Calling This Court "Supreme" Is Obeying in Advance

When will legal elites stop passing off tyranny in robes as the rule of law?

The Roberts Court heard oral arguments this month in Louisiana v. Callais, which could mean the final blow to the Voting Rights Act – by some estimates eliminating a dozen or more congressional districts that have ensured that minority communities have a voice in Congress. Yet, whether it’s the mainstream media or centrist or progressive publications, the headline about this has been some version of Supreme Court Appears Poised to Weaken Voting Rights Act. (Endnote1)

What’s the problem with that headline? If the Voting Rights Act is undone, it won’t be at the hand of “the Supreme Court,” an independent institution that’s just calling balls and strikes. A more accurate headline would be Republican Justices Appear Poised to Entrench Republican House Control.

As I wrote several months ago in “The Courts Will Not Save Us”:

When we say “the Supreme Court did X,” even if we loudly object to X on the “merits,” we give X unwarranted legitimacy by naming the hijacked institution rather than the hijackers. When progressive institutionalists scold us for undermining the credibility of the Court, they do not realize that attributing its worst opinions to the institution rather than its hijackers degrades public trust in the institution even more.

To be clear, the harms to those whose voices will no longer be represented in their government, and for all of us when their voices are silenced, are much larger than the purely “partisan stakes.” And as I’ve written here, in other contexts naming the Roberts Court as “Republican” is too narrow a frame; they are not merely partisan hacks but agents for those who elevated them to the Court. It’s especially problematic when those who do label the majority as “Republican” justices feel compelled to label the other three “Democratic justices,” because it suggests a symmetry that simply doesn’t exist. (Endnote2)

But when legal and media elites can’t even bring themselves to name those partisan stakes, and when even progressive critics keep referring to the Roberts Court’s legal Calvinball as “Supreme Court” rulings, they are losing the plot and conditioning all of us to accept what we never would otherwise.

Dayenu

The Passover Seder includes singing “Dayenu,” which means “It would have been enough for us.” Here, I wonder why none of the following has “been enough” to deter “objective” news organizations and liberal commentators from continuing to confer institutional legitimacy on the nakedly agenda driven project that is the Roberts Court.

In the spirit of Dayenu …

It should have been enough that Republican Supreme Court majorities have repeatedly intervened to ensure their party’s nominee reaches the White House:

Stopped the counting of ballots in Florida to give the 2000 presidential election to George Bush3;

Delayed ruling on presidential immunity to prevent Trump from standing trial for crimes we all witnessed on TV, and then reversed the unanimous decision of the appeals court to create a previously nonexistent doctrine of broad presidential immunity from prosecution;

Reversed the effect of the insurrection clause of the 14th Amendment—from requiring a two thirds vote by Congress in order to allow an insurrectionist to serve, to requiring prior legislation to prevent an insurrectionist from serving.

It should have been enough that no other Supreme Court majority has included as many party apparatchiks:

Three assisted Bush’s legal team in 2000 (Roberts, Kavanaugh and Barrett4);

Five have served in Republican Administrations (Thomas, Alito, Roberts, Gorsuch and Kavanaugh5);

One cut his teeth in the Ken Starr investigation of Bill Clinton—where colleagues accused him of leaking grand-jury information to the press, an early rehearsal for the partisan lawfare he would later sanctify from the bench. (Kavanaugh6)

It should have been enough that the billionaire-backed Federalist Society7, whose sponsors are the funding and mobilization base of the Republican Party, vetted and financed multi-million dollar confirmation campaigns for the Roberts majority justices.

