Red Wave, Blue Undertow

This analysis provides compelling evidence for a very different explanation of the midterm results than what most analysts are offering – an explanation which I have been arguing was possible for more than a year. Even before November 2021 (when Democrats suffered major losses in Virginia and elsewhere), I argued that America is an anti-MAGA majority country when it knows that MAGA is on the ballot.1 That produced record-breaking turnout in both 2018 and 2020.

I have consistently underscored that to the extent that Americans understood the stakes of the midterms to be about defeating MAGA, they would once again show up in sufficient numbers to bar the door. All that was needed to confound the usual midterm rout for the president’s party was making sure that 2020 voters understood that, just as they didn’t want Trump for President, they certainly didn’t want his criminal accomplices and MAGA fascists to take over Congress and their state capitals.

This midterm bore that out to a stunning degree. Where voters understood the stakes, they voted as they had in 2018 and 2020; where they did not, they met the pundits’ expectations about a Red Wave.

On November 8th, that expected Red Wave washed away Democrats across the 35 states where there were no competitive, top of the ticket MAGA candidates on the ballot. But in the other 15 states there was a Blue Undertow, in which Democrats actually did as well as or better than they had in the 2018 Blue Wave election. In states where MAGA was competitive, Democrats now have four more seats in the House and four in the Senate than they did in 2018 with their Blue Wave gains. Yet, they have 25 fewer seats in the other states. In the MAGA Statewide Competitive states, turnout was exactly the same as it was when turnout records were broken in 2018. In the other states, turnout dropped 5 points.

This analysis is divided into three sections:

Red Wave, Blue Undertow - A look at the results at each level of the ballot to see that, in fact, there were two very different midterms.

How Turnout is Like Super Bowl Ratings - Although there is no doubt that marquee up-ballot candidates won with unusually strong backing from independents and Republicans, a higher anti-MAGA turnout put those competitive races in a range where swing voters could make that difference, and also defeated down-ballot MAGA Republicans.

Procrustean Punditry - How (and why) the people who set the dominant midterm narratives got it so wrong.

The Anti-MAGA Majority

Up until June 2022, everyone expected Democrats to take the inevitable midterm drubbing – the one nearly all presidents’ parties, and all whose president has been underwater, have experienced since Reconstruction. All of the usual midterm indicators – presidential approval, the generic ballot, the November 2021 results, Democrats trailing Biden by five to six points in special elections, Democratic retirements, and more – supported this expectation.

Those indicators reversed in Democrats’ favor with the January 6th hearings and then the Dobbs ruling. Such a reversal has never happened in a midterm since comparable statistics have been kept. While the 1998 and 2002 midterms were not disasters for the president’s party, Clinton and W Bush’s approval ratings were high, and those midterm indicators were not pointing to disaster ahead of the election.

But in mid-October the indicators reversed direction for the second time, which, of course, has never happened either. Suddenly, the consensus was that Democrats were in fact heading for a pretty routine midterm drubbing, perhaps mitigated in the House by new lines that drastically reduced the number of competitive seats. We were told once again that Democrats were losing the all important swing voter, whose choices reliably produce thermostatic midterms.2 Turnout, we were told, never matters.

(Note, throughout, I very deliberately use the term “turnout” as a neutral descriptor of what happened (how many people turned out to vote) as distinguished from “mobilization” (efforts to convince certain people to turn out). Turnout equals voters divided by the citizen voting eligible population (CVEP).)3

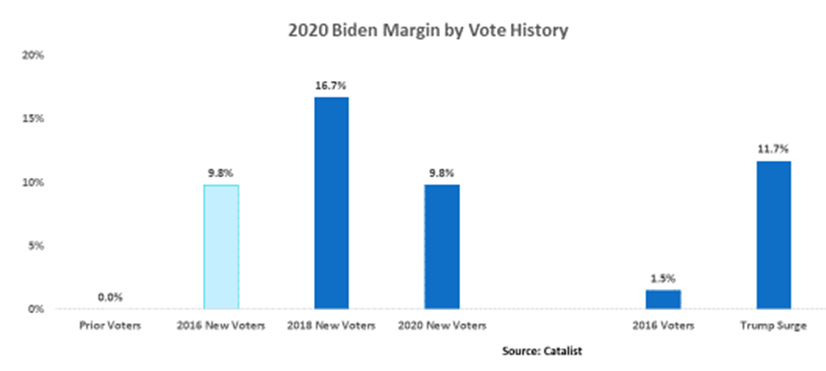

But, as I have been arguing for several years, we have entered a new political era. In this new era, elections will more often than not be determined as much by differential partisan turnout from what I call “New Midterm” voters – Americans who had not been regular voters through 2016, and who decide to vote because they understand that their vote can help determine whether we will be governed by MAGA.4 In 2020, Biden did no better with returning 2016 voters than Clinton had (about +2), but won by 4.5 points because forty million Americans who had not voted in 2016 favored him by 12 points. That is America’s anti-MAGA majority.

The anti-MAGA majority has transformed the landscape of American politics in just the last six years. In 2016, despite losing the popular vote, Trump became president by virtue of his Electoral College victory. That election made clear that Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin had become the fulcrum of American politics.

In those five states, on the day that Trump was sworn in, only one state had a Democratic governor (Pennsylvania), only four Democrats served in the Senate, and Democrats did not constitute a majority in any of the 10 state legislative chambers. Now, four of the five governors are Democrats, nine of the ten Senators will be Democrats, and three of the state legislative chambers will have Democratic majorities.

See Appendices I and II for more detail and data about the new anti-MAGA era.

Red Wave, Blue Undertow

I have long argued that because of the anti-MAGA majority, Democrats could weather the 2022 midterms to the extent that voters understood that the stakes were the same as they were in 2018 and 2020. As it turns out, in states that the Cook Report with Amy Walter, Crystal Ball, FiveThirtyEight and other handicappers classified as very competitive at the state level (Senate and/or governor),5 and in which at least one statewide candidate was identifiably MAGA (whether or not they were endorsed by Trump), 2022 was nearly a rerun of 2018 and 2020. In states where the political and media environment made the stakes less clear to voters, however, we saw the usual and expected midterm results.

This section begins by detailing the role of so called swing voters and then goes through the midterm results for each level of the ballot to show how dramatically different the results were in each region.

