The Limits of Education Essentialism

"Education polarization" is insufficient to explain the source of our political divides.

The idea that whether or not someone has a college degree is the best (or even a very useful) way to understand why people vote the way they do has quickly made “education polarization” a popular way to explain the behavior of white voters1 – and, increasingly, whatever else happens in politics. Its seeming incontrovertibility rests on the impression made by graphs like this one:

“Education polarization” has become something more than any other statistical association; it’s become the most prevalent response to questions like “What divides us?” or “How will Democrats fare in the future?” And it is being used as the intellectual scaffolding for arguments about the course the Democratic Party should chart. The problem with the above graph, and others like it, is not that it is inaccurate; it is that the story it is used to tell is dangerously misleading. Moreover, that story is increasingly crowding out understandings of our political predicaments that incorporate the central roles of race, gender, place, and class.2

Let’s remember that politics cannot be explained by a simple natural law, and certainly not by any kind of “unified field theory.” The truth is that no single concept can provide a simple explanation for the political behavior of 240 million people living such varied lives, coming from such different traditions.

The standard story of education polarization is expressed in the headline for the September 2021 New York Times piece where the above graph appears:

How Educational Differences Are Widening America’s Political Rift: College graduates are now a firmly Democratic bloc, and they are shaping the party’s future. Those without degrees, by contrast, have flocked to Republicans.

This shift, the Times’ story argues, isn’t just a neutral sorting process: College graduates have begun to “force the Democrats to accommodate their interests and values” because they “make up a disproportionate number of the journalists, politicians, activists, and poll respondents who most directly influence the political process,” alienating much of the Democrats’ traditional working-class base in the process.

This story seems plausible if you imagine, as many do, that “college graduate” = “liberal elite.” But under more careful scrutiny, the education polarization story starts to unravel. For instance, remember that a “college graduate” could have a degree from Harvard or from Liberty University; that enrollment in public universities is three times that of private universities; that less than 1 percent of college enrollments are at Ivy League schools; that there are about twice as many students enrolled in religiously affiliated universities as there are at Ivies; and that Ted Cruz, Mike Pompeo and Tom Cotton are Harvard graduates and Josh Hawley is a Yale graduate.

Education essentialists don’t offer a good explanation for why only Democrats would be pushed to the left by the college-educated elites in their ranks. After all, nearly all of the campaign staff in both parties have college degrees, and are more likely than other college-educated Americans to have attended more selective colleges.3 Right-wing political figures like Donald Trump (Wharton) and Brett Kavanaugh (Yale); media figures like Tucker Carlson (Trinity) and Laura Ingraham (Dartmouth); and activists like Steve Bannon (Georgetown) and Stephen Miller (Duke) are all college graduates. Thus, using a phrase like “college educated professional” does absolutely nothing to distinguish Democratic from Republican Party staffers. Saying “college educated professional staffers” is basically the same as saying “staffers.”4

Here is how this post will proceed:

1. What I am NOT saying. I need to make clear the aspects of what education essentialists say that are accurate.

2. Racial resentment matters more. Here, to make a point, I do what the education essentialists do – pick one factor to explain everything and show that this factor, racial resentment, does a much, much better job of explaining our current political divisions than education polarization. But the point is not to convince you we should substitute racial resentment for education as a monocause. That said, the graphs in this section offer many important insights into the racial politics of the last twenty years, which I give shorter shrift to than they deserve simply because they are not the focus of this piece.

3. Rinse and repeat. Here I pick a few other factors to illustrate how quickly controlling for other factors further diminishes the apparent importance of education polarization.

4. Structural defects. This is a bit more technical, but shows why education polarization cannot support the generalizations that it is often confidently used to make.

What I Am NOT Saying

Educational attainment influences vote choice. But many other things do so to a much greater degree, and particular combinations of those characteristics more so still. This post is not to deny that education level has any influence, but to make exceedingly clear that it is not a foundational block in any defensible system for understanding voter choice.