It should have been enough that George W. Bush was the first president in half a century not to vet his nominees with the non-partisan American Bar Association (ABA), instead vetting them with the “officially” non-partisan but transparently partisan Federalist Society.8

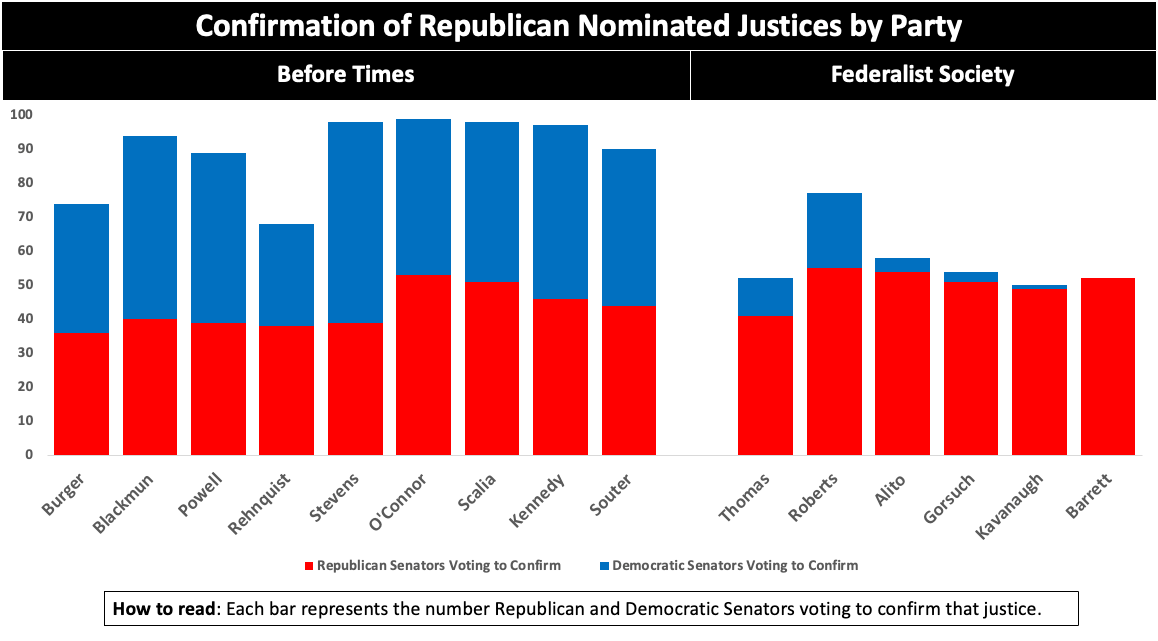

It should have been enough that no other Supreme Court majority has consisted of justices confirmed on such a purely partisan basis.9 The left panel shows the partisan support for the nine justices nominated since the Voting Rights Act by Republican presidents, and the panel on the right the six nominated beginning with Clarence Thomas (the current Republican majority on the Court).

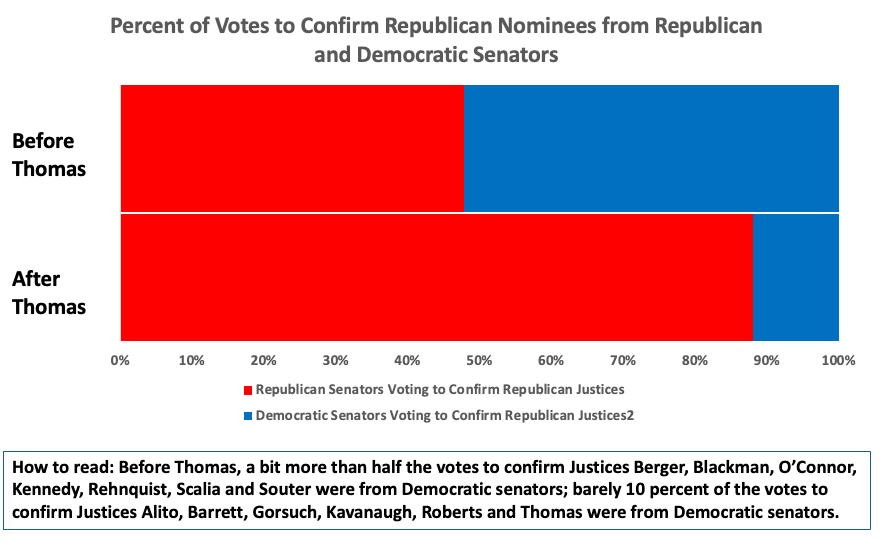

And if that’s not visually arresting enough, this next graph shows this sea change in the aggregate. Of the 807 senators who voted to confirm the pre-Thomas nine, 421 – or more than half – were Democrats. Of the 343 senators who voted to confirm the current six, only 41, or barely 10 percent, were cast by Democratic senators. (Endnote10)

