Turns Out, Turnout Matters

…but only if you care about winning elections.

This article is the third in a four part series about the Pew report and common errors in conventional election analysis. Check out the first article, Confirmation Bias Is a Hell of a Drug, and the second article, All Politics Are Local; All Political Data Is National.

The big headline finding from the recent Pew validated voter study was that “Republican gains in 2022 midterms [were] driven mostly by turnout advantage”.1 That finding should remind us that in every election, voters have three choices – voting for the Democrat, voting for the Republican, or voting for neither (either by voting third party, skipping a ballot line, or staying home entirely).2 Yet nearly every story ahead of or after any election seeks to anticipate and then understand the outcome as if only the first two choices matter.

In this post, I want to do four things: show how turnout mattered in the midterms; offer a twist on the typical “Midwest diner” trope to illustrate the importance of turnout in this MAGA era; use the Pew data to show that Democrats have a turnout problem; and then dig into why talking about turnout has become almost taboo in the national political discourse.

How Turnout Decided the Midterms

There are actually two questions floating around about the midterms with accurate, but superficially paradoxical, answers:

Question 1 - Why did Republicans do better in 2022 than they did in 2020?

Question 2 - Why did Democrats do better than historical precedents and nearly universal expectations?

The Pew report only answers the first question clearly: Republicans did better in 2022 than they did in 2020 because in 2022, Republicans turned out more Trump voters than Democrats turned out Biden voters.

The answer to the second question is that in certain states, Democrats turned out far more Biden voters than historical precedents and universal expectations suggested they would. But as I wrote in my last post, All Politics Is Local; All Political Data is National, the Pew study can’t address this second question. That’s because Pew’s results are national, and Democrats’ overperformance was state specific.

In midterms, the president’s party always falls broadly short of its performance two years earlier. But, as I pointed out in Red Wave, Blue Undertow, and as Catalist observed in What Happened in 2022, in 15 states, the midterm results were altogether different from those in the rest of the country. In those 15 states, Democrats actually made gains, while the other 35 states saw the expected “Red Wave.”3

Pew also found that the “large majority of voters stuck with 2020, 2018 party preference in their 2022 vote choices.” As a logical proposition, it makes sense that if very few voters switched from their 2020 preferences, and the net effect of that vote switching on both sides was less than 1 point, relative partisan turnout would be the main reason that candidates fared better or worse in individual races. (Relative partisan turnout means the ratio of Democratic turnout rates to Republican turnout rates. That is how the Pew conclusion is expressed.)

So, it stands to reason that in states where Republicans did not have as great a turnout advantage as they did nationally, they would not do as well as they did nationally.4 Well before the voter files were available, this could be inferred from the raw results. Since there’s no real way to compare the turnout in a midterm to the turnout in a presidential election, I compared the 2022 turnout rate to the last midterm – 2018, which had the highest midterm turnout rate ever.5 In 2022, turnout remained just as high in those 15 competitive states as in 2018, and Democrats actually gained seats over their Blue Wave totals in those states. But you can also see that in California and New York, two deep blue states, Democrats lost twelve seats (and thus the House), and turnout was down substantially.

Now, with the voter file in hand, we can confirm this at an even more granular level by looking at turnout rates for Biden and Trump voters, respectively. As I’ve said, the key group to watch for this purpose is “new voters” who did not vote in 2016. According to Catalist data, outside of the competitive states, Trump voters turned out at about 6 points higher than Biden voters – but the advantage was half that among new voters in the competitive states. This is corroboration for the argument that Democratic “new voters” are motivated by the threat of MAGA Republicans.

Finally, with respect to the question of why Democrats did better than expected in the midterms, we have to distinguish between House races and Senate and gubernatorial races. It’s obvious that the margins of key statewide victories for Democrats in Arizona (governor and Senate), Georgia (Senate), Michigan (governor), Pennsylvania (governor and Senate) and Wisconsin (governor) benefited from both higher than expected Democratic turnout and net vote switching. But in the House, which is the focus of the Pew report as well as this post, turnout, not vote switching, clearly drove Democratic overperformance in these states.

Turnout in the Time of MAGA, Seen Through A Midwest Diner

Since 2016, if not before then, say the words “white non-college voter” or “Midwestern swing voter,” and you can’t help seeing a burly guy in a diner. We’ll call him Bob. You know Bob’s life story without being told – he worked hard all his life and played by the rules. He used to be a Democrat, and he voted for Obama. But now, as good jobs disappear and prospects for his children dim, he’s troubled that Democrats don’t seem to care or have anything to offer him. It wasn’t always that way. He always thought Rush Limbaugh made a lot of sense, but some of his hunting buddies (who were in unions) convinced him to give the “Black guy” a chance. Now, Bob is convinced the Democratic party is run by coastal elites who condescend to people like him – men who still believe in the traditional values that made America great. And there’s no one he trusts to tell him otherwise.