Educational attainment is a good heuristic when better data is not available, given its prevalence in administrative data and what is now routinely collected in surveys. If you’ve been following my writing for a while, you will remember that I have used white-education several times to make important points. For example, over the summer in 2020, when Biden was up by 8 to 10 points in most surveys, I pointed to the unexpectedly high rates of voter registration from white non-college voters over 30 relative to Democratic base groups, and then the same kind of disparity with respect to VBM application requests from those who had not voted in 2016 or 2018. That information, and similar kinds of administrative data, made it clear the polling was off by a couple of points, especially in the northern battleground states. “White non-college” is one of the most commonly available proxies for white Republicans.

A popular expression is, "All models are wrong. Some are useful."5 The point of this post is that a model or heuristic is “useful” only insofar as its specifications are not confused for explanations. Covariates of causes can’t be taken to be the causes themselves. In other words, the fact that I could use “white non-college” to accurately detect greater than recognized enthusiasm for Trump than was otherwise recognized did not convince me that people were voting for Trump because they were white and did not have a college education.

Racial Resentment Matters More6

I will be using American National Election Studies (ANES) data throughout most of this section because that is the data set used in the New York Times graphic.7 I am grateful to Ashley Jardina, associate professor of political science at George Mason University’s Schar School of Policy and Government and author of the acclaimed White Identity Politics, for doing all the ANES data runs in this section. (Alas, I am responsible for the quality of the graphics.)

The ANES racial resentment scale uses four questions to construct a racial resentment index8 (such as asking whether respondents believe that “if Blacks would only try harder they could be just as well off as whites”) and allows respondents to agree or disagree on a scale of 1 to 5, indicating their level of resentment. That index is unchanged throughout the entire period I’m looking at here. To visualize the effect of varying levels of racial resentment, we use quartiles to divide respondents below. Note that the quartiles are divided by levels of resentment and not by numbers of people; since Americans have become less racially resentful over the last 20 years, that means that there are now more Americans in the least resentful quartile than there were 20 years ago.

