A Cure for Turnout Terror

Part I: What’s up with the anti-MAGA Majority?

Today I want to address the spreading conviction that defeating Trump in November now depends on the voters who put Biden in the White House – voters of color and young people – staying home! (What I call “turnout terror.”) Since I haven’t posted on the election in a bit, this post will tackle the role “turnout” plays in elections, something that receives little attention and is mostly misunderstood when it is raised.

Victims of turnout terror take “turnout” to be exogenous – something that “happens” in elections like the tides – when it is actually contingent on many factors including the stakes, the candidates and the media. In particular, the data show that the more convinced people are of the dangers of the MAGA agenda the more likely they are to vote.

The post is longish. First, I’ll go through how to look at 2024 through the prism of the vote history of those eligible to vote in November. Then, I’ll suggest how to look at 2024 through the prism of the last four elections, showing how the anti-MAGA majority has shown up, what has motivated them to show up, and how high turnout levels have been integral to Democratic wins. After that, there’s a basic primer on how to think about turnout dynamics with definitions of key terms and other context that might help you better understand the concepts in this post. I very much hope you read that too, maybe even first; I’ll be relying on those concepts through Election Day.

But, before all that, a few other recent developments:

FedSoc SCOTUS: Recently I’ve been focused on the threat posed by the Supreme Court and a MAGA win in 2024 (Constitutional Coup, Supreme Gaslighting). This is even more urgent in light of the news of yet another, and even more sinister, Alito flag sighting as well as the disastrous voting rights decision. Remember, it’s not just Alito and Thomas - even the less clumsy Republican-appointed Justices’ first commitment is to the Federalist Society project. Whatever they rule on “immunity,” without their interference, there should already be a verdict in Trump’s J6 trial by now.

Assassination Plots: Perhaps the most disturbing thing last week was the reaction and indifference to Trump’s assertion in fundraising appeals that he “nearly escaped death” when the FBI raided Mar-a- Lago: “They were authorized to shoot me! …Joe Biden was locked & loaded ready to take me out & put my family in danger.”One of Trump’s lawyers amplified this lie on social media, and Representative Paul Gosar took it a step further, posting “Biden ordered the hit on Trump at Mar-A-Lago.” Trump made these claims in legal filings in the Mar-a-Lago case as well. Fox has repeated the fabrication for days without correction. How is a former president and presumptive nominee claiming (without any evidence) that his political opponent, the sitting president, is using the FBI to kill him and his family not front page news? And, as far as I can tell, no one is holding Republican officeholders accountable for these appalling claims. I’m not aware of a single GOP leader being asked whether they think Biden authorized Trump’s assassination – and if they don’t, why they won’t condemn Trump and fellow party-members for telling such an egregious and dangerous lie.

For the last eight years we’ve seen that these kinds of claims have either been projection (blaming Democrats for what Trump has done or is about to do) or establishing a pretext for his own future actions. Once again, we seem to be wishcasting MAGA’s most dangerous threats as merely empty rhetoric for the “base,” thus making it old news and not a serious concern. Along those lines, Ron Brownstein’s new piece, Trump’s Stop-and-Frisk Agenda, is essential reading.

The Cure for Turnout Terror

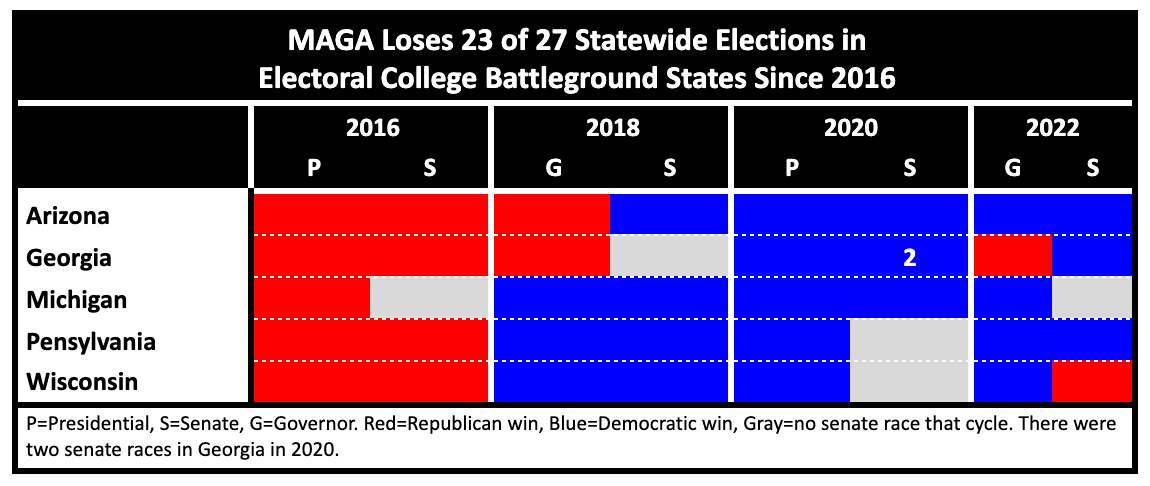

Today, with just 16 weeks before the first ballots in the 2024 elections will be cast,1 I want to revisit my piece about “The Emerging Anti-MAGA Majority,” to see whether that coalition, which has defeated MAGA in 23 of the 27 statewide elections held since 2016 in the five states Biden flipped in 2020, is still poised to defeat MAGA in the Electoral College battleground again in 2024.

