fortunes in the states that decide the Electoral College and control of the Senate depend on sufficient anti-MAGA turnout – which means that to understand politics in the Trump era, we can’t rely on partisan preference.

I included that New York Times survey, because the NYT/Siena survey is recognized by many, including FiveThirtyEight.com, as one of the two most accurate pollsters in 2023, and garnered instant credibility when it was released. Moreover, it was released within weeks after polling began in many places, so it’s unlikely that any deviations were the results of wide swings in voter preferences.

There are two other “gold standard” post election surveys - the ANES and CCES. I don’t include them in this analysis for two reasons: (1) their primary constituency is the academic community, and are rarely brought into the general conversation;; and (2) The midterm data available from these sources differs from their longitudinal election data, and for a number of technical reasons, they are very likely to have subgroup results further from the four surveys here, and I didn’t want to get into a debate about whether I was taking advantage of that to show very wide variations.

Although they differ by a point or so in what they benchmarked, with Pew and Catalist at the lower end and VoteCast at the higher end. But obviously that can’t explain the variation between the surveys. The New York Times/Siena was about two points off nationally.

If you think nobody would make comparisons across different surveys like this, you have too much faith in our political pundits. An excerpt from Josh Kraushaar’s “The Great Realignment” mirrors exactly what I described here; he wrote: “Democrats are statistically tied with Republicans among Hispanics on the generic congressional ballot, according to a New York Times-Siena College poll out this week. Dems held a 47-point edge with Hispanics during the 2018 midterms.” But this “47-point edge” was calculated by using a NYT statistic first, and then a Pew statistic, without noting the switch.

There’s an additional problem with these comparisons - it’s the convention to compare midterm House results with the presidential results two years earlier. While it may seem inconsequential because the difference between Clinton and Biden’s vote share and House Democrats’ vote share in their election years is only a couple of points, as I show in this Substack post, that small overall difference masks much larger subgroup variation. But because 2020 House Democratic estimates are available only from Catalist, there’s no way to incorporate that into this analysis. If I did, the points I’m making would be even more dramatic, especially with respect to Latino voters.

Indeed, it wasn’t until recently that Edison, the firm that does the network exit polls, acknowledged that their results had historically reported too great a share of college educated voters, and had not revised earlier estimates. That, of course, threw off their estimates for the partisanship across the board.

Note - the balloon could have been inflated in any of the other age groups.

Catalist has a high value for the older group as well, but the bulge shows up in the 30 to 44 year old group.

This includes voters of color who are religiously unaffiliated as well.

Very illuminating. It certainly feels much better when volunteering for campaigns to know you're putting your resources into the people and places that will probably pay the biggest dividends in voter turnout for your candidates. When the polling is bad, then often too is the allocation of resources.