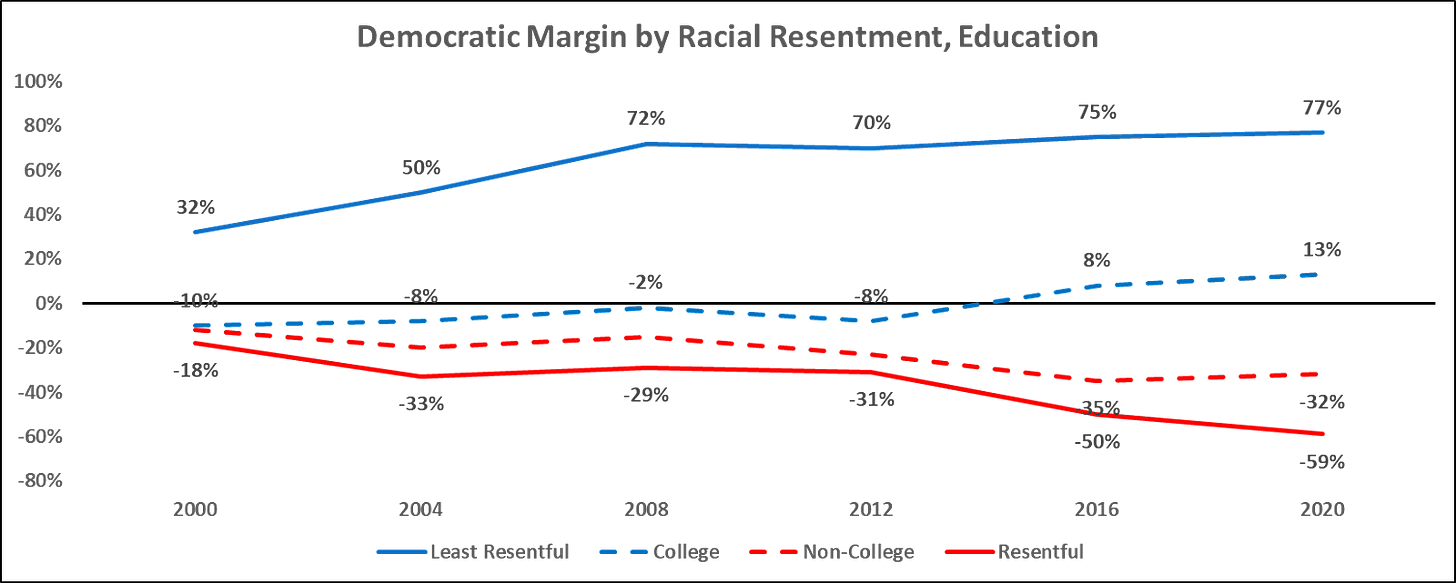

By 2000,9 the most and least racially resentful white voters had already substantially sorted themselves – Gore carried the least racially resentful whites by 32 points (66-34), while W Bush carried the most racially resentful by 38 points (69-31). (At that point, 18 percent of white voters were “least racially resentful” and 29 percent were “most racially resentful.”) Anticipating that some education polarization fans will say I’m cherry picking by singling out only the “most” racially resentful, I also show the three “resentful” quartiles (every quartile except the least resentful) combined on one line. The “resentful” quartiles put together are not different in shape from the most resentful quartile alone, and they track not much more Democratic than the most resentful. For the rest of the analysis I’ll be comprehensive, even though it would have more sensible explanatory power to look just at the least and most resentful quartiles.

By 2020, the gap had widened to truly shocking levels. Biden carried the least resentful white voters by 77 points (89 percent to 11 percent), and Trump carried the most resentful by 85 points, or 92 percent to 8 percent! (Remember that when I refer to "margins," I'm talking about the size of the gap and not the absolute percentage of voters who chose each party – as in, Trump won the most resentful by an 85- point margin.)

To fully grasp those big numbers, this is saying that the least racially resentful white voters were about as likely to vote for Biden as Black voters were, and that the most racially resentful white voters were even more likely to vote for Trump than white Evangelicals were. And, remember that by 2020, 38 percent of white voters were in the least resentful category, roughly equal to the percent that had a college degree.10

The least resentful voters were becoming steadily more Democratic until Obama’s election, after which they plateaued at about 9:1 (a likely ceiling effect). The most resentful, on the other hand, became more Republican against Kerry, but then plateaued through Obama, and then became more Republican still with Trump.

Now let’s add the college/non-college margins from the New York Times graph that has so many people convinced that education polarization is so important. Doing so makes it clear that the association between racial resentment and presidential vote choice has been much, much stronger than the association with education over the last two decades. Interestingly, the gap between the least resentful and the college educated became enormous by 2008 (74 points), while the 2016 election was the first election in which the gap between the resentful and non-college began to substantially widen. (The dashed lines reproduce the data in the New York Times’ graphic at the beginning of this piece and the solid lines reproduce the data in the just previous graph, so that you can see just how much more Democratic/Republican the least racially resentful/racially resentful are than college/non-college voters.)

Importantly, ANES allows us to look at racial resentment for college and non-college voters together. The next graph below divides college and non-college voters by their level of racial resentment. We can see that, for almost the entire period, educational attainment makes almost no difference for the least resentful and the resentful, while the difference within the education categories is enormous. The exception is that the Democratic partisanship of the least resentful non-college trails the least resentful college until Obama.

Now, to beat the horse that should never have been alive one more time. The idea that education polarization is driving the divisions in the country means that the most important metric would be the education gap – the difference in Democratic margin between college and non-college voters. (The same concept as the gender gap, applied to education.) The racial resentment gap (the difference in Democratic margin between the least racially resentful voters and the rest) was already larger in 2000 than the education gap is today, and, indeed, before 2000 college voters were slightly more Republican than non-college voters.

The difference between the education gap and the racial resentment gap is so large that this chart might be a bit difficult to process. We are not used to seeing numbers greater than 100 percent in conversations like this, and that’s my point about how unsubstantial the education gap is. Even the Black-White gap in Democratic margin is “only” 91 percent (Blacks +80 (90-10)) plus whites (-12 (44-56)).11