Bob represents the way the media thinks about politics. As Bob goes, we are told, so go white non-college voters, Wisconsin, and the Electoral College.

But, if you think Democrats can’t win Wisconsin without Bob’s vote, let’s revisit that scene in the diner, letting the camera pan out. Immediately, we’d see Charlene leaning over the counter to pour Bob’s coffee. She voted for Obama both times but skipped 2016 because she didn’t see the point. Since then, she has been ambivalent about Democrats, but she doesn’t want to see Trump back in office.

Pan left and you will see Jimmy, Jenny, and Amber in a booth by the window. They’re in their twenties but couldn’t afford to go to college. They still don’t have full time jobs (let alone hopes for a career), and they have to piece together two or three gig jobs to get by. They don’t think that politicians can help them, and they think Biden is too old. But, especially after Dobbs, they don’t want any more of their freedoms snatched from them. On their social media, they see nothing but ridicule and scorn for the Orange One.

With all those folks in the picture now, you should begin to see how Biden won Wisconsin in 2020, and Tony Evers won by even more in 2022 (a “red” year) than he did in 2018 (the “bluest” midterm since Watergate).6 Neither Biden nor Evers won over Bob – but first Trump and then MAGA were serious enough threats that two of the other four, who had rarely voted before, are voting now. (Of course, voters who look like these five people are only one piece of the puzzle; the repercussions of Trump’s election have scrambled many partisan allegiances and participation rates across the demographic landscape.)

In 2024, Bob can be expected to vote for Trump – he always votes. And Charlene will likely vote for Biden. There’s no chance the Gen Z’ers in the booth will vote for Trump, but whether Biden wins the state will depend on how many people like the Z’ers in that booth – and others across the state who have just recently begun to cast ballots – decide to turn out. And, if they do, it won’t be because ads have convinced them to reward Bidenomics; it will be because they, along with many of their friends and social signifiers, will catch the fall flu – a mostly unspecific, but widely shared sense of dread that, yes, things would be worse if Trump came back.

Before we leave them, remember that every time Bob, Charlene, Jimmy, Jenny, and Amber show up in political stories, they all occupy the same single banner book cell: “white non-college voter.” Every time you read someone “explaining” politics or advocating for this or that policy on the basis of what white non-college voters want, they mean what Bob wants, and they are counting on you to ignore Charlene, Jimmy, Jenny and Amber. And they are ignoring completely the question of who will vote.

Most Americans Reject MAGA. Will They Vote?

Throughout 2022, national polling trends brought fevered speculation about whether Democrats were losing key demographic groups, like Latinos or voters without a college degree, and analysis since has echoed these worries. But none of those polls could tell us about the key element that we needed to know then, and that will decide the election in 2024: how many people who support Democrats (or hate MAGA) will actually turn out to vote.

Another virtue of the Pew reports is that they do provide information on those who do not cast ballots. Pew finds that those who support Trump and MAGA have been turning out at a higher rate (but not always in higher numbers) than those who oppose them. In 2020, according to the US Election Project, there were 240 million Americans eligible to vote, of whom about 155 million voted for either Biden (81 million) or Trump (74 million). In its validated voter study for both the 2020 and 2016 elections, Pew also reports on the presidential preferences of those who did not vote. Here’s what they found:

The striking difference between 2016 and 2020 was the change among those who hadn’t voted. We can see that two things happened to those who had not voted in 2016:

Non-voters decided that there was more than a dime's worth of difference between Trump and the Democrats. In the graph above, look at how much taller the “non-voters'' bar is in 2020 than in 2016. That’s because in 2020, the share of non-voters who wouldn’t indicate a candidate preference (who aren’t shown in the graph) dropped from a full third (33 percent) to just 15 percent. In other words, the experience of the four Trump years more than cut in half the share of non-voters who had no preference between Trump and the Democratic nominee (Biden or Clinton). And that shift very much favored Biden, taking the non-voter margin from Clinton +7 points to Biden +15 points.

A disproportionate share of 2016 non-voters who came off the sidelines came out to vote against Trump. (This is just an independent way to get to the central argument of the emerging anti-MAGA majority – this time through Pew’s polling; above it was through the voter file.) And, even with more of the 2016 non-voters voting for Democrats in 2020, the margin against Trump among the remaining non-voters increased.