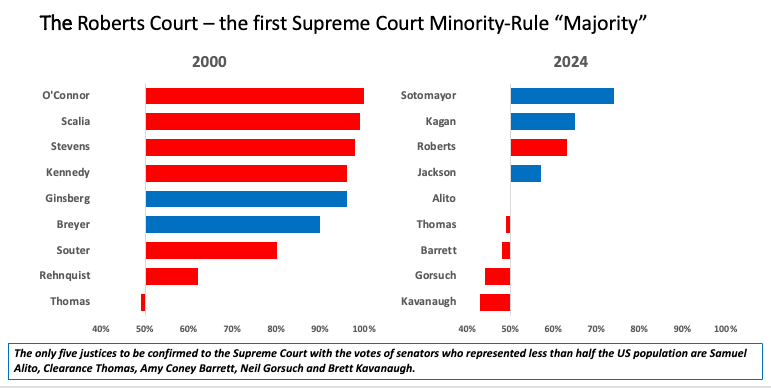

It should have been enough that no other Supreme Court majority in American history has less of a claim to democratic legitimacy11:

Five of the six justices were nominated by presidents who did not win the popular vote;12

Five of the six justices were confirmed when Republicans held the Senate majority despite receiving fewer votes nationwide than Democratic senators had at that time;13

Neil Gorsuch serves because McConnell refused to allow the Senate to consider Merrick Garland, and Barrett serves because McConnell rammed through her confirmation after tens of millions of Americans had voted in an election that Trump would lose;

Five of the six justices were confirmed by senators representing less than half of the US population (this chart compares the Bush v. Gore Court to the present one)

It should have been enough that two of the justices who were sympathetic to Trump’s efforts to reverse the outcome of the 2020 election did not recuse themselves in Trump related cases, nor did Roberts do anything to address that.