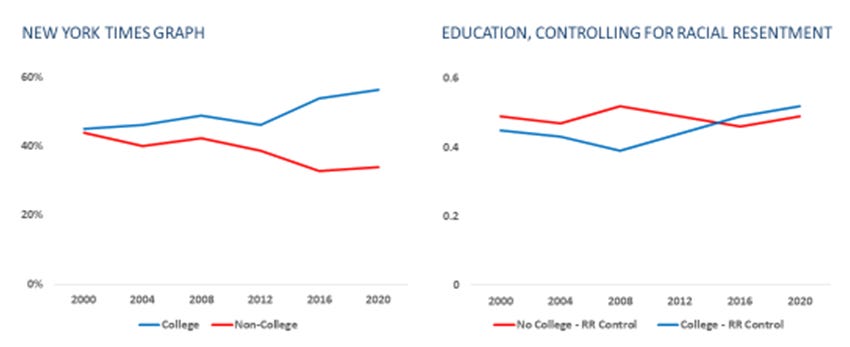

If you are still unconvinced, wondering whether the racial resentment gap merely reflects an association between educational attainment and racial tolerance, we can look at this question using regression analysis to control for each factor. In other words, educational attainment controlling for racial resentment, and racial resentment controlling for education.

The next two graphs do that. Two things come across dramatically. The first is that controlling for education makes almost no difference for racial resentment. Indeed, if we had not seen racial resentment without controls, nothing would change about how we viewed the association between racial resentment and Democratic partisanship. But when we look at education controlling for racial resentment, the result is dramatically different – not only are the associations much smaller, in some cases they are moving in different directions from one election to another.

Rinse and Repeat

To show that I’m not cherry picking racial resentment, consider the next two comparisons. The first is urbanicity. The color scheme is meant to show just how confounding it is to the education polarization assertion when we add urbanicity. Blue is college (the supposedly Democratic group) and red is non- college (the supposedly Republican group); solid is urban and dashed is rural. In other words, in urban and rural areas, college and non-college voters are more like each other than they are those with the same educational attainment in the other density area. Urban non-college in 2020 was D+18 while rural college was R+22. In other words, urban white non-college is almost a base Democratic group (59-41, while rural college is a Republican base group (61-39).

And, as Pew validated voter studies and PRRI surveys consistently find, the White Evangelical or white Christian gaps have always been larger than the education gap; white non-college non-Christians are a Democratic base group, while white college Evangelicals are a Republican base group.