At the beginning of 2023, it seemed as though Biden, despite his poor approval ratings, would be heavily favored in a rematch against Trump. After all, he had beaten Trump by 4.5 points in 2020, and since then there has been January 6th, 91 indictments, and the Dobbs decision, as well as Democrats’ unprecedented success in those battleground states for the party in power in a midterm. (See “Red Wave, Blue Undertow.”)

Yet, since last summer, polling consistently shows the race tied or Biden trailing. That’s because Democrats' recent victories have depended on an essentially unprecedented rise in turnout rates and support from young voters and voters of color – groups that polling now consistently shows moving away from Democrats.

That has led to what I’ll call “turnout terror,” the idea that high turnout levels in November will spell doom for Biden. As Nate Cohn correctly notes, “To an extent that hasn’t been true … disengaged voters are driving the overall polling results and the story line about the election.” Over the last few months, we’ve seen many stories along the lines of The less you vote, the more you back Trump, Why Less Engaged Voters Are Biden’s Biggest Problem, The Unusual Dynamic that Could Decide the 2024 Elections and The Next President Might Be Chosen by Indifference.

Before we can address the question of whether Biden needs a “low turnout election,” or assess the danger posed by “disengaged voters [driving] the overall polling results,” we need a better way of thinking about voters in the age of MAGA.

Like what I call “mad poll disease,” turnout terror is caused by not recognizing that the factor most certain to determine the election outcome is one we can’t know ahead of time. That factor is: What will the election seem to be “about” to most voters by October? Will it be a referendum on the Biden administration – or will it be a referendum on whether America should be ruled by MAGA? (For stylistic ease, I’ll refer to the alternatives as either the “MAGA election” or the “Biden election” even though, of course, the reality will be something along a continuum, closer to one or the other.)

If we imagine a single undecided voter picking between Biden and Trump in a voting booth, it might seem painfully obvious why this frame would matter. But it is less obvious that what the election is “about” also affects who turns out to vote.

Since 2016, whenever an election has been “about” MAGA, turnout rates have been much higher than normal, and Democrats have won much more often in those contests. If the Trump and MAGA agenda is salient in October, I am confident turnout will again be at historic highs and that Biden will do as well or better than he did in 2020. But if the economy, immigration, or a similar issue is center stage, turnout levels will be lower, as will Biden's prospects for an Electoral College victory.

That said, even if it's less of a “MAGA Election” than it was in 2020, Biden may be better suited than, for instance, Presidents Carter or George HW Bush were, to pull off a victory on unfavorable terms. That's because he goes into the last five months with a larger base of support among those who are almost certain to vote.

Voter Turnout Rates in the MAGA Era

Voter turnout rates since 2016 have been extremely high, to an extent that is without recent precedent. This graph shows the turnout rates in presidential and midterm elections since 1932.2 The boundary lines for presidential (purple) and midterm elections (orange) are set at +/- 3 percent of the “turnout era” average. Turnout rates have stayed remarkably stable for decades at a time – indeed, the 11 midterms over the forty years between the lowering of the voting age and 2014 were all within three points of the average. But the last three elections have literally been off the charts.

First, note the stability from 1932 through 1968 (36 years), then the drop in 1972 that came when the voting age was lowered. This was followed by another stable period of 30 years until 2004, when Bush became a particularly polarizing figure during the Iraq War. Thus, while the 2004, 2008, 2012, and 2016 presidential elections were hyper-partisan, driving higher turnout rates, the midterms (2006, 2010, and 2014) were not: as you can see, there was no change in turnout rates from previous contests. That all changed with the MAGA era, which has seen midterms look more and more like presidential election years.

Additionally, we have seen an enduring paradox over the last three cycles. On the one hand, there has been an accelerating collapse in public confidence toward America’s basic institutions, as well as its leaders – which in nearly all other times and places dampens voter participation. Yet, at the same time, turnout levels over the last three elections have set records. The reason? Disaffected voters cast ballots when they believe that if the other party wins, they will lose the freedoms they now take for granted – whether it’s the freedom to own an AR-15 or to have access to reproductive health services.