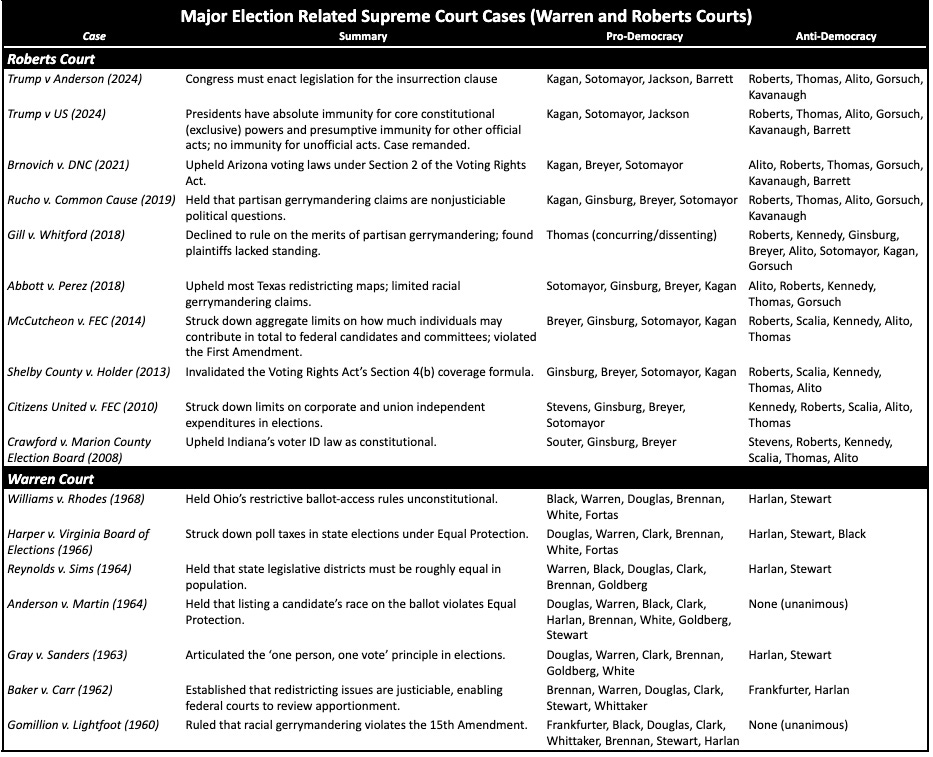

It should have been enough that every Roberts Court case that has assisted Republicans has been decided without a single vote from the justices appointed by Democratic presidents. Both-siders are quick to counter that the Warren Court profoundly changed the way we do elections as well. But, let’s compare those two overhauls. The Warren revolution centered around cases that eliminated the poll tax and mandated “one person, one vote.” The Roberts Court revolution featured cases that allowed unlimited corporate spending, made it more difficult to vote, lifted the limits on how much individuals could give to candidates and parties, and allowed racial discrimination in drawing districts as long as it was on the basis of partisan considerations. In every one of the 10 Roberts Court democracy-shattering cases, not a single justice appointed by a Democratic president went along, and in four, at least one justice appointed by a Republican president did not go along either. On the other hand, every one of the seven democracy-bolstering cases decided by the Warren Court were decided by bipartisan supermajorities.

It should have been enough that this is exactly what the plutocrats said they would do, in the Powell Memo and in the Horowitz memos, not to mention thoroughly credible accounts of the execution of those plans by Jane Mayer (Dark Money), David Daley (Antidemocratic), The Lever (Master Plan), and Lisa Graves (Without Precedent), and periodic exposes of Federalist Society activities by ProPublica and others.

It should have been enough that this is exactly what the religious right said they would do, as well documented early and often by Katherine Stewart (Money, Lies and God), Frederick Lane (The Court and the Cross), Daniel Williams (God’s Own Party) and Joan Biskupic (Nine Black Robes).

It should have been enough that conservative jurists regularly called out the Roberts Court for creating new law, including Michael Luttig and Richard Posner, who blasted the Shelby decision by pointing out that there was “no such principle as … equal sovereignty.”

It should have been enough that fellow Supreme Court justices’ blunt dissents called Roberts out for making things up, including Justices Stevens (“they changed the case to give themselves an opportunity to change the law”(Citizens United), Sotomayor (“Today’s decision … makes a mockery of the principle … that no man is above the law.” (Trump v US), Kagan “(What is tragic here is that the Court has (yet again) rewritten...” (Brnovitch) and many others)

And yet, all of that is still not enough for today’s legal establishment to name the Roberts Court for what it is: judicial tyranny on behalf of organized wealth and a mobilized theocracy.

This failure amounts to …

Obeying in Advance

The law-school deans, the “senior analysts,” the columnists, and the network of former clerks who dominate legal discourse insist that what we are witnessing is a rough patch, not a constitutional collapse. For the last twenty years they have met every Roberts Court usurpation of our freedoms and democratic agency with a jurisprudential critique instead of a call to arms. By doing this, they have been complicit, however unwittingly, in allowing the MAGA regime to rise and thrive.

A key reason they did this was that liberal reverence for the Court curdled into obedience to it.14 A romantic view of the Court, beginning with Brown v. Board of Education, was incomplete and out of date. (Endnote15) In fact, the real breakthroughs of the civil rights era came not from judicial enlightenment but from the disciplined sacrifice of a mass movement that forced the political system to act. It was movement politics, not judicial grace, that produced the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act—the statutes that finally made the Constitution real for tens of millions of Americans.