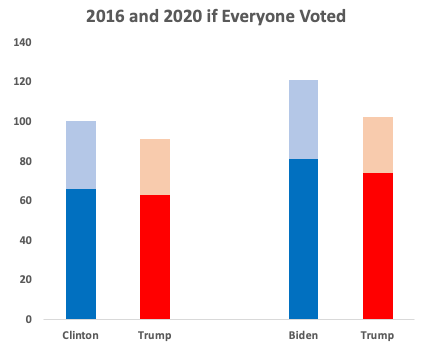

Consider this thought experiment. The following graph shows what the 2016 and 2020 elections would have looked like if everyone who expressed an opinion to Pew had also voted, with the dark blue and red representing how people actually voted and the light blue and red representing those who did not vote. If the nonvoters had turned out, both Clinton and Biden would have defeated Trump decisively.

Now, let’s take this calculation a step further. In 2016, Clinton’s 65.9 million votes represented 66 percent of those who either did vote for her, or told Pew that they would have. But Trump’s 63 million votes represented 70 percent of those who did or would have voted for him. It’s a glass half-empty or -full question to ascribe Trump’s higher turnout rate to his own appeal or to Clinton’s lack of appeal. I’m inclined to ascribe it to the latter, though, in light of both the turnout rates in previous elections and the fact that Trump ran behind House Republicans.

Now, if we fast forward to 2020, using the same logic, we can see that the turnout rate for Trump supporters rose by three points to 73 percent, while the rate for Biden supporters increased by just a point to just 67 percent. Thus, the turnout gap grew from 4 to 6 points, as the next graph shows.

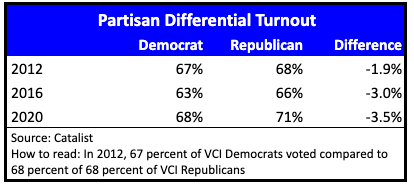

It’s always best when addressing these kinds of questions to find independent approaches to see if similar conclusions can be reached. To do that, we’ll look at the same question using the Catalist voter file instead of polling. Catalist scores every record on its file with what they call Vote Choice Index (VCI), which is intended to rate the likelihood of that voter having voted for a Democrat. VCI is much more accurate than traditional polling-based modeling because scores are normalized to the actual votes cast in each precinct. Although not specifically intended to, the VCI scores track House Democratic performance more closely than they track presidential, but obviously the two are close.

Now, after all that windup, what we find are very similar results, but we can also compare it to 2012. This data shows a partisan turnout differential as well, and shows it increasing over the last three cycles.

Why We Don’t Talk About Turnout

Despite its obvious importance, turnout is simply not a dynamic that the political press (or most academic researchers) pay attention to. It’s not easily predicted, which means it’s hard to use to speculate about electoral outcomes (especially when those elections are more than a year away). Every election, exit polls rush to tell us why the people who cast ballots voted for Democrats or Republicans – but no attention is paid to why those who didn’t cast ballots skipped the election, or for whom they would have voted if they had cast ballots. That is especially egregious for the recent midterms, as, again, we know that 45 million people who had voted two years before stayed home.

Casting a ballot is a behavior, not an opinion. If you are not a campaign practitioner, the significance of that difference is likely not at all apparent. Here’s how I think about who votes in elections:

Regular voters. They can be expected to turn out in every election regardless of who or what is on the ballot; it’s habitual for them.

Presidential voters. They can be expected to vote in presidential elections, but rarely turn out for other elections. They voted in 2016 and 2020.

New voters. These are voters who did not vote in 2016, but have voted in at least one election since.

Eligible voters. These are the remaining Americans who are eligible to vote but haven’t. About half are registered to vote.

There are about 72 million people in the first group. If turnout is as high as it was in 2020, they will make up less than half the electorate. And they lean Republican by about 3 points. There are another 10 million presidential voters. If they all vote in 2024, they’ll be about 5 percent of voters, and they lean Democratic by about 4 points. If only those two categories of voters cast ballots in 2024, Republicans would win by about 2 points. Sit with this: We can expect a bit more than 90 percent of those folks to vote, and if they are the only ones to vote in 2024, Republicans would win the popular vote as well as the Electoral College.

But there are another 70 million Americans who have cast only one or two ballots in the last four elections. They are a very Democratic group – about +12 points. They include four of the white non-college voters we met in the diner (Charlene, Amber, Jimmy and Jenny), as well as voters from other demographic groups.

Behavior is much trickier to track and write about than opinions. Polling at its best can only measure opinions. Thus, generating what seem like plausible inferences about partisan choice is fairly inexpensive. Methods to anticipate behavior are more expensive and don’t lend themselves easily to point estimates. And worst of all, the most important factors influencing the behavior of those who don’t vote habitually are not manifest until closer to the election.