The “Most Likely Voter” Explosion

For the purposes of this post I’m going to divide eligible voters into four categories, based on how many times they have voted in the last three elections: most likely to vote, very likely, somewhat unlikely, and those who haven't voted at all. (Definitions in the chart below.) That is not quite the ideal for categorizing the electorate that I lay out in the Primer at the end of this post, but it’s close enough and matches important contemporary polling data.3

As you can see, “most likely” and “very likely” voters have, together, constituted about 60 percent of all voters in the last two presidential elections.4 As you can also see, there are sharp drop offs in the turnout rates between each category. This makes the categories at the top of the spectrum even more important, and is part of why it is so useful to conceptualize the electorate this way ahead of each election.

Most Likely Voters

Importantly, until now, “most likely” voters have been synonymous with “habitual voters” – those Americans who vote every other November regardless of the stakes. (For more on habitual voters, see Primer below.)

As you can see from the chart below, there was very little change in the number of “most likely” voters going into the 2016 and 2020 elections. But going into this election, there are nearly a third more of the “most likely” voters than there were before the last two elections! That 18 million voter gain reflects the conversion of previously “very likely” voters into “most likely” voters across all demographics.

The right panel above shows that the “most likely” voters today represent a major generational transition from 2016. The Greatest and Silent Generation voters are now 13 points less a share of the most likely voters, and Boomers 4 points less a share of the most likely voters, than they were before the 2016 election. That’s a 17 point share drop for the oldest generations over 8 years. Meanwhile younger voters (Gen Z and Millennials) increased their share by 12 points, and Gen X increased its share by 5 points.

The left panel above shows that the white non-college share of the group declined by 5 points since before 2016, while the share of voters of color went up by four points and white college voters went up by only 1 point. In other words, thinking just in demographic terms, instead of conceptualizing Democrats’ improving fortunes with the most likely voters as due to their gains with white college voters (who make up only one third of the group), understand that about one sixth of the group that was older, disproportionately white non-college voters has been replaced by younger, disproportionately voters of color.

This should provide a necessary corrective to the idea that Democrats are doing better now with the “most likely” voters solely because of how much better they are doing with white college voters now than they were eight years ago. While it is true that Democrats are doing better with white college voters, that’s not the most important reason that Democrats have improved with the “most likely” voters today.

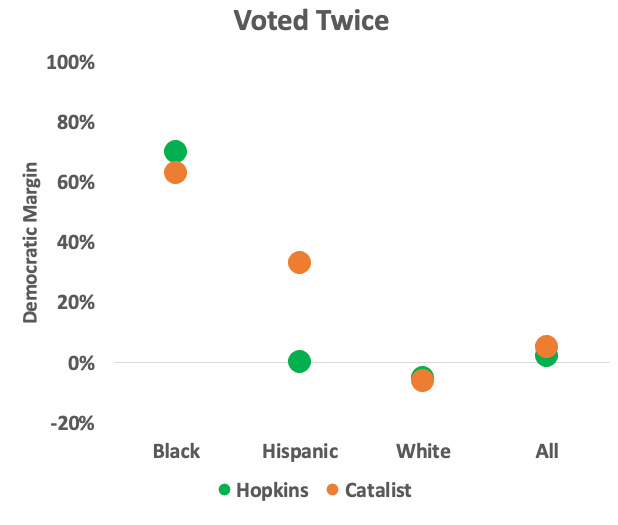

All evidence points to those “most likely” voters being at least as, or more, Democratic-leaning than those with the same vote history ahead of the 2016 and 2020 elections were.5 Now, let’s return to the FiveThirtyEight piece “The less you vote, the more you back Trump,” because it provides current polling by vote history and demographic categories. The following graph plots the Hopkins polling reported in that piece by vote history and race/ethnicity as green bubbles, and Catalist modeling of partisanship for those combinations of vote history and demographic categories as orange bubbles.

The current polling shows Biden doing better than he did previously overall and with white and Black voters who voted in the last three elections, and trailing a hair with Hispanic voters.

“Very Likely” Voters

“Very likely” voters, those who voted in two of the previous three elections (including midterms), were a fifth of voters in the 2016 election and a quarter of 2020, rising from 36 million ahead of 2016 to 45 million ahead of 2020 and 2024. That’s because of the enormous increase in turnout rates for the 2018 midterms which, roughly speaking, converted previously regular voting presidential voters (1 of 3 in this schema) into 2 of 3 voters for the 2020 election. This group, according to Pew and Catalist, was very Democratic in 2020. Looking forward to ‘24, the number of very likely voters has not changed, and according to Hopkins’ polling, this group is essentially as Democratic as Catalist’s modeling found it was for 2020, except for Hispanic voters, to which I’ll return in another post.

But, remember that “very likely” voters heading into 2024 are a group that voted in two of 2018, 2020, and 2022. There are differences between the half who voted in 2020 and in the Blue Wave 2018 midterms and are modeled to be about 10 points Democratic, and the other half, who voted in just 2020 and 2022 and are about half as Democratic. (No Hopkins data was reported for that further breakdown.)