Yet each time Roberts’s majority chopped away at those gains, from Shelby County to Brnovich, the liberal legal establishment minimized the damage, reassuring us that “the system would hold.” Many ruled out any response that might (in their minds) jeopardize future litigation. Thus, the establishment allowed the political muscle of the civil-rights coalition to atrophy. It left us with no strategy for what to do when the Court simply rules against democracy itself. When Roberts first gutted the Voting Rights Act in Shelby, there was no plan B beyond the courts (specifically, using Section 2 as a workaround). When he gave Trump functional immunity in Trump v. US, there was no plan at all – other than encouraging people to vote. Liberals overvalued litigation and undervalued the necessity of countervailing political power.

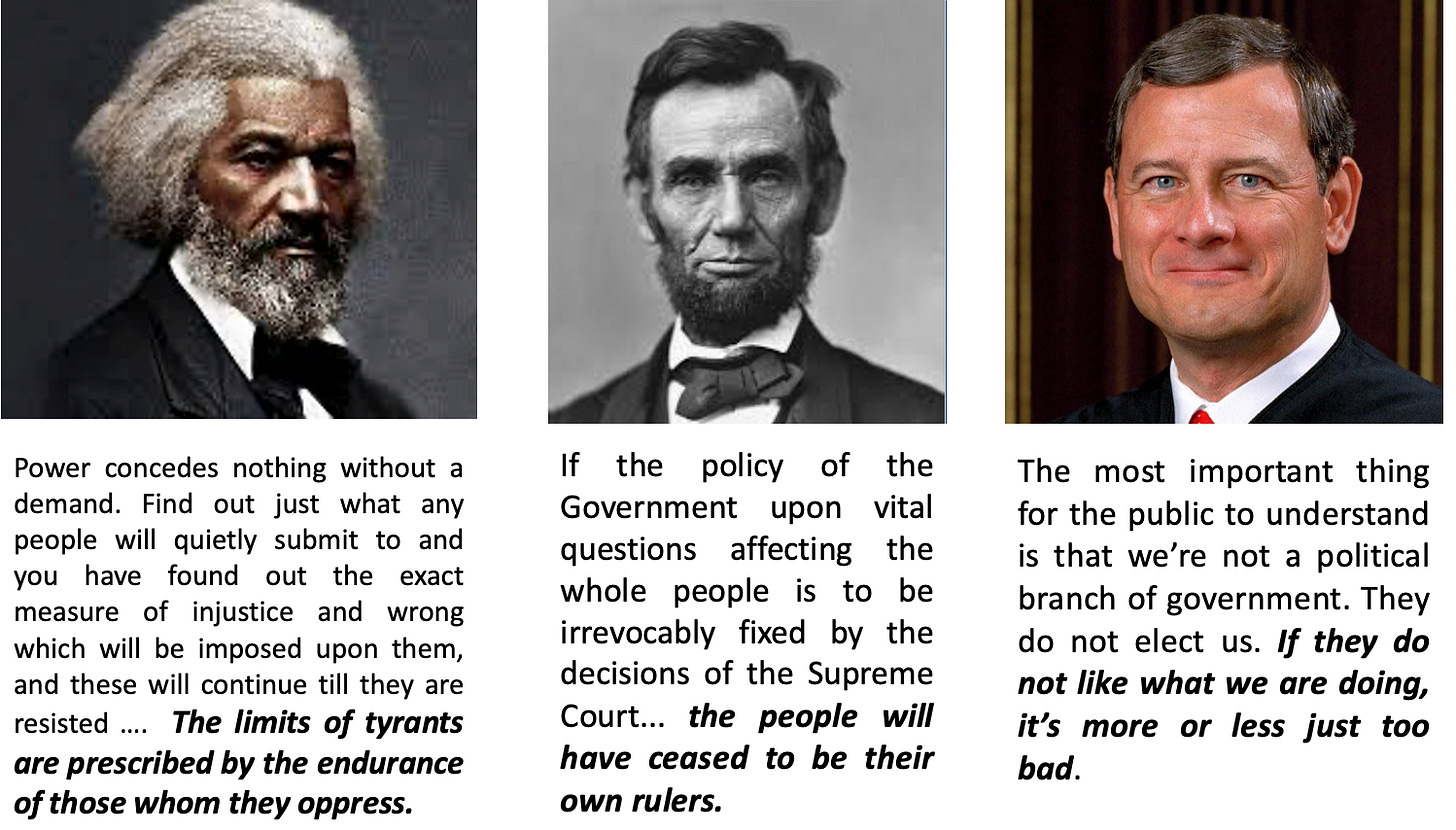

Yes, it is good that people are finally mobilizing against Trump’s open promise of dictatorship. But the unsettling truth is that while so many have rallied to stop a would-be king, no one did, or is, to stop the kingmaker.16 Trump continuously says the quiet part out loud; Roberts said it with a smirk in 2009: “If the public doesn’t like what we’re doing, it’s more or less just too bad.” We rightly fear Trump’s ambition without even realizing that we have been trained to grant Roberts his. That is what “obeying in advance” looks like.

Shadows and Shadowcasters

We have no hope of speaking truth to power, if we can’t bring ourselves to speak truth to each other. If you doubt the stakes of language, try a simple swap: replace “the Supreme Court” with “the Roberts Court” in your favorite explainer or podcast. Watch how the haze of institutional legitimacy subtly lifts.

In another recent essay, Shadows and Shadowcasters, I wrote:

A century ago, John Dewey observed that “politics is the shadow cast on society by big business.” Now, in the 21st century, other organized interests—most consequentially the institutional forces of white Christian nationalism, such as Evangelical churches—cast shadows as well. Yet in today’s liberal America, to be taken seriously and to gain a major platform, one must behave as if the shadow itself is the only reality that matters. The shadow-casters are treated as occasional curiosities, but ultimately as inconsequential—and those who insist on calling too much attention to them are dismissed as alarmist, ideological or marginal.

Especially in the wake of the immunity ruling, the criticism by the legal establishment has become harsher and edgier. Yet much of it still fails to recognize that the “Court” per se is not the problem; the interests that have captured it are.

A title like Lawless: How the Supreme Court Runs on Conservative Grievance, Fringe Theories, and Bad Vibes is arresting, and there’s clearly a large audience hungry for explanation. Podcasts about “how much the Supreme Court sucks” are cathartic. But frames like these also foster an absurdist detachment—making us feel clever for spotting the con, while subtly reinforcing the idea that nothing can be done about it. When the Court is a meme, punchline, or doomscroll companion, it creates the political equivalent of nitrous oxide. We giggle at the latest doctrinal pretzel, then wake up without remembering the surgery. The joke becomes a mood and the mood becomes a posture: there’s nothing to do but laugh. That posture is not harmless; it’s another form of obedience in advance.

This posture also helps push offstage the reporting that identifies the funders, the pipeline, and the plan—Lisa Graves’s Without Precedent and David Daley’s Antidemocratic, among others. That displacement keeps the camera fixed on the shadows—the justices’ theatrics, their absurd arguments, their “bad vibes”—and away from the shadowcasters: the interests whose power the Court exists to protect.