Structural Deficits

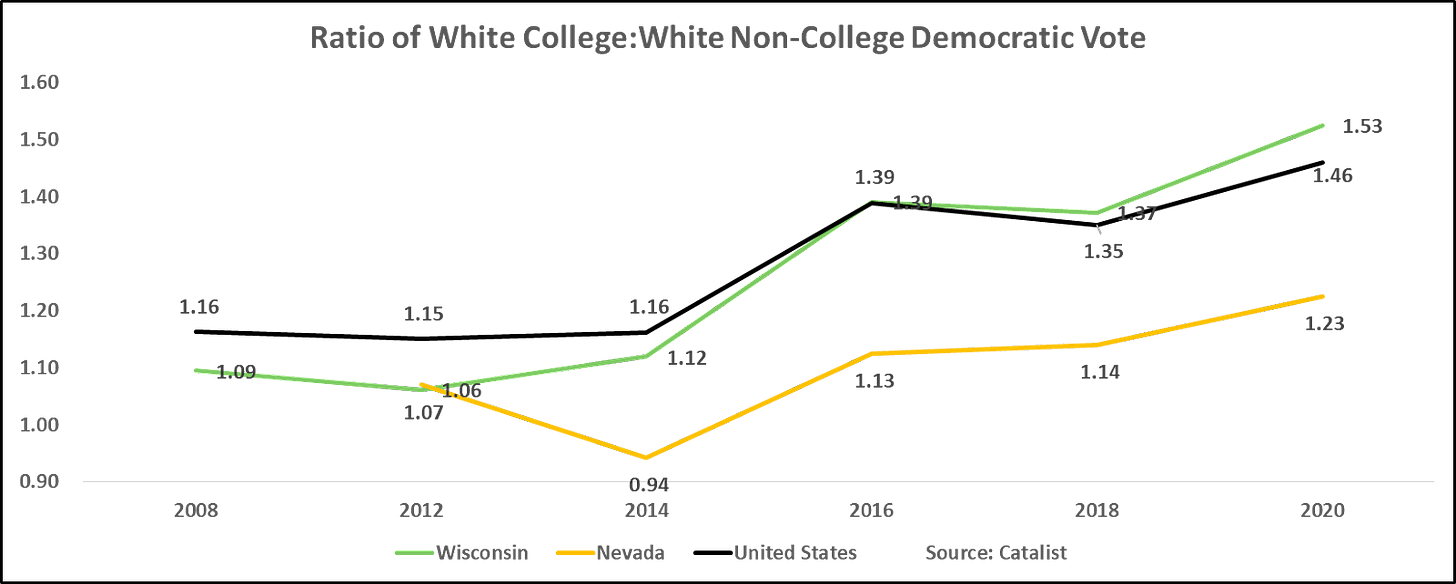

Here, we’ll look to see if the education polarization story has internal consistency. Especially because education essentialists assert that their perspective is essential to understanding Democrats’ dilemma at the state level, we should expect education polarization to look the same from state to state. Here we add two battleground states, Nevada and Wisconsin.12 If it looks confusing, that’s the point. Here we see that this big national trend actually breaks down quickly when you look at sub-national units.

Since education polarization is the relationship between the white college and non-college vote for Democrats, for a national trend to tell us anything precise the ratio in the states should be the same, or at least move in parallel in time. But here’s what it looks like.

Again, it’s not that there’s nothing there, but to rely on such a loose relationship to establish expectations about whether Democrats will win future statewide elections that will be decided by just a few points is insupportable. Which is why the notion embedded in a recent New York Times “power simulator” interactive – that merely by turning the national dial on the extent of education polarization, you could make sound forecasts of future Senate races – fails utterly. (And we saw that vividly in the 2022 elections.)

This last graph below makes a point so obvious that it becomes silly upon being brought to visualization. This shows just how slowly the percentage of the white population with a degree has been increasing, which belies this thesis in the original New York Times piece: “As they’ve grown in numbers, college graduates have instilled increasingly liberal cultural norms while gaining the power to nudge the Democratic Party to the left.” Since the 1950s, the share of whites with a college degree has increased by an average of ½ percentage point a year, and by more than one percentage point only three times – a glacial pace inconsistent with driving significant fluctuations from election to election.

Wrap-up

Let’s look at five criteria for considering something a solid foundation for a framework for understanding partisan voting behavior. Education polarization fits none of these criteria:

✘ Highly correlated with partisanship. Black (9:1 Democrat:Republican) and white Evangelical (4:1 Republican:Democrat) are strong. White college is, at best, 3:2 Democratic:Republican. Think about it this way: If all you knew about a voter is that they were white, you would guess they are Republican and be correct 56 percent of the time. If you could also know whether a white voter had a college degree, you would correctly predict their vote 60 percent of the time.13 That’s barely more predictive. Compare that with knowing whether a white voter identified themselves as Christian. In that case, assuming the Christians/non-Christians voted for Trump/Biden would be correct 67 percent of the time. And of course, even better, knowing whether or not they were least resentful would be correct 83 percent of the time.

✘ Connects to a significant self-claimed identity or group with strong exit constraints. No one claims non-college as an identity for themselves; most without a degree would be pleased if their children gained college degrees, and there really aren’t social networks organized around not having a degree in the way that is the case for, say, religion. An Evangelical would proudly identify themselves as such, listen to Christian programming, have enmeshed themselves in instrumental (e.g. day care) as well as spiritual relationships at their church, and would be aghast if their children left the congregation. And for most African Americans, not being seen as Black by others is not an option. Unfortunately, "identity" is not a category that is easily or consistently measured in surveys or administrative records.

✘ Connects to a sound theoretical framework. I’ve shown the extent to which educational attainment draws its value as a heuristic from its mild correlation with things like racial resentment. But variables like racial resentment and status threat represent well-researched and peer reviewed theories within social science, whereas the same is not true for educational attainment.

✘ Compositionally consistent. By that, I mean that there is no significant subgroup that has opposite partisanship. We saw this violated with urban non-college who are substantially Democratic. Likewise, non-Christian non-college.

✘ Supports generalizations. As we saw above, education polarization is not the same from state to state, either at a point in time or over time. Thus, generalizations about what would happen in state X if education polarization nationally is Y will consistently fail.