The Role of "Swing Voters"

This analysis does not conclude that turnout was all that mattered. The problem with most current midterm analyses is the extent to which they suggest turnout didn’t matter at all. In particular, many pundits are using a single statewide race as a universal exemplar for what happened in the midterms more broadly. Raphael Warnock’s performance in Georgia, for instance, is often used to support the idea that Democrats overperformed primarily because of “swing voters,” and specifically partisan defectors – people who tend to vote Republican and might otherwise have chosen Herschel Walker, but who declined to do so because he was such a terrible candidate.

There is no question that there was net partisan defection towards Democrats who won statewide. Hobbs, Kelly, Warnock, Cortez-Masto, Evers, Whitmer, Shapiro, and Fetterman all ran ahead of Democrats in House races in their states, and the polling I’ve seen showed them with a greater share of Trump voters than their opponents had of Biden voters. Open and shut. As I will show below, however, the “defection” explanation doesn’t hold for other races down ballot. Those who (correctly) emphasize the role of swing voters in these up-ballot races fail to account for why a Republican “swing voter” who found Mastriano unacceptable would also vote for Democrats in more obscure down-ballot races.

Furthermore, the case made for large numbers of Republican defections is made based on inferences drawn from voter registration – which can be notoriously misleading, as in most states there are actually a large number of people who vote like hard partisans but who are nonetheless not registered with either party. Usually when pundits tell you, for example, that “Republicans turned out at a higher rate than Democrats,” they don’t mention that a third or more of voters in each state don’t register as either a Democrat or a Republican. Registration rolls can tell us nothing about the partisan leanings of those who do not register as one or the other party.

According to AP VoteCast,6 Democratic House candidates netted only 84 percent of the vote from 2020 Biden voters who cast a ballot in 2022, while Republican House candidates netted 91 percent of all 2020 Trump voters who cast a ballot. When we make the same calculation based on party ID (how voters identify or lean) instead of 2020 vote choice, the net gain is much closer – 92 percent for Democrats and 90 percent for Republicans. In other words, the net impact of defections was either negligible (based on party ID), or actually benefited Republicans (based on 2020 presidential vote). At a minimum, this confounds the idea that we can generalize from what is true about certain top of the ticket races like Warnock’s to conclude that House Democrats benefited substantially from Republican defections.

Governors

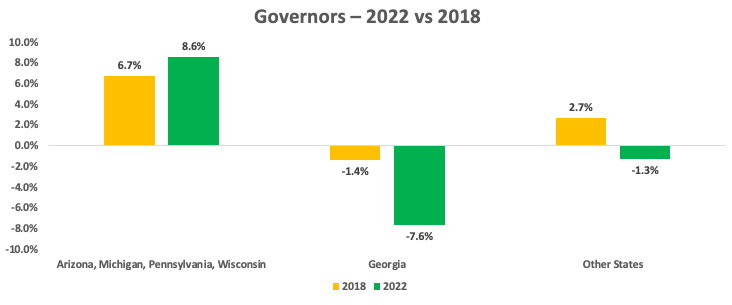

Democratic gubernatorial candidates did better than they had in 2018 in the MAGA Competitive states, but worse than they had elsewhere in 2018.7

Thirty-five states have their gubernatorial races in the midterms. First, consider that in the MAGA Competitive States, Whitmer and Evers won by more than they did in the 2018 Blue Wave, Shapiro won by more than Wolf did, and Hobbs flipped a state Democrats lost in the Blue Wave. Nothing like this has happened in the 21st Century as far as I can tell. Now let’s look at it in terms of how well Biden did two years ago: in the MAGA Statewide Competitive states, Democrats did just as well as Biden did, while elsewhere Democratic gubernatorial candidates ran 10 points behind him.

The gubernatorial races also provide another illustration of the importance of context and the danger of quick generalizations. Let’s divide the gubernatorial states into three categories - Georgia, where Kemp won after rebuffing Trump; the four other contested Electoral College states; and the rest of the states with gubernatorial races. The differences are dramatic. In the four Electoral College contested states, all four Democrats did better than they did in the Blue Wave 2018 midterm by 1.3 points, while those in the other 31 states ran 4 points behind their 2018 margins.

The US Senate

Now, when we turn to the Senate races, we see the same thing – context matters. In MAGA Statewide Competitive states, Democratic Senate candidates ran 1.4 points ahead of Biden; elsewhere, Democratic Senate candidates ran 5.2 points behind Biden!

The House of Representatives

Because the House received nearly all the pre-election attention, and because there are more cases, we can dig even deeper into what happened. Let’s start by comparing this midterm to the 2018 midterm in the 150 closest races8 in terms of presidential swing.9 The left side of the chart below is how we’ve been told to think about the outcome – not great, but not as bad as 2018 and other terrible midterms have been for presidents’ parties. But the right half shows that in the other states, the midterms were nearly identical to those in 2018, while in the MAGA Statewide Competitive states, Democrats did better than Biden had, something almost no president’s party has done since World War II.10

To the extent that we’re offered explanations for why Republicans “underperformed” traditional midterm models, we’re told it’s because Republican candidates were hurt by Trump’s endorsement, or that they were poor quality candidates, or their extremism generally. Shockingly, these other factors never enter into anyone’s analysis:

Candidate status - Whether the Republican was an incumbent, a challenger, or running in an open seat.

Statewide competitiveness - What I’ve been discussing – whether a competitive MAGA candidate was at the top of the statewide ticket.

Racial composition of the district

Size of media market - It stands to reason that the more congressional districts are in one media market, the less likely voters served by that market will be to know much about the congressional candidates on the ballot, especially if they are not incumbents.

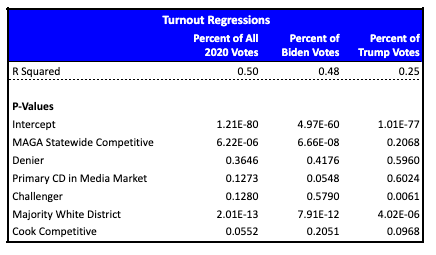

Two factors that have been lifted up in many analyses have been whether the Republican candidate was an election denier,11 and whether the district was competitive, usually taken to be rated as such by the Cook Report. Throwing all those factors into a quick regression, here’s the result:

As you can see, every factor has a P-value less than 5 percent except the one indicating whether the candidate is a denier! In other words, being a denier is the only factor on this list that is not statistically significant with 95 percent confidence. That would make no sense if the primary dynamic was swing voter judgements, but it makes sense if the primary driver is higher turnout of Biden voters – who would vote against the Republican no matter what position that Republican had taken on the legitimacy of the 2020 election.