“Somewhat Likely” Voters

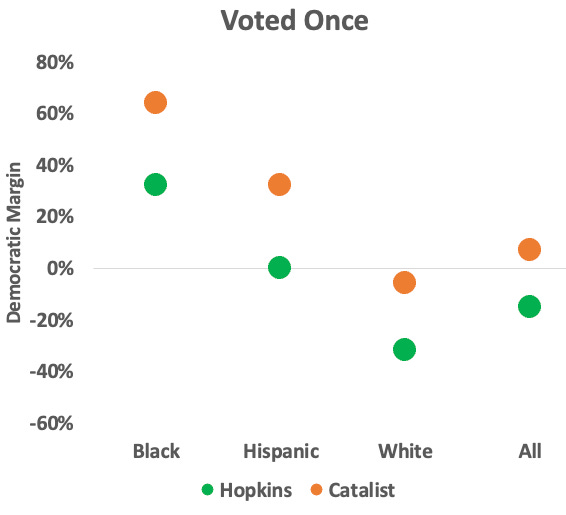

There were about 40 million people who had voted only in one of the last three elections ahead of the 2016 and 2020 elections, and there are 44 million in that category ahead of the 2024 elections. Here we can see dramatically how the preferences of less engaged voters are driving polling now. Overall, and in each demographic category, there is a very wide gap between the reported polling (green bubbles) and Catalist modeling (orange bubbles) for them in 2020.

According to Catalist modeling, there’s not much difference based on which of the three elections qualified voters for this category.

Haven’t Voted

Like somewhat likely voters, those who haven’t voted in any of the last three elections are now polling systematically less Democratic than Catalist’s modeling predicts.

This represents a complete reversal of those voters' preferences in 2016 and 2020. According to Pew’s post-election validated voter studies, Clinton and Biden led Trump by a much greater margin among all those eligible to vote than they did among those who cast ballots (2016, 2020). In the left panel, you see how the number of eligible voters supporting Trump (light red) but who didn’t cast a ballot barely increased from 2016 to 2020, while the number supporting Biden compared to Clinton (light and dark blue), but who didn’t cast a ballot, increased a lot more.

Thus, as you can see in the right panel, in 2020, the turnout rate for Democrats lagged the turnout rate for Trump supporters by even more than it had in 2016. But Democrats still won by turning out a somewhat smaller portion of a much bigger pie. At the same time, Democratic victories remain narrow ones because their turnout rates lag Republican turnout rates. (For more detail see “Most Americans Reject MAGA. Will They Vote?”) (See Primer I below for a fuller explanation of turnout rates.)

As I always do, I present this argument with the caveat that my purpose is not to convince you not to worry. As I wrote in “A Cure for Mad Poll Disease” and “Mad Poll Disease Redux,” polling can’t give us any more confidence in the November outcome than we already have in what we know: that, as it has been since 2016, that result will be determined by very small margins in the six states we already know, and that who prevails is within the margin of our effort.

Revisiting the Anti-MAGA Majority Elections

With hindsight now, and with this understanding of turnout in mind, it’s well worth revisiting the last four cycles to see how consistently the patterns I’ve just described played out. The throughline is this: The MAGA agenda was, and continues to be, enormously unpopular. At the same time, Americans have been broadly unsatisfied with the direction of the country and have lost confidence in institutions and national political leaders, and they hold the party in power responsible. As a result, the mostly diminishing size of MAGA’s electoral defeats reflects the tension between the extent to which voters are tuned in to MAGA threats (less and less since 2018) and the extent to which they see Democrats responsible for the current state of affairs (more and more since 2018).

The 2016 Presidential Election

For good reason, the crumbling of the Blue Wall, and the existence of “Obama-Trump” voters, drew the greatest attention in the 2016 presidential election. But, not surprisingly, as the first presidential election in which both candidates had net negative favorability, fewer people voted for Clinton and Trump combined than had voted for Obama and McCain combined eight years earlier.

The 2018 Midterms: Blue Wave; Red Undertow

The significance of the 2018 Midterms has been overlooked as it appeared to be a typical backlash against the party in power – Trump and the Republican Congress. Interestingly, when people talk about Trump amnesia, they usually refer back to 2020, and themselves misattribute it to voters recalling the time before the pandemic. This needs to be corrected.

Trump was never more unpopular than he was in 2017 and 2018, when with the power of his trifecta, he came close to repealing the Affordable Care Act. ACA repeal was the most unpopular initiative proposed since Bush tried to privatize Social Security. Trump’s net approval was about 2-3 points worse in his first two years than in his second two years. This is a sharp contrast with the first (or only) term of every other president (other than Clinton) beginning with Nixon, who were less popular in their third and fourth years than they were in their first and second years. In other words, a strong case can be made that amnesia for what Trump did when he had a trifecta, given that he is almost certain to have one again if he wins in November, is far more consequential than voter amnesia for how badly Trump bungled the pandemic in 2020.

