Mad Poll Disease Redux, Harris-Walz Edition

Also: Why Trump really chose JD Vance

When Weekend Reading launched before the Substack era, I was fairly diligent in getting it out every week (thus the title). Over the last two years, I’ve mostly used Substack to publish thorough, single-topic pieces. Now, with less than 90 days to go until the election, I’m going to do my best to get at least one edition out a week with shorter pieces aimed at what’s happening now. I will also continue to publish longer pieces on topics critical to our present and our future.

In today’s edition:

How Harris-Walz Changes the Race

The Harris Bump: A Teachable Moment for Ignoring the Horse Race? Nah.

Forecasting Forecast: Continued Fog

Why Trump Picked JD Vance

How Harris-Walz Changes the Race

In my last Weekend Reading piece, “Election 2024: The Path Forward,” I explained that America’s anti-MAGA majority is still as large as it has ever been:

So far, support for Trump in 2024 is nearly identical to what it was at this time four years ago. The big change is how much less support Biden had this month than he did in July 2020 – nearly 10 points less. We see that difference reflected in the purple lines, which show the doubling of the number of “neither Biden nor Trump” voters who tell pollsters they are either undecided or would choose a third-party candidate. In other words, Trump has not grown his support, but Biden has lost much of his.

Here’s an updated version of my graph from that piece that illustrates this – now incorporating FiveThirtyEight’s new presidential horse race average that pits Harris against Trump. Again, the solid lines represent the 2020 race; the dashes represent the 2024 race; blue and red represent Biden/Harris and Trump; and purple represents those who say they would vote for neither major candidate.

Look at the change from July to August: the extent of Harris’s support increases at the same rate as the extent of opposition to both candidates decreases. Trump’s support, once again, stays the same.

I have long argued that the outcome in this election will turn on whether voters see it as being either “about” a MAGA future, or “about” other issues like Biden’s age and a general dissatisfaction with the status quo. Having Harris as the nominee makes that job much easier, but it’s still not a guarantee.

And, so I repeat my original advice – that we don’t need to pay attention to horse race polls, because we already know everything we need to know about the task ahead:

… when a race is deemed to be within the margin of error, that really means it is within the margin of effort – the work we must always put in to get enough of those who dread a MAGA future to turn out to vote. The only FDA-approved cure for Mad Poll Disease is to pay attention to what matters: the ongoing MAGA threat.

Again, to be clear, I am NOT saying that Harris has the election in the bag. I am only saying that in order to properly understand election dynamics, we have to know better than to take responses to hypothetical questions too literally, give the evidence of the last four elections at least equal weight to the latest survey, and do more to interrogate our own susceptibility to confirmation bias.

The Harris Bump: A Teachable Moment for Ignoring the Horse Race? Nah.

For more than a year, I’ve argued that the political commentary industry has succumbed to Mad Poll Disease, which, briefly, involves drawing broad conclusions from every horse race poll despite the absence of any evidence outside the four corners of surveys to provide external validity to those conclusions.

Perhaps you’ve heard that America is undergoing an epochal political realignment in which Republicans are becoming the party of a multiracial working class coalition. Biden’s poor poll numbers, especially with voters of color and young voters, have been key to this argument. Commentators have been tripping over each other for the last year to claim bragging rights for announcing a realignment that appeared only in polling and never at the ballot box.

Does the chart on the left look as convincing as it did a few months ago? Remember, the arrows only reflected poll numbers at the time, while the rest of the chart reflected actual election results (the version on the right).

Now that Harris is gaining popularity with many of these same voters, it would be nice to see some kind of reckoning from those who overinterpreted Biden’s unpopularity as something more systemic and the dawn of a new political age. We probably won’t.

Again, as I explained in my last post, Trump was not, in fact, “pulling away from Biden,” as many had framed it. Nor were Democratic Senate candidates outperforming Biden because they were “more moderate” than he is. Rather, about a fifth of those who had voted for Biden 2020 were reluctant to say they would do so again.

Now think about how much time you’ve spent getting sucked into the horse race game, and how many resources the media has expended covering the odds instead of the stakes.

Polls can’t measure hypotheticals

Patrick Ruffini, a major proponent of the “realignment” theory, just published a Substack post with this headline: “Polls can't measure hypotheticals: From Biden's withdrawal to Trump's legal woes, the polls this year have been really bad at predicting how voters will react to big events.”

Well, duh.