Another way of seeing how the conventional models miss the boat is to look at how well FiveThirtyEight’s final Deluxe model performed in the 150 races.12 It’s a bit off overall, as is the case for most “final” forecasts. But in the states that are not MAGA Statewide Competitive, the Deluxe model is only 4 tenths of one percent off. In other words, the pre-2016 factors did a great job forecasting the outcome in those 35 states. But in the MAGA Statewide Competitive states, the Deluxe model missed the barn – Democrats’ margin was 0.7 percent, but the model expected Democrats to lose those districts by 4.2 points.

State Legislatures

Finally, let’s look at the level of the ballot where it makes the least sense to argue that the outcome is a result of prudent independents and Republican voters defecting – state legislative races.

Again, it’s obvious that any statewide Democrat who ran ahead of Democratic House candidates benefited from Republican defections and Independents’ preferences. But it’s absurd to say that, say, turnout didn’t matter because Shapiro did so well (because even independents and Republicans couldn’t bring themselves to vote for Mastriano) when the same idea cannot explain why “Democrats won a majority of seats in the Pa. House for the first time in 12 years.” Anti-MAGA turnout flipped the Pennsylvania House; swing voters further ran up the score against Mastriano. (The turnout rate was 3.3 points higher in Pennsylvania in 2022 than it was in 2018.) If a Republican or Independent voter thought that Mastriano and Oz were unacceptable, we have no reason to believe that would cause them to suddenly become straight party line Democratic voters. Very few voters know who their state legislator is, let alone whether or not the Republican candidate is a denier or not. (That’s especially true in a redistricting year, when even incumbents find themselves campaigning to new constituents.)

Nonetheless, unlike other underwater presidents’ parties, in 2022 Democrats picked up state legislative chambers.

How Turnout Is Like Super Bowl Ratings

Every year, the networks can count on all the fans who watched the regular season games to show up to watch the Super Bowl. In addition, plenty of people who aren’t big football fans also watch the Super Bowl – but they can’t be relied on to watch it every year or to even pay attention if they haven’t been invited to a Super Bowl party or there isn’t much buzz about the particular teams, personalities, or rivalries.

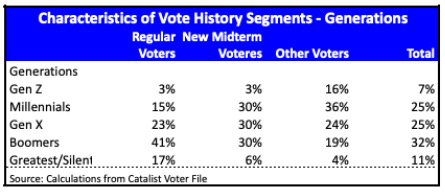

Election turnout is very similar. There is a set of people, Regular Voters, who will reliably show up to vote every Tuesday after the first Monday in November of even years, no matter what is on the ballot. But who else also shows up depends on many other factors. Some people are mildly interested in voting but won’t do it if it’s too inconvenient. Others will only “tune in,” so to speak, if what’s on the ballot seems especially important or there is enough buzz around what's on the ballot – like, for instance, a high-profile Senate race where one candidate is laughably unqualified and scandal-plagued, or a ballot initiative on abortion rights.

Until 2018, Regular Voters dominated midterms, usually constituting about 75 percent of those voting. Within this group, definitionally, the only way to make progress is to change their vote choice. Ticket splitters are much more likely to be found in this group. The second group of non-habitual voters (the casual Super Bowl watchers in our analogy) is very sensitive to the intensity of politics in their information ecosystems. To be clear, this group is not majority Democratic in every jurisdiction, and it is not necessarily ideological. But they are much more likely to be party line voters.

Comparing Regular and Irregular Voters

Let’s begin by looking at the partisanship of Regular Voters.13 Catalist models the current partisanship of each voter on the file with a Vote Choice Index (VCI).14 This is different from party registration – which, again, is notoriously unreliable given the number of people who do not register as Democrats or Republicans. (When pundits talk about how Republican turnout was higher, they use the flawed party registration model.)

According to the Catalist voter file, there are about 87.1 million Regular Voters. Their VCI is minus 2.4 points for Democrats. (That is, they can be expected to break 51.2 to 48.8 for Republicans.) Now, it’s likely that this group of voters was a bit more Republican this year than their average over time because, as we saw, slightly more Biden voters likely voted for House Republicans than Trump voters likely voted for House Democrats. But regardless, Democrats only had a 1.9-point deficit in the House this year – at least a half-point better than we would expect from Regular Voters.

The only way this would make sense is if infrequent voters were more Democratic than Regular Voters. In our new anti-MAGA political era, this is indeed the case. According to the Catalist voter file, there are 39.6 million New Midterm Voters – those who voted in 2018 and 2020, but had not voted in 2014, or, if they were eligible for the first time, voted in 2020. This group’s VCI favors Democrats by 12.7 points. (That is, they can be expected to break 56.3 to 44.7 for Democrats.)

The horizontal bar is at 50 percent Democratic vote share. You can see that in every one of the presidential battleground states, Regular Voters favored Republicans, while New Midterm Voters favored Democrats. Thus, we can see Democrats winning in these states is a matter of whether enough New Midterm Voters cast ballots as well. When enough do, they provide Democrats a majority in each of the states – which is what happened in 2020 and 2022. It’s also worth noticing in passing that we’ve seen Democrats struggle more in Arizona, Georgia, and Nevada than the other three states, where models have nearly half of Regular Voters as Democrats.

With that in mind, let’s use Michigan as an illustration. In Michigan, Catalist modeling estimates that there are about 2.2 million regular voters and they break about 48 Democrat - 52 Republican. In 2022, about 4.5 million Michiganders cast ballots. Now, if the turnout-doesn’t-matter crowd were correct, the additional 2.3 million voters would have an underlying partisanship similar to the 2.2 million regular voters, and therefore, ipso facto, Whitmer and Benson were re-elected because Tudor and Karamo were too extreme – once again, Democrats squeaked through because of swing voters’ good judgment. But if that were the case, then Democrats should have still done poorly down ballot, as those tilting-Republican voters would have split their tickets, reverting to their usual midterm inclinations.