While the midterm might have looked “normal” with Flatland thinking (see Primer below for more on “Flatland”) – after all, Democrats’ national 7.4 point margin was not much different than their 7.6 point margin in the 2006 Blue Wave in the second George W. Bush term – how it happened was much different. As you can see in this next graph, the increase in the turnout rate was truly unprecedented, whereas the increase in turnout behind the 2006 Blue Wave was trivial.

Importantly, the Catalist and Pew analyses of the midterms agreed that the number and Democratic margin of those who had not voted in 2016 was extraordinary, and many who had voted for Republican representatives in 2016 voted for Democratic ones in 2018.

But the 2018 midterms, unlike all wave elections before it, had an opposite undertow as well. In 2018, incumbent Democratic Senators Nelson (FL), Donnelly (IN), McCaskill (MO), and Heitkamp (ND) were all defeated. Going back to at least 1980, it is unprecedented for the President’s party to have so many of its incumbents unseated while still improving their overall majority. Moreover, two of the three who held on in Red states barely improved on their 2012 margins (Tester and Brown), and Manchin barely won after having been elected in a landslide four years earlier.

The 2020 Presidential Election

In 2020, Biden won the people who had voted in 2016 by the same insufficient margin Clinton had (about 2 points) – but he flipped five states because of the unprecedented-in-recent-times increase in the turnout rate I’ve already discussed.

The following chart, based on the VoteCast Exit polling, captures what I developed at much greater length in “The Emerging Anti-MAGA Majority” (and corroborated using Catalist voter file data as well as other polling): those who did not vote in 2016 but voted in 2020 and reversed the result in the five states that flipped. In these states, habitual voters skewed a bit Republican, while the potential voters who turned out skewed VERY Democratic.

Start with the hollow bubbles, which represent the actual 2016 results in the five states. Next, the solid red bubbles represent VoteCast’s 2020 results for those who said they voted in 2016. As you can see there is no, or almost no, difference between how they voted in 2016 and 2020. The blue bubbles represent VoteCast’s results for those who hadn’t voted in 2016. Those voters chose Biden by margins of 8 to 16 points! It was those large margins that pulled Biden across the line in those states. In other words, Donald Trump would have won the Electoral College vote had Biden relied merely on those who voted in 2016 changing their minds.

Here’s another way to look at it. In 2020, the turnout rate was 66 percent, about 7 points higher than it was in 2016. As a result, Biden’s two party share rose to 4.5 points from Clinton’s 2.1 points - an increase of about 2.4 points. In the next table you can see how turnout rate and Democratic support trends moved together. In Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, the turnout rate and Biden’s support increased by about the same as they did nationally. But in Arizona and Georgia, where Biden’s support grew the most, turnout rates increased substantially more.

The reverse has also been true. If you subscribed to Weekend Reading in 2020, you know that I was warning that it was very likely that polling was overestimating Biden’s support in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin based on the relative lack of enthusiasm of Democratic base groups relative to Republican base groups (based on their relative registrations beginning in June and then in early voting across the country, but especially in those three states). Thus, Biden fell about 3.5 points short of 538’s final projection, but especially so in those three states: Michigan by 6 points, Pennsylvania by 4 points, and Wisconsin by 8 points.

The 2022 Midterms: Red Wave; Blue Undertow

In 2022, MAGA came up empty in the Electoral College Battleground states, but rode a Red Wave in the rest of the country, and so flipped control of the House of Representatives. Again, turnout rates were key, equalling their historic 2018 highs in the battleground states while dropping down elsewhere. The following table compares the number of voters in the all-time high in 2018 to the number voting in 2022. While 6 percent fewer people cast ballots in 2022 than in 2018, 4 percent more did in the six Electoral College battleground states. Meanwhile, in the three states I call Blue State Blues, fully 11 percent fewer ballots were cast in California, New Jersey and New York, costing Democrats six seats and control of the House of Representatives.

In states where MAGA was competitive in 2022, Democrats now have four more seats in the House and four more in the Senate than they did in 2018 with their Blue Wave gains. Yet they have 25 fewer seats in the other states. In the MAGA Statewide Competitive states, turnout was exactly the same as it was when turnout records were broken in 2018. In the other states, turnout rates dropped 5 points.

Conclusion

In our current political era, knowing and believing what Trump and MAGA plans to do makes people more likely to vote.

The dramatic change in partisan preferences for somewhat likely voters and those who haven’t voted is the crux of the uncertainty about the outcome of the 2024 election. But it would be a mistake to think that the portion of these less likely voters was dependent only on how large the turnout ladle that scoops them up in November will be. Rather, turnout rates will depend on what motivates those less likely voters to vote, given they have been all but sitting out the last three elections. In our current political era, knowing and believing what Trump and MAGA plans to do makes people more likely to vote: for better or worse.