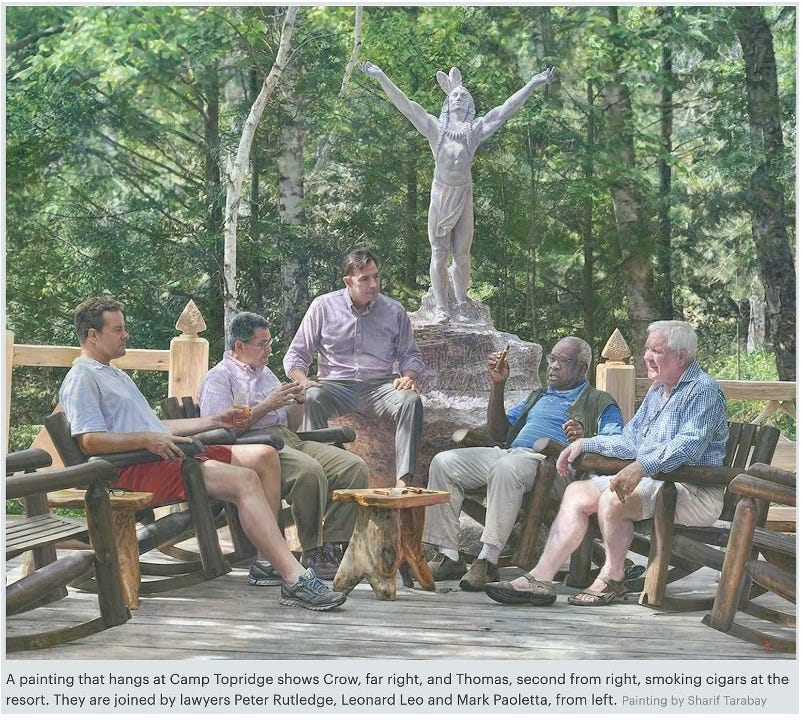

And remember: the legal commentators, former prosecutors, and scholars with the biggest platforms are not ignorant of that reporting—they are choosing to ignore it. They keep churning out “expert” analysis that airbrushes out everything we know about the Federalist Society’s decades-long project. The major news outlets covering the Court do the same. The unspoken rule is that since justices are presumed to be guided only by texts, doctrines, and interpretive theories, any suggestion that they are moved by the interests of their patrons—or by the elite social world they inhabit—is treated as taboo. It’s the etiquette of judicial mysticism: talk about law, never about power.17

Even those who are avowedly partisan have internalized the legal establishment’s manners. Consider this Substack title in my inbox over the weekend about Callais: “Is the Supreme Court About to Hand the House to the Republicans?” The title and post make clear that such a result would be disastrous for Democrats and for democracy—but they frame it as if the Roberts Court’s impending demolition of the Voting Rights Act were a natural disaster, not a political act. The Court’s work is treated like a Category 4 hurricane: something to track, to brace for, to survive—not to resist. And this is from a Substack whose mission is to make sense of the moment and advise Democrats how to talk about it.

The Limits of Tyrants

James Baldwin famously said, “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” If/when the Roberts Court kills the Voting Rights Act in Callais, it won’t be due to poor legal reasoning, Roberts’s principled opposition to considerations of race, nor even the advancement of the Republican cause. It will be due to the institutional mobilization of white Christian nationalism—the movement that has never relinquished its conviction that “real Americans” can only look like them. It is not a theory of law but a campaign of restoration, enforced through robes instead of rifles. So as you look to those who claim to guide you through this state of exception, ask yourself: are they preparing you to confront what must be changed—or training you to accept it?

The way out starts with clarity. Stop conferring symmetry where there is none. Stop calling capture “jurisprudence.” Stop laundering tyranny as “the Supreme Court decisions.” Name shadowcasters, not the shadows. Then act as if the government belongs to the people who live under it—because if we don’t, it never will. Abraham Lincoln made that clear with respect to the Taney Court “deciding” the slave question (Dred Scott) when he declared that

If the policy of the Government upon vital questions affecting the whole people is to be irrevocably fixed by the decisions of the Supreme Court... the people will have ceased to be their own rulers.

Frederick Douglass’s remarks in the wake of the Dred Scott decision remain fresh today in the wake of twenty years of the Roberts Court:

Power concedes nothing without a demand. Find out just what any people will quietly submit to and you have found out the exact measure of injustice and wrong which will be imposed upon them, and these will continue till they are resisted …. The limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress.