But, instead, Democrats flipped both houses of the state legislature! Consider whether a more plausible explanation for the outcome might be that those additional 2.3 million voters were from the pool of 3.2 million irregular voters who had voted in 2020 and were modeled to be 54-46 Democratic. That would make the modeled outcome for Michigian be 51-49, and the actual outcome in the House of Representatives was … 51-49. So, yes, there were “swing voters” – they gave Whitmer a 55-45 victory instead of a 51-49 victory. But she would have fallen short without those 2.3 million +8 Democratic voters.

In 2018 and 2022, Regular Voters constituted about half the voters in most states, much less than the roughly two-thirds to three-quarters they had in the previous midterms. Thus, it’s not difficult to see that the actual results are consistent with New Midterm Voters constituting the other half of the voters. Regular Voters do not look like America - they are older, and more likely to be white, college educated, and conservative. For a very detailed breakdown on those differences, see Appendix V.

This is the key difference between Trump Era midterms and the midterms before them: in the former, more-conservative Regular Voters were about two-thirds of voters; now they are barely half.

A Final, Confounding Word About Turnout

While the voters who turn out most reliably are more Republican than the rest of the electorate, increased turnout does not inevitably mean better results for Democrats. Here’s why.

If you are a campaign practitioner (as opposed to an opinionator), you don’t think about increasing turnout, you think about increasing your voters’ turnout. (And, let’s be real – you also think about discouraging opposition turnout.)

Republicans do this as well. Remember Karl Rove in 2004 in Ohio? Democrats increased turnout substantially in urban areas, but Rove more than matched that in the rest of Ohio. And Republicans are notorious for their efforts to suppress Democratic voters - by passing laws that make it more difficult for them to vote and, for example, targeting disinformation about Democratic candidates to Black and Latino audiences.

Thus, it is still wrong, as some on the left would do, to assume that increased turnout automatically means better outcomes for Democrats or progressives. However, we know that the majority of voters are opposed to MAGA’s agenda, and that this majority is motivated to turn out in elections where MAGA is salient. So, in the current anti-MAGA environment, increased turnout will usually translate into worse outcomes for MAGA Republicans.

Procrustean Pundits: Defenders of Democratic Myths

In the Greek myth of Procrustes, a robber forced his victims to “fit” an iron bed by either cutting off limbs that were too long or stretching those that were too short. Similarly, most of the people whose job it is to tell us what is true about elections have struggled to make what just happened in the midterms fit into the Procrustean bed of the usual formulas they always rely on.

To some extent, of course, everyone acknowledges that this was not a normal midterm. Nearly all explanations for the outcome make the argument that something Trump related (Trump himself, attacks on democracy, election denial, abortion, candidate quality) was so off putting that a decisive group of voters (such as swing voters, independent voters, or “meh” voters who only “somewhat disapprove” of Biden) broke their historic patterns to reject the out-party. Some embellish that general argument to give Democrats and their allies credit for exploiting those weaknesses. Nearly all of the “evidence” for these explanations relies on the Exit Polls to “prove” that it was this narrow sliver of voters who made the difference, and that concerns for certain specific issues drove their unlikely votes.

Wrong or Insufficient Explanations for the Midterm Results

Here are some of the major things Procrustean pundits have either been exaggerating the importance of while ignoring larger factors, or just getting wrong.

Independent Voters/Swing Voters/”Meh” Voters

By far, the idea that “swing voters” changed their mind is the most common explanation for electoral shifts. Many pundits have turned to this explanation this year because the president’s party won Independents, something that has never happened before.

Although I stand by what I’ve always argued about the unreliability of the exit polls (see below for more on this year’s Exits), if you look at someone’s congressional vote by 2020 presidential vote, by party identification, by 2018 congressional vote, and by Biden approval, you would see that if you consider a prior vote for either Biden or Trump as a voter’s “base” position, it’s pretty clear that to the extent that voters “switched” it was generally towards Republican House candidates, although it wasn’t a big effect.

So why do factoids like the preferences of Independents or those who somewhat disapprove of Biden’s job seem to be incontrovertibly telling us the opposite? Easy. First, remember that many of those who identify as Independents or who say they somewhat disapprove of Biden voted for him in 2020.

Should we really consider it a singular persuasion achievement if those who voted for Democrats in 2020 continued to do so in 2022 just because on an earlier survey question they identified themselves as “independent?” But even more to the point, if those somewhat-disapprovers of Biden might have stayed home in earlier midterms (or in this one if they were in the non-MAGA-competitive states), then it makes sense that “meh” voters favored Democratic candidates since a greater proportion of meh voters were Democrats who usually stay home. It’s not that a greater percentage of a stable group of somewhat disapprovers decided to hold their nose and for the Democrats, it’s that Democrats who somewhat disapprove decided to vote anyway.

Exit Polls

Sadly, exit polls remain the go-to authority of Procrustean punditry. No matter how many times the Exits prove to be wrong, pundits continue to base their early midterm takes on exit polls – because, they argue, Exits are the best early data we have and better than nothing. While they offer caveats about how this data isn’t perfect, they still use Exits to build a narrative that can be hard to shake once better data comes in. And in this midterm, we already have evidence that the Exits were even more useless than normal. In short, the Exits were weighted to an outcome that assumed Republicans won by about three times the margin they actually won by. (See Appendix IV for more detail on how and why the Exits were so off.)

The Trump Penalty

Ahead of the election, Nathaniel Rakich at FiveThirtyEight, among others, compiled an inventory of where Republican candidates were on the results of the 2020 election, from full denier to fully accepting. After the election, a number of analysts (here and here, along with others) calculated that “denier” candidates suffered a “Trump penalty” of about 5 points in Cook competitive races.

That those who Trump endorsed paid a price seems almost too obvious to doubt. But, it turns out that the penalty, if it exists, is much, much smaller than is being reported. Indeed, this is so counterintuitive that I’ve gone to great lengths to make sure I have it right. That conclusion is borne out in the regression I described earlier, as well as this table, which shows how quickly the penalty idea breaks down once you control for something that is a more important factor than the Trump factor is. That said, it does seem that the penalty was real for challengers and those running in open seats when their district was the primary one in their media market.