All of that helps explain why it’s much more difficult to write stories about expected turnout than it is to write stories about the trial heat in the latest survey. But it still doesn’t explain the intensity of the efforts to convince us that turnout doesn’t matter, and the consequent disinterest by the media in those voters who skip elections.

I think turnout has become taboo for a few reasons:

Ideology. Especially since 2016, when Clinton’s loss was blamed on her reliance on identity politics, “turnout” has become code for those who want Democrats to embrace bold left ideas to rally disaffected voters, and “persuasion” has become code for those who want Democrats to move to the center. Analysts committed to this centrist approach have worked extensively to dismiss as unserious the idea that Democrats would win more elections with greater turnout. Unfortunately, this ideological baggage can make it difficult to use the word “turnout” as a straightforward technical descriptor.

Civic virtue and democratic myths. As a society that prides itself on being the “oldest democracy,” it’s uncomfortable to acknowledge that turnout rates in the United States are subpar in any international comparison.7 Moreover, we don’t want to acknowledge that we would be a different country if everyone voted. Until 1965, the best we might honestly claim is that our elections established the consent of white Americans. There is obviously a lot more to say along these lines, but in this way, as well as many others, elections are reported on and studied in frameworks that presume that democracy works the way our myths tell us it should. Along those lines, note that campaign spending almost never comes up in political reporting outside the context of how many dollars are raised or spent. We hear little about where that money comes from or whose interests are served by those donations, even though certain industries and interests spend billions of dollars to influence our legislative and judicial processes. Indeed, despite incredibly easy access to data about who is financing our elections through OpenSecrets, we only hear about money in politics in savvy stories about which candidate or party is raising more, as if doing so should be a credential for winning office.

There’s more to it than this, of course. In particular, there are other factors going on for those who a) honestly don’t know the difference between polling and politics, b) try to come up with fresh hot takes when there are none to be had, and/or c) try to get clicks for themselves by offering “data driven” insights from the sidelines or bashing Democrats for not agreeing with them.

Conclusion

The Pew report aligns with pretty much every poll taken since 2016, including the most recent one by the New York Times, in that it shows that a vanishingly small number of people who have voted for either Biden or Trump are having a change of heart. This means that to a truly unprecedented extent, election outcomes are now predictably determined by partisan turnout rather than by the extent to which Americans switch their voting allegiances. The electorate and voting dynamics have changed radically in reaction to Trump’s election, but our analysis has not changed at all.

So, here’s the real curtain raiser for 2024. Those who voted in 2016 continue to only barely favor Democrats, while those in Blue and Purple states who did not vote in 2016 reject MAGA by a substantial margin. As this chart makes clear, Blue and Red states remained solidly Democratic and Republican, respectively, because both those who voted in 2016 and those who have voted since lean Democratic and Republican, respectively. In Blue states, higher turnout will just increase Democrats’ margin. In Red states, higher turnout will just mean that Republicans win by less.8 But you can also see that in Purple states, 2016 voters lean Republican and new voters are solidly Democratic, which means the Electoral College will be decided by how many “new voters" cast ballots next November.

For more on this dynamic, see my recent op-ed in the Washington Monthly on The Emergence of the Anti-MAGA Coalition, as well as my longer Substack post on the same subject.

Footnotes:

Pew estimated that those who voted in the last three elections (the largest block they isolated) favored the Republican House candidates by 1 point—which matches the Catalist voter file. Pew's most important findings were that (1) “Republican gains in 2022 midterms were driven mostly by turnout advantage,” and (necessarily related) (2) the “large majority of voters stuck with 2020, 2018 party preference in their 2022 vote choices.”

I group voting for third parties and skipping the ballot line with not casting any ballot at all for stylistic ease, as there is no practical difference between the first two and the third.

The 15 states were those rated toss-up or lean Democrat or Republican by the Cook Political Report with Amy Walter. Both Catalist and I verified that there was no similar correlation between competitive statewide elections and House results running against the prevailing midterm trends.

Remember that Democrats’ turnout rates compared to 2020 could be a bit lower than Republicans’ turnout rates, since there were more Democratic voters in 2020.

That historical comparison does not include 19th Century elections before women had the vote.

In terms of seats gained.

And, of course, the United States only became a full democracy in 1965.

If this is confusing to you because the new voters are Republican as well, consider this simple example. Let’s say there are 100 2016 voters who are R+10, and 100 new voters who are R+5. Republicans still win the state but by only 7.5 points.

Math is hard. Tuesday here in Ohio we shall learn how many people think 2/3 is greater than 1.