For the most part, contingent and new voters (see primer) are dissatisfied with America’s direction and have vanishingly little confidence in the nation’s institutions. Very disproportionately young, they came of age after the Great Recession into an incredibly dismal economy, with foreshortened prospects. They were the most dislocated by the lockdown, either losing jobs that were already disappointing or forced into juggling multiple gig jobs. They have no reason to believe that politicians can improve their lot, although most are convinced that politicians can make things worse and cannot be trusted. They are the “double haters” that we often hear about – the people who dislike both parties and/or both candidates.

Recent history suggests that contingent voters can and will become more engaged in the coming months. But it’s far from assured that they will become engaged enough to understand why they personally need to come out and vote. This is not a reason to panic and make predictions of doom; it’s a reason to get to work at keeping those predictions from becoming self-fulfilling prophecies. This isn’t just a job for political campaigns; it’s the job of all of civil society, including the media, who care about American democracy.

Primer: WTF Is “Turnout” (and Why Am I Only Hearing About it Now)?

In this primer, I’ll begin by providing a necessary vocabulary for using the word “turnout.” Then I’ll provide a more rigorous elaboration on the important distinctions between voters based on their vote history. Then I will put that together to show how without those tools we are forced into thinking about elections in a two-dimensional Flatland. I’ll wrap up by offering some reasons neither popular political discourse nor even mainstream political science pays sufficient attention to turnout dynamics.

Defining Terms: Rates and Levels

In popular discourse, the word “turnout” can refer to either the raw number of people voting, or to the percentage of people who voted out of all those eligible to vote, or, more occasionally, the percentage a given group constitutes of all those voting. This generates much confusion; for instance, if we never hear about how many total eligible voters there are in pundits’ favorite categories (like non-college voters or Latino voters), we will be in the dark about what it means if those categories’ turnout rates or partisan preferences change.6 In this piece, I will refer to raw turnout numbers as “turnout levels,” and percentages as “turnout rates” (and I encourage anyone who writes about turnout to do the same). Turnout levels equal turnout rates times the eligible population or subpopulation.

Here’s a very simple illustration: Let’s say there are 200 baseball fans, 100 who root for the Yankees and 100 who root for the Red Sox. (Full disclosure: I grew up in Boston.) If we asked these fans to vote on which was their favorite team, but only 51 Yankee fans and 50 Red Sox fans voted (turnout levels), the Yankees would win because of the 1 percentage point difference in turnout rates for Yankee (51 percent) and Red Sox fans (50 percent).7

Now, let’s say that there are still 200 fans, but 110 are Red Sox fans and 90 are Yankee fans. This time around, the turnout rate for Yankee fans is 58 percent and the turnout rate for Red Sox fans is 49 percent. This time the Red Sox will win because they have a higher turnout level even though Yankee fans have a higher turnout rate. The Red Sox will get 54 votes (110 x 49%) to the Yankees’ 53 votes (90 x 58%). This example illustrates why these definitions are so important. In this instance, Red Sox turnout levels went up, but Red Sox turnout rates went down.

Now, notice what I didn’t do. I didn’t begin by taking for granted that the only way to understand the “favorite team” election was by telling you how many of the 200 fans were white non-college, white college, Black, Latino, etc., along with the Yankee/Red Sox split for each of those groups. That makes sense because the “election” is about which team fans favor – not what demographic groups the fans belong to. Especially in an era of highly calcified elections, the same is true for real elections – they are about two very different visions of America, not about the demographic characteristics of voters.

Defining Terms: Habitual, Contingent and New Voters

We need to begin by understanding that voting is an action, not an opinion. Therefore, we must sort eligible voters not by their responses to opinion surveys, but by their actual voting behavior, if we are to incorporate “turnout” into our analysis.

There are three types of voters – habitual, contingent, and new:

Habitual voters, who vote regularly regardless of what’s on the ballot, have a turnout rate of 95 percent, and typically account for about one third of presidential voters, and lean Republican nationally and in the battleground states. This group is disproportionately white and college educated, for two reasons. First, older voters are more likely to vote, so this group reflects the demography of America a decade or more ago. Second, those with more economic stability are more likely to vote, which is reflected in higher turnout rates for college educated voters in each race/ethnic group.

Contingent and new voters’8 participation depends on several interrelated and often mutually reinforcing factors, most importantly:

The stakes, especially if they are convinced they have something to lose (loss aversion).

Social proof, which is whether they believe that people that like them are voting.

Buzz - Taylor Swift, not a spike in interest in the fortunes of the San Francisco and Kansas CIty football teams, explains why the last Super Bowl was the most watched ever.

GOTV (Get out the Vote) efforts - by the campaigns and their allied organizations.

The next graph shows the turnout rates for each race/ethnic group in 2016 and 2020, contingent on how many times they voted in the last three elections. As you can see, voters in every race/ethnic group who have voted in the previous three elections were equally likely to vote in the next presidential election, and nearly so if they had voted in 2 of the previous three elections. However, we see significant gaps among those who had voted once or not at all before each presidential election. For example, in 2020, the turnout rate for Blacks who had voted only once in the previous three elections (the gray bubble) was the lowest (60 percent), and white college (the orange bubble) was the highest (73 percent).