As I wrote in the original “A Cure for Mad Poll Disease,” less-frequent voters “are notoriously poor at forecasting their own behavior even a month before the election.” And the media, with its overreliance on issue rankings in surveys, is even worse at it, as the fallout from Dobbs showed us:

The combined impact of the J6 hearings and then Dobbs was not fully accepted by the media until after the Kansas initiative made it impossible to sustain the “abortion doesn’t matter" midterm narrative. (Remember – between the Dobbs leak and Kansas, the media was telling us that their polling showed Dobbs wouldn’t matter because, as with J6, few voters were changing their minds about Roe. But it turned out that a hell of a lot of voters were changing their minds about how important Roe was.)

The real question should be why anyone used horse race polls to seriously argue that Trump and MAGA fascism were growing in popularity with young people and people of color. Consider the combination of these facts, which we knew before Biden dropped out:

only 4-5 percent of those who voted for Biden in 2020 said they were now supporting Trump;

those who had supported Biden in 2020, but were now either supporting a third party candidate or were undecided, were strongly opposed to the major elements of the Trump/MAGA agenda; and

those former Biden voters who were undecided or supporting third party candidates were very much not paying attention to the race.

All of this evinced a general grumpiness about Biden’s age and the direction of the country, not some grand realignment wherein “non-white working class voters” were getting turned off by Democrats’ positions on whatever issues a particular commentator wanted to knock the Democrats for.

Even if polls are accurate, they are not predictive

I hope that I can use this moment to convey a nuanced but important point about the “accuracy” of polling. At their best, polls can only be accurate about telling us who people say they will vote for. Good polls can’t reliably predict a Harris win today any more than they reliably predicted a Trump win three weeks ago.

A survey is 100 percent accurate when its results match the results of asking everyone in the population. Thus, if you surveyed 1,000 people and found that 10 percent of them said they were going to quit smoking in a year, it would be considered accurate if 10 percent of all Americans said they were going to quit smoking in a year.

The best polling can do is to be accurate about what people will say when asked on polls. But we should be skeptical that that tells us the whole story, because, of course, fewer than 10 percent will have quit smoking in a year.

In other words, my point, which this moment should make clear, is that being accurate about who people say they will vote for in November is different from being accurate about who they will vote for in November.

Finally, consider how pollsters tell us how accurate they were after Election Day. For the 2022 midterms, FiveThirtyEight said the polling was more accurate than ever since polls were off on the national House vote by only about 2 points! But, consider this. In 2014, Democrats lost the House vote by 5 points. So, if you had assumed that Democrats would not win the national House vote, then a safe range of options would have been from 0 to 5 points. So if you had just split the difference of that range (2.5 points), you would have been less than one point off the actual margin – in other words, about 2 points. Random guessing would have literally been just as good.

Forecasting Forecast: Continued Fog

You can be forgiven if you believe that election “forecasting” is about predicting the future; it’s not. Forecasting is about “predicting” the past.

The statement, for example, that “Trump has a 66 percent likelihood of winning,” does not mean the same thing as, if I roll two dice, I have a 66 percent chance of rolling a 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 or 9. Rather, it means that based on a set of data points selected by the modelmaker (for example, inflation rates and horse race polling), and a set of statistical relationships between those selected data points and election results in the past, the modelmaker is actually saying that if we had seen the same combination of the selected data points in the past, Trump would have won two-thirds of those times.

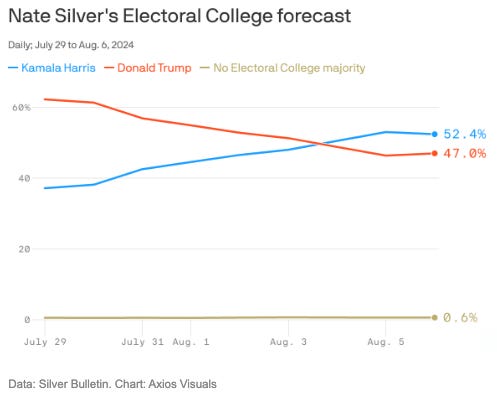

Let’s spend a second with the dice to underscore the difference between scientific probability and election forecasting that is dressed up to be scientific. First, no matter who does the estimating, a Democrat or a Republican, the chance of rolling snake eyes will always be 1/36th. That is obviously not the case for election forecasting. The ongoing “modeling wars” between FiveThirtyEight and Nate Silver should be proof enough of the difference between the common sense understanding of “chance” and what election forecasters are doing. But, apparently not. (TL;DR – FiveThirtyEight’s model had been showing Biden’s chances to be 50-50 +/-, while Silver’s was something more like favoring Trump by 2:1.)