In other words, we have a dog bites man story. In the period we just reviewed,14 the Republican Party, and especially Trump, have been playing to white grievances, so it’s not at all surprising that those who embrace/reject white grievances are more likely to vote Republican/Democratic. Again, I do not consider racial resentment to be the only relevant - or even the best - explanation for our current political divisions – but the strength of that association, versus the weakness of education polarization, should make us question why we are spending so much time talking about the latter.

Let’s return to the original New York Times graphic, but now compare it with a graph showing Democratic vote controlling for racial resentment.15

Now, let’s return to the original headline:

How Educational Differences Are Widening America’s Political Rift: College graduates are now a firmly Democratic bloc, and they are shaping the party’s future. Those without degrees, by contrast, have flocked to Republicans.

Which we now understand would be better stated this way:

How Differences in Racial Tolerance Are Widening America’s Political Rift: The least resentful Americans are now a firmly Democratic bloc, and they are shaping the party’s future. Those committed to white supremacy, by contrast, have flocked to Republicans.

With regard to education, this post is concerned exclusively with white voters. Consider it implied if not stated every time. Recently, education essentialists have offered education as an explanation for the erosion in Democratic support among voters of color; this post does not deal directly with that. But, as should be clear by the end, education polarization claims are insupportable for voters of color as well.

In the political discourse, education polarization has almost completely crowded out the importance of identity, which has been substantiated in a steady stream of widely respected books published during the Trump years, including Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity (Mason), White Identity Politics (Jardina), Identity Crisis: The 2016 Presidential Campaign and the Battle for the Meaning of America (Sides, Vavreck, Tesler), Why We're Polarized (Klein) and The Great Alignment: Race, Party Transformation, and the Rise of Donald Trump (Abramowitz).

Shown by Daniel Laurison in his book Producing Politics: Inside the Exclusive Campaign World Where the Privileged Few Shape Politics for All of Us.

In Thinking, Fast and Slow Nobelist Daniel Kahneman provides marvelous examples of how most people, when they hear two descriptions of the same thing, with the only difference being that one has an additional true but irrelevant detail added, they over rely on their prejudices about the irrelevant information to make judgments. Anyone who pays attention to political commentary will be amazed by how it exploits the cognitive tics cataloged in Kahneman's books, or Bob Cialdini’s Persuasion and Pre-suasion.

Box GEP Draper NR. Empirical model-building and response surfaces. New York, NY: Wiley, 1987: Vol. 424

I want to be clear here that a measure of gender hostility would show the same kind of results. I use racial resentment in part because the data is handier.

Thank you to Nate Cohn for providing the series used in the graph.

There are critiques of the racial resentment measure, especially with respect to the meaning of “racial resentment.” However the same result is achieved with any question related to race. The purpose here is not that it is racial resentment in particular, but that it is racial attitudes, however measured, that are relevant.

Here, and throughout most of this section, I use 2000 as the starting point since (1) racial resentment was not on the 1996 ANES survey and (2) 2000 is where white college voters begin voting more Democratic than non-college.

If, in the wake of George Floyd, they were more aware of the “right” way to answer the questions, you would expect to see the partisan effect lessening. In other words, even though it was extremely socially desirable at that point to answer questions about racism tolerantly, if that were all, you would expect the momentarily woke to continue to vote Republican.

Catalist What Happened in 2020

These were handy - Catalist has released just those two states. But this is true regardless. There was no presidential vote for 2008 in the Catalist spreadsheet.

You would guess that the 61 percent of white voters who don’t have a degree would be Trump and the 39 percent of white voters with a degree voted for Biden. You would be wrong 37 percent of the time with non-college and 46 percent of the time for college. (Catalist What Happened.)

Of course, Republicans have been playing to white grievance for longer than this century, but we are focusing on the time since 2000 because of the consistency of data on racial resentment.

Note the New York Times graph shows Democratic share of the two party vote. For the graphs in this section, I’ve been converting that into Democratic margin, to streamline graphic comparisons. Here I convert back to Democratic share to compare with the Times’ graphic literally. Of course, there is no mathematical difference between margins and shares; the latter is always equal two times the former minus one.

So it would seem Fox News was ahead of the curve in identifying what drives Republican voters most reliably, and focusing as much of their coverage and commentary on stoking racial animosity and fear as possible.