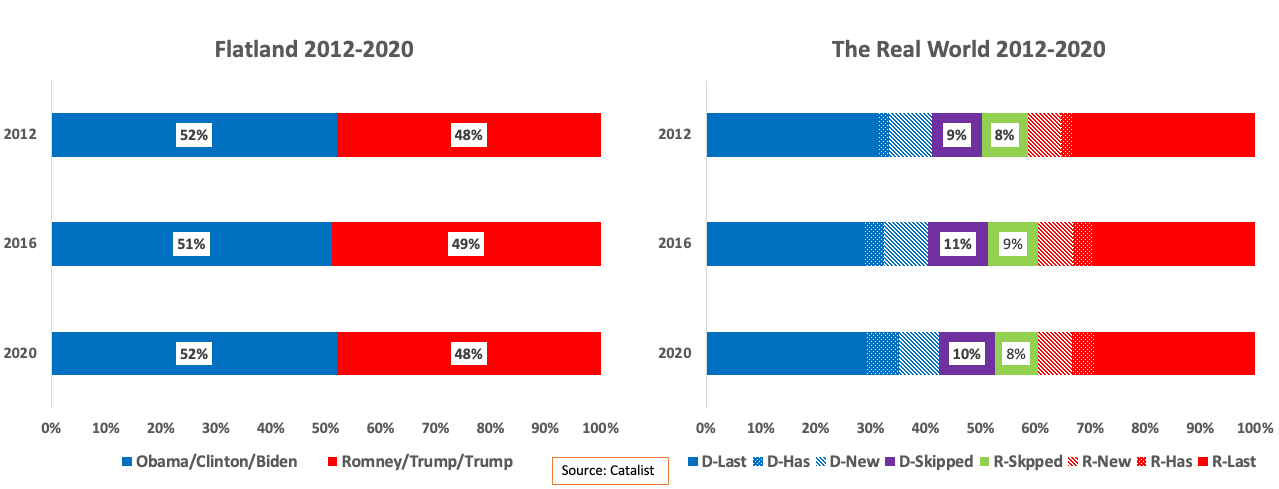

Leaving Flatland

We conceptualize elections as if every American will choose between Candidate D and Candidate R, and that the outcome will be determined simply by voters making a comparison between the two. That presumption is baked into obsessing over polling questions like “who is better on the economy.” That assumption waves away the reality that Americans have a third choice, which is whether to vote at all. Accordingly, I call contemporary political discourse “Flatland” thinking – it’s entirely two dimensional.

The left panel is the way we’ve been conditioned to think about elections. Because there are only two conceptual options, we can’t help but think about Democratic gains as having to come from those who previously voted for Republicans. To the extent we’ve thought about it at all, we either presume that each cycle’s voters are essentially those who voted in the previous election, and that those who didn’t vote in the last election are very unlikely to do so in this one, or that the preferences of those who don’t vote are not sufficiently different from those who do to make a difference. But, as Cohn wrote, “There’s a lot more churn in the electorate than most people realize. Even if the turnout stays the same, millions of prior voters will stay home and be replaced by millions who stayed home last time.”

Now let’s look at the breakdown in the right panel, moving from the edges in.9

Previous presidential election. Over the three cycles, those who voted in the previous presidential election constituted between 59 and 65 percent of those voting (Solid blue and red).

Has voted but not in the last presidential election. They constitute between 4 and 10 percent of those who have voted.

New Voters have consistently constituted 14 percent of the electorate.

Put just those six segments together and you are back in Flatland, the left panel. When we leave Flatland, we can see the voters who have voted before, but sat out that presidential election – the purple and green segments. In other words, Flatland misses 20 percent of the picture. And, as you can see, in each cycle, a greater number of previously voting Democrats than Republicans have been skipping presidential elections. Or, put differently, in each of the three cycles, a greater percentage of previously voting Republicans voted again than was the case for Democrats, costing Democrats 2 to 3 points nationally. That explains much of the paradox I described above – until now, there have been far more Americans opposing Trump than supporting him, but a smaller percentage of them voted.

Why am I only hearing about turnout now?

For many decades when the fundamentals of survey based political science were being developed, Flatland thinking was of little consequence. Between the 1930’s and the early 21st Century, the partisan preferences of those who voted and those who didn’t were not substantially different enough to be of consequence in a period in which nearly every presidential election, as well as who controlled the House and the Senate, were routinely decided by quite substantial margins. But now we’ve seen the Electoral College, as well as control of the House and Senate, determined by elections decided by less than 1 percent in states and congressional districts in which the partisan preferences of those who didn’t vote were the opposite of those who did.

But ignoring turnout levels and rates altogether now obscures one of the most important factors determining the direction of the country. There are basically three reasons that, with the exception of recent New York Times reporting and Pew post election surveys, after each election there is almost no discussion of “turnout” as a factor in elections.