Now, there’s a middle ground kind of phenomenon between dice rolling (where the probability is physically determined and the odds are clearly knowable and indisputable) and elections (where neither the common sense nor scientific meaning of “odds” apply, even when super sophisticated statistical methods are deployed). That middle ground is complex human activities that are repeated frequently. Think poker – or baseball, where Nate Silver and other forecasters cut their teeth.

In those cases, the forecasting models are also predicting the past. But crucially, that past consists of many orders of magnitude more outcomes than Electoral College results. Consider something like batting. Each season there are nearly 200,000 at bats, or nearly 2 million a decade. On the other hand, there have been no more than 18 presidential elections with what is considered reliable polling.1

Heads I’m smart; tails you’re stupid

Here’s a quirky, but highly accurate, presidential model. If a team from the AFC (American Football Conference) wins the Super Bowl, the challenging party wins 60 percent of the time. Thus, based on the “football predicts politics” model, I can confidently say that Trump will win. If Trump wins, I’ll claim bragging rights. But, if Harris wins, I’ll scold you for thinking that I told you that Trump would win, because, you fool, I said that was almost as likely as Trump winning. There was nothing wrong with my model, just your understanding of what I was telling you.

Consider the change in Silver’s model since Biden dropped out (It went from about 2:1 Trump to even). Either Silver’s earlier model grossly underestimated the prospects of Harris replacing Trump (and what that would mean for the race), or we can see that the fine print in the model includes something like, “assuming that all my assumptions are correct.” What’s the point of even paying attention to forecasting models if their warranty doesn’t include out of sample events?

Or, remember FiveThirtyEight’s 2022 Senate forecast when Silver ran the site.

There are two ways of interpreting the radically changing odds over the course of months. Silver’s explanation would be that the changes reflect the additional information available to the model over time as well as the intrusion of exogenous events. Which is reasonable. If I were to estimate your life expectancy, for example, I’m going to be more accurate if I’m estimating it when you are 70 than when you were born. But – and this is crucial – the proper implication of such a wide swing in the odds is to cast doubt on the reliability of the earlier estimates. Yet these are precisely the estimates forecasters tell us to take seriously now.

Unknown Unknowns

The greatest challenges to forecasting are the “unknown unknowns.” Most models do not incorporate exogenous variables that have been stable, so those models cannot account for what happens when those exogenous variables change. History is full of twists and turns, but political forecasting is biased toward what has happened continuing to happen.

For example, in 1988, George H.W. Bush's victory was the fifth GOP presidential win out of the previous six, with the exception of Carter, a devout Southern Baptist, barely squeaking by even with Watergate wind at his back. In 1989, the GOP won the Cold War when the Berlin Wall fell. In 1990, Operation Desert Storm won the Persian Gulf War decisively with almost no American casualties. A year before the election, H.W.'s net approval was +20. And Democrats had controlled the House for the previous 46 years. Yet since then, Republicans have won the popular vote only once in the eight elections that followed, but controlled the House for 10 of the next 14 Congresses.

Decimal Deception

In his latest Substack post on the Walz choice, Silver provided another perfect example of dressing up pseudoscience as science. Look at the last two column headers in the chart below. First, notice the word choice of “chance.” As I just explained, in this instance, the meaning of “the chance of …” is nothing like the common sense use of the word chance, as in, “the chance of flipping heads is 50 percent.”

First, the idea that there is a knowable probability of winning the Electoral College if Harris wins Pennsylvania is Silver’s invention. What he is actually saying is that inside the model he has created, it’s knowable – but that’s only because every such mathematical simulacrum has a mathematical result. When he says that Harris will win the Electoral College 91.3 percent of the time if she wins Pennsylvania, that’s because in 1,000 of his model simulations, Harris loses the Electoral College 87 times. But, of course, Harris won’t win Pennsylvania 1000 times. The claim is unfalsifiable and utterly meaningless.

Second, notice that in the last two columns, all the estimates have a decimal point. But the hard rule in scientific journals is that the number of decimal places should correspond to the precision of the measuring instrument, in this case Silver’s model. For the reasons I’ve just described, it should be obvious that his model can’t be accurate to the tenth of a percent, and he should obviously know that. But, unconsciously, readers cannot help but take numbers with decimal points more seriously than what we already know – that if Harris wins Pennsylvania, it will be really, really weird if she loses the Electoral College.