One of the problems with the Trump penalty story is that it presumes that voters were fully aware of whether Trump had endorsed particular congressional candidates or whether the Republican House candidate in their district was a denier. This becomes apparent when we look at how many CD’s are in the media market that serves each Cook race. When basically the Cook race is the only one being covered in the media market, the penalty soars to 9.5 points. But once there are more than two CDs in the media market, it drops to 1.5 points.

Indeed, it’s hardly credible that if no one seemed to know that Santos was a pathological liar that everyone knew whether the Republican congressional candidate was a denier.

Candidate Quality and Other Campaign-Specific Explanations

Campaign-related elements can’t explain the larger trend of the Blue Undertow. While I think many of the Republicans on the ballot were batshit crazy and knew nothing about how to run campaigns, it is also true that (1) if you ignore the substance of her crazy claims, Kari Lake was a much better candidate than Katie Hobbs on whatever scale political savants would have rated them before this cycle, and (2) that Republicans lost many down ballot races in which most voters barely knew anything about either candidate.

I think some Democrats ran excellent campaigns, but it made the equivalent difference of kicking an extra point (or maybe a two-point conversion) whereas the salience of MAGA scored the touchdowns. Think of Arizona, where Hobbs won by 0.5 points and Kelly by 4.9 points. Superior Democratic campaigns meant keeping more MAGA Republicans from office (which is crucial for our future hopes), but they don’t explain at all why the Blue Undertow bucked the routine midterm rout of a president’s party in a cluster of specific states.

The Chopping Block

Some opinionators are as ruthless as Procrustes in cutting off evidence that tells a different story about America than the one they are accustomed to telling. For example, to the extent “gerrymandering” is even mentioned in midterm analyses, it’s to assure us that it didn’t matter. Here I want to provide two more examples of factors that have been ignored or misrepresented by Procrustean punditry - differential partisan turnout and Black voter participation.

Differential Partisan Turnout

If Democrats did better in the MAGA Statewide Competitive states because Independents and Republicans either split their tickets or skip the congressional ballot line, we would not expect to see much variance by region or candidate type when we look at the number of votes cast as a percentage of 2020 presidential votes. But, if the primary driver is turnout, we would expect to see no, or small, difference in 2022 Republican House Republican votes as a percent of 2020 Trump votes between MAGA Statewide Competitive states and the other states, but big differences for Democrats in the same statistic.

In the 150 closest districts, we can see that there was almost no difference between the two regions in the percentage of Trump votes that House Republicans received, but the difference was enormous for House Democrats. In the MAGA Statewide Competitive states, despite the historic trends to the contrary, Democrats received nearly the same share of Biden votes as Republicans received of Trump votes. But in the other states, we see what we see every midterm – a big drop off in votes for the president’s party (10 points in this case!).

Now, let’s look at the same variables we looked at for the presidential swing regression earlier, except this time we will look at them with regard to the percentage of total votes cast in 2020 (for both House Democratic and House Republicans), votes cast for Biden, and votes cast for Trump.

There are at least two very important things to see here:

There is a very strong relationship between region and turnout for total votes cast, and for votes cast for Biden, but not for votes cast for Republicans. This is another way of confirming that what happened in the MAGA Statewide Competitive states was mostly a matter of more Biden voters showing up relative to other states.

The most powerful factors are ecological, not campaign specific. Again, if swing voters were increasing Democratic vote share in particular districts, we would expect to see the same overall turnout, but lower turnout for Republicans.

Black Voter Participation

In late November, the New York Times’ Tilt ran a piece called “Black Turnout in Midterms Was One of the Low Points for Democrats,” which included this graph:

He goes on speculate on why that might be:

Still, relatively low Black turnout is becoming an unmistakable trend in the post-Obama era, raising important — if yet unanswered — questions about how Democrats can revitalize the enthusiasm of their strongest group of supporters.

Is it simply a return to the pre-Obama norm? Is it yet another symptom of eroding Democratic strength among working-class voters of all races and ethnicities? Or is it a byproduct of something more specific to Black voters, like the rise of a more progressive, activist — and pessimistic — Black left that doubts whether the Democratic Party can combat white supremacy?

For the moment, let’s put aside the fact that low Black turnout should be a “low point” to any of us who care about having a legitimate government or healthy society, not just to Democrats. The piece doesn’t even consider or mention the fact that in the time period he graphs, the Supreme Court (beginning with Citizens United and Shelby) and state legislatures have steadily made it more difficult for voters of color to cast a ballot. Since the Shelby ruling allowed states to pass laws that would likely have been struck down by the Voting Rights Act, more than 100 laws have been enacted in the predictable states to make it more difficult for people of color to vote, or for their votes to be counted. Not to mention the expiration of the consent decree against RNC for its Ballot Security Task Force voter suppression activities, or the proliferation of voter suppression organizations, election police in Florida, and more. There’s not even a recognition that last April, a major Times’ piece accused Democrats of exaggerating the effects of voter suppression (“Georgia’s Election Law, and Why Turnout Isn’t Easy to Turn Off”).

This isn’t to say that I think voter suppression is the only reason Black turnout was so low in 2022. But failing to even consider it as a factor is a classic, and inexcusable, Procrustean omission.

How Procrustean Punditry Poisons Our Politics

When they explain our politics, Procrustean pundits hack off nearly every factor that could cast doubt on the myth that at the end of the day, our democracy always fully represents the consent of the governed. These factors include:

Voter turnout. In this last election, all we heard about was the decision making of the roughly 11 million swing voters who experts consider “swing voters,” but almost nothing at all about the at least 45 million Americans who voted in 2020 but not in 2022. Experts implicitly assure us that we don’t need to pay attention to those who don’t vote, because we “know” that they would vote in exactly the same proportions as those who actually cast their ballots.

Rules changes. Before elections, we can discuss endlessly how different election law changes would advantage one or another party, but it’s taboo to talk about those rule changes after the election unless it’s to disprove that those changes affected the outcome at all.

The role of money in politics. We can wring our hands about how much money there is in politics, but after elections we have to fall in line behind the unsubstantiated assumption that in the end, spending on both sides will cancel out so that magically, whomever we elect would still have been elected if there were no money in politics, and they would govern as if there were no money in politics.