Understanding turnout dynamics is difficult and expensive.

Behavior is much trickier to track and write about than opinions. Polling, at its best, can only measure opinions. Thus, generating what seem like plausible inferences about partisan choice is fairly inexpensive. Methods to anticipate behavior are more expensive and don’t lend themselves easily to quick takes. And worst of all, the most important factors influencing the behavior of those who don’t vote habitually are not manifest until closer to the election.

All of that helps explain why it’s much more difficult to write stories about expected turnout than it is to write stories about the head to head in the latest survey.

“Turnout” and “persuasion” have become euphemisms in ideological debates masquerading as strategic debates about what Democrats should do.

Especially since 2016, when Clinton’s loss was blamed on her reliance on identity politics, “turnout” has become code for those who want Democrats to embrace bold left ideas to rally disaffected voters, and “persuasion” has become code for those who want Democrats to move to the center. Analysts committed to this centrist approach have worked extensively to dismiss as unserious the idea that Democrats would win more elections with greater turnout. Moreover, the deeply flawed idea of the “median voter,” which centrists routinely use as a cudgel against progressives, crumbles once it’s obvious that mobilizing contingent voters who already support you is as or more likely to succeed than convincing people who have already voted for Trump/MAGA to change their minds.10

(To be clear, the question of mobilizing those who have already voted for you is separate from the question of what can be done to bring them back to the polls.)

Unfortunately, that ideological baggage can make it difficult to use the word “turnout” as a straightforward technical descriptor. And, as you saw earlier, Biden’s victory in 2020 depended on the large gains he made with voters who had not cast ballots in 2016.

Wishcasting civic virtue and democratic myths.

As a country that prides itself on being the “oldest democracy,” it’s uncomfortable to acknowledge that turnout rates in the United States are subpar in any international comparison.11 Moreover, we don’t want to acknowledge that we would be a different country if everyone voted. Until 1965, the best we might honestly claim is that our elections established the consent of white Americans. There is obviously a lot more to say along these lines, but in this way, as well as many others, elections are reported on and studied in frameworks that presume that democracy works the way our myths tell us it should.

With the exception of the World War II elections which when military deployment necessarily reduced the turnout rates.

With the exception of the World War II elections which when military deployment necessarily reduced the turnout rates.

Pollsters frequently report their results for registered voters and for so called “likely voters.” There is nothing approaching a common definition of what makes someone a “likely voter.” Likely voter results are simply the pollster’s opinion as to how likely each respondent in the sample is to vote, which should not be confused with my definition in this post, which is strictly on the basis of vote history (the voter file).

Comparable data is not available for earlier presidential cycles as the first canonical file is for the 2008 cycle.

A combination of Catalist modeling, survey results reported in FiveThirtyEight and the New York Times.

This is why, as longtime readers know, I offered a new metric, Contribution to Democratic Margin, as a simple and clean way to express the impact of any group (demographic or otherwise) on Democrats’ electoral success or failure. Contribution to Democratic Margin, or CDM, is simply the partisan preference of a group multiplied by that group’s share of the electorate. This calculation can tell us how much that group contributed to Democrats’ margin in the election. For more on CDM as it applied to various demographic groups in the 2022 midterms, see “Terrible Food, and Such Small Portions.”

Actually, a rounded 0.9 point difference for math nerds who noticed the denominator is now 101.

New voters are those who have not voted before. This group has three components: (1) those who become eligible to vote for the first time, (2) those who have been eligible but have never voted and (3) those who are voting in that state for the first time, but may have voted in another state earlier. Together, this is a small group, rarely constituting as much as 10 percent of total turnout, and generally impacts the overall vote by only about half a percentage point. Furthermore, shortcomings in administrative and census surveys make observations about those voters less reliable than what I have defined as habitual or contingent voters.

I’ve excluded from the graph eligible voters who have never cast a ballot – which pains me, but should pre-empt arguments about whether non-voters can be motivated to vote.

This article exposes the flaw in the notion that a “moderate middle” bloc of voters are key to deciding elections, something that pundits often use flawed applications of the Median Voter Theorem to argue.

And, of course, the United States only became a full democracy in 1965.

Brilliant as always. Thanks.

Yup, there hasn't been a democratic leader since FDR, that is, one that was elected. Let's always remember BERNIE SANDERS in 2016, the leader for revolutionary change that people were, and still are, looking for. There has never been such enthusiasm for a candidate in my lifetime, and it never has been so easy to organize as for Bernie Sanders. Never seen anything like it. It is no mystery why today so many are so tired of it all, so not energized. Why should they be? When all they get is a contrast in agendas, albeit an agenda of the freaks and a reform agenda - but no revolutionary change. People know that reforms will never provide the fundamental change for the solutions we need. Just more of the same..... If only in 2016.... and again in 2020.