Why Trump Picked JD Vance

Trump’s choice of JD Vance as his running mate has been seen as a major blunder. The most common explanations for that choice have been either about voters’ preferences (that Vance would help Trump in the crucial Blue Wall states), or Trump’s preferences (for instance, his confidence that Vance, unlike Pence, will do whatever it takes for him).

The most obvious explanation goes unstated: that the Silicon Valley/Crypto faction that now dominates the MAGA Republican Party wanted him there. Peter Thiel, Elon Musk, and others have gone all in on Trump now, and Vance is their guy in the room if Trump returns to the White House – not to mention, with Trump being 79, well-positioned to be his heir.

According to OpenSecrets:

Vance, who owns up to $250,000 in Bitcoin, is a recent champion of the digital asset industry. During his time in the Senate, Vance has drafted legislation that would rework how the Securities and Exchange Commission and Commodity Futures Trading Commission regulate the crypto community — much to the liking of crypto investors.

Putting Vance on the ticket, above all, is about Trump cementing his relationship to the “plutocrat” half of the plutocrat-theocrat MAGA coalition. (As I’ve written, this coalition seeks to take us back not just to the 1950s, but the 1920s, when both robber barons and white Christian supremacists ran unchecked.) Trump hasn’t exactly been subtle about this goal. He’s said flat-out that he is now more supportive of electric cars because of Musk’s endorsement, while he also told a group of energy executives that for $1 billion he would deliver their agenda.

Trump locked down the “theocrat” vote by choosing Pence in his first run, and most of all by appointing Supreme Court justices who would overturn Roe. Still, the bulk of mainstream “corporate America,” even as it has bridled against many of the Biden Administration’s policies, is not firmly behind Trump – and he clearly knows it.

This graph shows the capitalist fracture over Trump, illustrated by the number of Fortune 100 CEOs who have donated to the Republican presidential nominee over the last 20 years. In 2004, nearly half did; 20 years later, none have.2 (Keep in mind that MAGA billionaires don’t show up in this chart because they are not CEOs of major corporations.)

This emerging split, and the sides being taken, shouldn’t surprise us. As Adam Tooze wrote in his indispensable Substack:

At a deep level, crypto ideology shares some elements with the current Republican mood. It is a cocktail mixed of arcane tech, strange futurism, libertarianism, phobic attitudes towards the state and a dark view of human nature. It does not make for a good mix with American liberalism.

…

Given this stark political alignment, Trump has had no difficulty switching positions and coming out wholeheartedly for the crypto cause.

The RNC platform promises that: “Republicans will end Democrats’ unlawful and un-American crypto crackdown and oppose the creation of a Central Bank Digital Currency. We will defend the right to mine Bitcoin, and ensure every American has the right to self-custody of their digital assets and transact free from government surveillance and control.”

For context, again according to OpenSecrets, $121 million is about as much as all of organized labor has spent in this cycle ($155 million), and more than these entire sectors: agribusiness, transportation, construction and defense.

We can’t fully understand American politics without understanding the role corporations and plutocrats play in politics since Citizens United, which opened the floodgates of billionaire spending. (For more, see my post on “Moore v Harper and the Emerging Divisions in the Revanchist Coalition.”) And it matters which specific corporations and plutocrats are doing what in our politics – especially when some of them are embracing a bizarre new type of high-tech authoritarianism.

Weekend Reading is edited by Emily Crockett, with research assistance by Andrea Evans and Thomas Mande.

I’m using 1952 as the earliest point, the first election after “Dewey Defeats Truman” and the beginning of the American National Election Study series.

This graph was published before reports that Musk would give $45 million a month to his pro-Trump America PAC. He has since backed away from that number, saying that he has given “at a much lower level.” Either way, the point stands.

This is the absolute best thing I have ever read on polling. Superb! I will be recommending it in my newsletter this evening to my subscribers. Keep up the good work!

Michael — great post as ever.

One very minor quibble as the author of the now infamous racial realignment chart:

That chart (which on balance I regret making) didn’t actually appear in my article on the topic (non-paywalled link here https://on.ft.com/4dyARFJ), and wasn’t really part of my argument. The argument in the article *was* based on results at the ballot box, not from polls during the campaign, and the key chart is the second one down (or see here https://x.com/jburnmurdoch/status/1767198845321044213), and the realignment I talked about in the piece (and the Twitter thread) is the increasing tendency of Black voters to vote in line with their stated ideology, which is a pattern that has been unfolding clearly and steadily since 2012.

As I said on the 538 podcast shortly afterwards, that pattern was by no means destined to continue. But it was something that had been playing out over several election cycles, not just a phantom trend only appearing in intra-election polls.