Media coverage. While we are ready to attribute outcomes to campaigns’ advertising decisions, and study ad buys meticulously, it's an embarrassing apostasy to suggest that what the media covers matters – such as, for instance, counting how many “points” of relevant political information the media broadcasts in the same way we study paid ads. Never mind questioning the expiration of the Fairness Doctrine or the de facto elimination of constraints on media empire building.

We are saddled with an expert class of opinion leaders – serious journalists, political operatives, and issue advocates alike – who chop off any evidence that politics has profoundly changed in the Trump Era. This trend is as debilitating to the health of our politics as would be climate forecasters who refuse to incorporate carbon levels in their models because those models do such a good job of explaining the last few millennia. We cannot adequately defend ourselves against the rising threat of MAGA fascism when the people who most shape our political narratives fail to tell the truth about it.

Appendices

Table of Appendices

Appendix I: A New Turnout Era

Appendix II Midterm Dynamics

Appendix III: Ticket Splitting

Appendix IV: Messed Up Exit Polls

Appendix V: Regular Voters are not Like Other Americans

Appendix I: A New Turnout Era

Since Reconstruction, turnout rates have varied little over long stretches of time, excluding the elections immediately after first women and then 18 year olds were given the vote (when the denominator grew suddenly) and during World War II. But historically, elections in which turnout rates suddenly increased or declined by more than 5 points have signaled the beginning of a period in which turnout remained stable, but at either a higher or lower level than before.

Because turnout rates were so stable it seemed obvious that when party fortunes changed, it was because the voters who had voted in the last election changed their minds. Only when voter files became available could we properly understand the role turnout plays in midterms.

In 2016, Clinton won the national popular vote by 2.2 points. According to the Catalist analysis, Biden won those who voted in 2016 by 1.5 points, 0.7 points less. Panel studies generally show that among 2016 white voters, net vote switching favored Biden, while among voters of color, the opposite was true.

Biden broke even among Prior Voters, but won by substantial margins with New Voters – by 9.8 points among 2016 New Voters, 16.7 points among 2018 New Voters, and 9.8 points among 2020 New Voters. (The “9.8” is a coincidence, not a typo.) The second set of bars summarizes that Biden won by 1.5 points among those who had voted in 2016, and by 11.7 points with Trump Surge Voters.

Appendix II: Midterm Dynamics

Had 2022 been an ordinary midterm, Democrats would have likely lost at least twenty seats and their Senate majority as well as their House majority. Democrats would also likely lose executive control in at least Wisconsin and Pennsylvania. Going into June, 2022, all of the reliable midterm indicators were pointing towards Democratic doom, including presidential approval, the general congressional ballot, Democratic underperformance in special elections, significant across the board erosion in the scheduled 2021 elections, most notably in Virginia, significant retirements, as well as economic anxiety as prices steadily rose.

Often, midterm elections are driven very much by differences in partisan turnout. This can be illustrated by using the voter file, along with partisan modeling, to understand what happened in the 2014 midterms.

In 2012, House Democrats won nationally by 2.1 points. They lost the national vote two years later by 5.4 points, a swing of 7.6 points. As the chart shows, 6.1 points was the result of far more Obama than Romney voters not voting in 2014. Only 0.9 points of the drop was because of 2012 Democrats voting for Republicans in 2014 – we are in an era where very few voters switch.

This is the dynamic every midterm, and why, since the House expanded to 435 members in 1914, only three presidents have gained seats. Almost by definition, the party winning the presidential race benefits from greater enthusiasm, meaning that they were better able to turn out less regular supporters. Having won the presidential race, those voters relax – and paradoxically, see the incumbents’ expressions of confidence and success as reasons their votes are less necessary. On the other hand, those who voted for the losing side in the presidential are aggrieved and powerfully motivated to stave off what they see as existential danger. Republicans are now motivated the way Democrats were after Trump won.

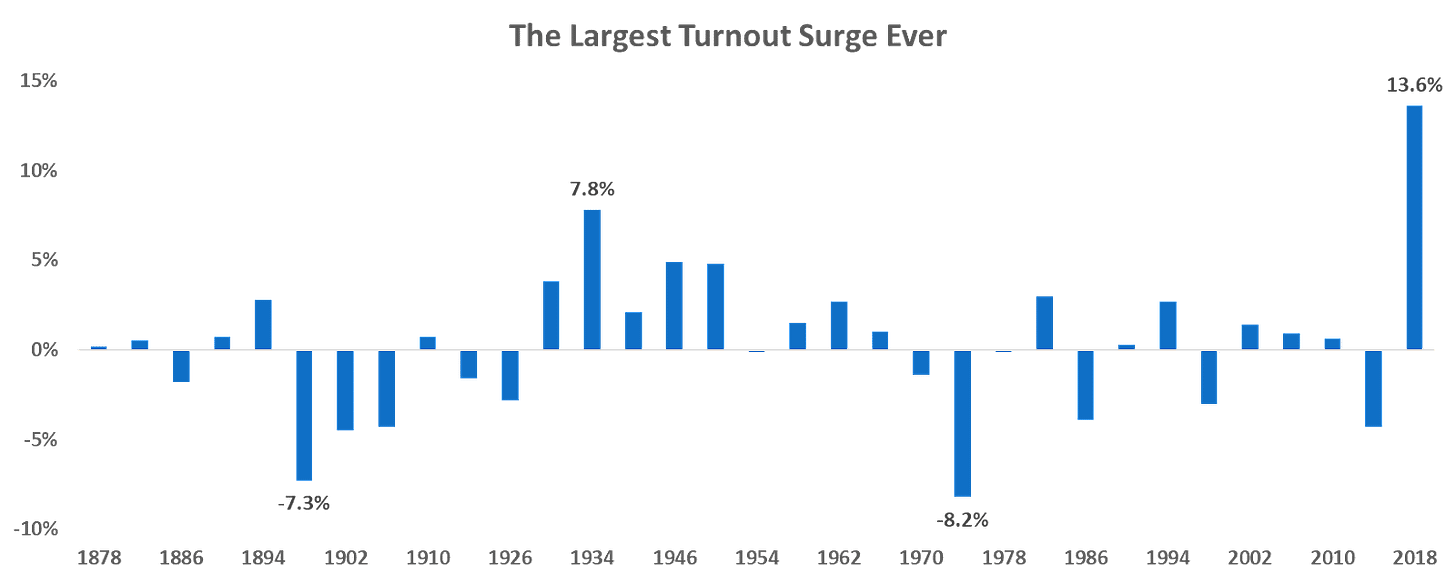

Midterm turnout rates have been one of the most dependable constants in electoral politics. Before the 2018 midterm, turnout had increased by more than five points only once in the previous 140 years.15 And in the eleven midterms since the voting age was lowered to 18, turnout was no lower than 37 percent and no higher than 42 percent, a mere 5-point range, and never increased by more than 3 points from one midterm to the next. And then this happened:

Given the turnout rates since the Civil War, the binomial probability of a 13-point increase is 1 in 500. In other words, voting has changed. As I explained in Appendix I, turnout for both midterms and presidential elections has stayed within very narrow bands for extended periods of time. In fact, unless you got your start in politics before 1972, you have lived in only one midterm turnout era.

Now, let’s look at what this means about how we should think about the 2022 midterms. The best way to understand the Democrats’ challenge is simply as ensuring that as many of the 81 million who voted for Biden return, and that as few of them as possible defect.

Before 2018, the pool of voters who voted in midterms was Republican leaning. And, among those who voted in both 2020 and the 2014 midterm, Trump had a 3 point margin. What makes the 2018 midterms extraordinary is that two new groups of voters showed up – those who had been voting in presidential elections but not midterms, and those who had not been voting at all. Both groups heavily favored the Democrats – the former group by 11 points, the latter by 19 points.

Those two groups of new Democratic midterm voters – those who previously only voted in presidential races and those who had not been voting – amounted to 25 million people, nearly as many as regular midterm voting Democrats.

To sum up, in 2018, 25 million Biden voters showed up who had not voted in midterms previously, a 13-point advantage over Trump voters who voted in the 2018 midterms. Furthermore, it’s crucial to understand that this surge in Democratic support was hardly limited to “base” areas – it was spread across all geographies.

Appendix III: Ticket Splitting

In some high profile states, it was obvious that some voters cast their ballots for one party for governor and another for the Senate, which some argue constitutes incontrovertible evidence that campaigns and candidates matter because there are so many swing voters.

A second tranche of evidence for the role of swing voters is ticket splitting. This can seem incontrovertible when we hear about wide differentials between candidates. Let’s take a look at two widely cited examples, Arizona and Georgia, where this kind of chart seems to make it look like both states had a very substantial amount of ticket splitting. Based on this, we think that about 2.2 percent of Arizona and 4.3 percent of Georgia voters voted for Lake and Kelly or Kemp and Warnock.

But, now let’s take a closer look at who voted for which candidate, first in Arizona. The chart below breaks the 2.6 million people who voted in the governor’s race into four categories. Obviously, the largest two categories are those voted for either Lake/Masters or Hobbs/Kelly. But this lets us see that about 40,000 of those who voted for Lake skipped the Senate line, while about 34,000 who voted for her voted for Mark Kelly. Thus, only about half of the naive ticket splitting was actual ticket splitting.

Now, let’s look at the same thing in Georgia. Here we see that about 71,000 Kemp voters skipped the senate ballot, and about 132,000 voted for Warnock. Thus, only about two-thirds of the naive ticket splitting was likely actual ticket splitting. And to be clear, 132,000 ticket splitters amounts to just 3.3 percent of those voting for governor in Georgia. And that’s the most prominent example of ticket splitting.

The ticket splitting illusion is worst in down ballot races, where ballot roll off16 accounts for an even greater share of apparent ticket splitting. Unfortunately, it will be a while before we have a clean data set with the top of ticket votes cast by down ballot jurisdictions.

Appendix IV: Messed Up Exits

Once again, the Exits were disastrously wrong, and therefore so were the early takes by commentators who should have known much better. Since VoteCast is generally considered to be the superior exit poll, I’ll just deal with theirs.17 Election week, they had Republicans winning by 5.2 points. With nearly all the votes counted, and available at the Cook Political Report with Amy Walter here, the margin stands at Republicans by less than three points. Democrats routinely gaining several million votes in the week after the election has always been foreseeable, and even has a name, “blue shift.” The biggest reason is that the West Coast states vote by mail, and take more than a week to count mail ballots.

Additionally, because national margins are easily distorted when one party has more uncontested seats than the other, analysts routinely adjust to reflect what would have likely been the case if those races had been contested.18 When that adjustment is made for this midterm, the final national margin is going to be no more than 2 points.

In other words, the Exits were weighted to an outcome that assumed Republicans won by about three times the margin they actually won by.

Here are the implications of the exit polls having been (as usual) wrong:

Democrats didn’t really win more seats than votes, as Charlie Cook and others claimed. If the actual margin is 2 points, Democrats should have 49 percent of the seats in the House, or 213.

Trump voters were not 2 points more of the electorate than Biden voters, and those who hadn’t voted in 2020 were not 16 percent of the midterm electorate, undercutting the algebra David Shor and others used to claim this was a “persuasion” election.19

And hot takes about demographic groups via the Exits are even sillier than usual:

Since the Exits are used to weight the entire survey to what they think the outcome is, each subcategory is off in ways that can’t be anticipated. (For example, white non-college.)

Exits have large margins of error, so making a trend comparison with the 2020 Exits for any one demographic will have at least twice the MOE you think it does.

And even if the Exit data were accurate, when applied to any demographic analysis they are incomplete because of what I’ve called, “never the same river twice.”

Appendix V: Regular Voters Do Not Look Like America

According to the US Election Project, going into the midterms, there were 239.5 million American citizens eligible to vote (CVEP). According to the Catalist voter file going back to 2008, about one-fourth have voted in the last 4 elections. (That is, voted in 2014, 2016, 2018 and 2020. I’ll shorthand them “4/4” in the text.) As many as another 63 percent of CVEP are not 4/4 voters but have voted in at least one election since 2012. Meaning that while most think of only about two-thirds of Americans as “voters,” in fact about 88 percent of those eligible have voted in the past decade. And, not surprisingly, there is wide variation by race.20 (This table breaks down each race/ethnicity by its vote history, thus percentages are column percentages.)

In the next chart, we can see the racial breakdown of each vote history cohort. Here, we see that while whites are 68 percent of the eligible population, they constitute 80 percent of those of 4/4 voters and only 25 percent of those who have not voted. (Here percentages are row percentages.)

Not surprisingly, older voters are a much greater proportion of Regular Voters than they are of the electorate - Boomers and older constitute 58 percent of Regular Voters but just 43 percent of the electorate.

And, finally, Regular Voters are more likely to have a college degree.

Competitive based on the final Cook Report with Amy Walter ratings. Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Georgia, Kansas, Maine, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin constitute the MAGA Statewide Competitive states.

The political science idea that basically parties who win elections go too far and voters use the next election to reign them back.

CVEP is the acronym for those eligible to vote. In 2022, the US Election Project estimates that to be 239 million Americans. This is different (and obviously smaller than) the more widely reported VAP (Voting age population) or CVAP (Citizen Voting Age Population) produced by the Census Bureau. Voters: Those who cast ballots. In 2022, the US Election Project estimates that 111 million Americans cast ballots. This number is always greater than the total casting ballots for any particular office.

I am very intentionally calling it “differential partisan turnout” and not “mobilization” because the terms “mobilization” and “persuasion” have become proxies for fraught ideological positions about campaign strategy. Since this is an analysis of what the voters did, we can only accurately talk about vote switching and turnout, both of which happen with and without interventions by candidates or political organizations. For more, see the Appendix.

And Alaska since the one CD is a statewide election too.

Although I generally eschew the Exits for reasons I’ve elaborated on elsewhere, it is very much worth noting that the VoteCast results confound even those who have been relying on them. Importantly, the results I show above – that there was very little if any partisan defection in House voting that favored Democrats – is consistent with both New York Times/Sienna surveys and all the pre-election surveys I saw.

By that I mean they either literally did better than they had in 2018 if they were seeking re-election, or did better than the Democratic candidate in 20118 if it wasn’t them.

It makes much more sense to differentiate between competitive races and others, as Nate Cohn and others properly have. If nothing else, it assures that voters are more likely to know whether the Republican candidate is a denier. Many have used the Cook ratings to define “competitive” races. I have chosen a more objective set based on the final results – the 150 closest races, all of which were within 20 points. There are three important reasons for doing this: (1) For greater statistical significance. With only 88 Cook competitive races and a 2 region x 2 type of candidate framework, that’s only about 20 cases in each cell, which could make the cells too sensitive to one race (although in fact, that didn’t matter much); (2) To show that the effect extends beyond the most competitive races, to further validate that the dynamics I’ve been describing are not only associated with the most competitive races; and (3) to enable comparisons across election cycles.

The actual Democratic margin in a jurisdiction minus Biden’s margin in the district in 2020 (2-way vote). The reason for using presidential swing should be obvious. Having won nearly every competitive election on the ballot in 2020, Democrats could have defended every incumbent simply by fully mobilizing and maintaining the allegiance of their 2020 voters.

This is very difficult to calculate precisely in earlier years, but this is broadly true.

I put Republican candidates into two categories by consolidating the FiveThirtyEight list, the January 6th roll calls to certify the Electoral College results, the Ballotpedia list of Trump endorsements, and Dave Wasserman’s classification of Republican primaries. The two categories are: (1) Deniers. Nearly all voted against certification on January 6th or were identified as deniers/Trumpy in one of those datasets. and (2) Others. Nearly all voted to certify on January 6th or publicly stated they fully accepted the results. Since the candidates for whom there was ambiguous, no or insufficient information available is small, and usually in lightly contested races, I rolled them in here.

That model incorporates polling and expert analysis as well as fundamentals.

My definition of regular voter: Either (1) voted in the previous four elections (in this case, 2014, 2016, 2018 and 2020), (2) voted in the most recent two or three elections if they were ineligible for 2014 or 2014 and 2016, or (3) voted in three of the last four if that includes the 2014 midterms.

This report reflects my analysis, and conclusions and do not purport to reflect the views, opinions, analysis or conclusions of Catalist LLC or any other entities.

This excludes the elections following the 19th Amendment when the denominator jumped and during World War II when the massive deployment of troops dropped turnout.

Ballot roll-off is the term used for those who turn out to vote, but don’t vote for every office. Most commonly, ballot roll-off looks like voting in just the top one or two races and leaving the rest of the ballot blank. If you think of “turnout” as applying to each individual race on the ballot, roll-off is really just another form of differential partisan turnout.

Unfortunately behind the Wall Street Journal paywall. Sorry

For example, in 2018, House Democrats won the counted vote by 8.4 points. But when you adjust, that comes down to 7.4 points. For obvious reasons, the 7.4 adjusted margin maps far better to the Democrats’ share of seats in the House, and national surveys, where those who would have voted for a Republican but couldn’t because there wasn’t one on the ballot, will still answer the survey question as if there were a Republican they could vote for on the ballot.

VoteCast estimated that 16 percent of voters (about 17 million people) had either not voted in 2020, or not voted for Biden or Trump in 2020. Compare that to the14 percent of the larger 2018 electorate (about 16 million people) who had not voted in 2016 for Clinton or Trump. Although we won’t know for sure the exact number until the voter files are updated in a few months, the idea that more people who skipped 2020 decided to vote in this midterm than those who had skipped 2016 decided to vote in the 2018 midterms is preposterous on its face. The problem is that it creates the illusion of more swing voters in the electorate than there actually were

For various reasons, the percentage of whites who have not voted is likely understated slightly.

Fighting an uphill battle here in Ohio to try and get progressives focused on the importance of turnout and, consequently, mobilization messaging. Here, election after election, the party and candidates seem determined to instead pander to the middle to win over swing voters with milquetoast messaging.

Would you consider digging into why Ohio fared so poorly in 2022 even with Vance on the top of the ticket? My take from on the ground in the state is that Ryan failed to sufficiently highlight his opponent's extreme MAGA nature, neither the coordinated campaign led by Ryan nor the party made an effort to excite and mobilize the progressive base, and lack of outside funding left the c3 and c4 groups without sufficient resources to take up the slack.

We have an urgent election in August to protect citizen ballot initiatives (and consequently abortion) and need to re-elect Sherrod Brown in 2024. But I'm not seeing that lessons have been learned.

Heard you interviewed by Dan P. So glad you are here writing.