So, again, as you look to those who claim to guide you through this state of exception, ask yourself, are they preparing you for struggle or to simply endure?

Weekend Reading is edited by Emily Crockett, with research assistance by Andrea Evans.

ENDNOTE: Examples of headlines that attribute Callais to the “Supreme Court” rather than the Republican or Roberts Court:

The Supreme Court Case That Could Hand the House to Republicans (NYT);

The 2026 Election Is Being Decided at the Supreme Court (The American Prospect);

Playbook: How the Supreme Court could upend the midterms - POLITICO,

Is the Supreme Court going to doom the Dems? We did the math (The Argument),

Supreme Court likely to further diminish — but not end — Voting Rights Act cases (Law Dork),

Supreme Court reopens debate on key part of Voting Rights Act (Washington Post),

Supreme Court seems poised to further undercut the Voting Rights Act : NPR,

The Supreme Court Left No Doubt: It Will Gut the Voting Rights Act | The Nation,

How the Supreme Court taught Trump to rewrite history (Public Notice),

US supreme court appears poised to weaken key pillar of Voting Rights Act (The Guardian), A

Supreme Court ruling on voting rights could boost Republicans’ redistricting efforts (NPR),

Democrats Have One Brutal Path to Survival if the Supreme Court Kills the Voting Rights Act (Slate),

The US supreme court appears ready to nullify the Voting Rights Act | The Guardian

ENDNOTE: Why You Can’t Both-Sides the Justices

There are two major problems with characterizing the justices as “Republican” or “Democratic” based on the party of the president appointing them. The first is that the justices appointed by Democratic presidents haven’t consistently advanced Democratic positions on the bench. The second is that justices appointed by Republican presidents have consistently sided with the interest groups who advanced their nominations when those interests conflict with the short term interests of the Republican Party.

“Democratic” Justices Don’t Act Like Partisans

One analyst, in a long essay explaining why he would be using partisan rather than ideological labels, wrote:

Nor have Democrats failed to police their own nominees’ ideological conformity. None of the Supreme Court justices appointed by presidents Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, or Joe Biden broke with the Democratic Party’s approach to judging in the same way that Souter broke from the GOP’s. All of them generally supported abortion rights, affirmative action, marriage equality, and the Affordable Care Act. Every Democrat on the Supreme Court opposed Donald Trump’s claim that he could commit crimes while he was in office. All of the Court’s Democrats oppose the Republican justices’ decisions giving themselves a veto power over any regulatory decision made by the executive branch.

This forced symmetry pretends that justices nominated by Democratic presidents have approached rulings in the same way that those appointed by Republican presidents since Thomas have and that Democrats have approached Court nominations in the same way as Republicans have.

This is ludicrous. In case after case, Jackson, Kagan, and Sotomayor are defending long-settled doctrine—precedents largely authored or sustained by pre–Federalist Society Republican majorities—rather than pushing any “Democratic” program. And especially with respect to presidential immunity and the major questions doctrine, the three “Democratic Justices” were agreeing with respected Republican legal scholars and judges, including noted Federalist Society judge Michael Luttig. (Stevens and Souter dissented in Bush v. Gore; Souter’s draft dissent in Citizens United was so searing that Roberts reset the calendar to issue the opinion after Souter retired.) The both-sides frame is a sedative. It trains audiences to accept capture as business as usual.

Moreover, it is not uncommon — especially in areas like property rights, administrative limits, religious accommodation, or policing — for Democratic nominees on the Court to take positions that conflict with what Democratic activists or legislators would prefer. They often do so when issues involve institutional legitimacy, precedent stability, or legal doctrine constraints.

And, for a mic drop on this point, in 2014, Breyer, writing for a unanimous court (including Ginsburg, Sotomayor and Kagan) sided with the US Chamber of Commerce against allowing Obama to make recess appointments to the NLRB. This was a fully-briefed decision the National Review hailed as “brush[ing] back Obama’s unprecedented stretching of executive authority to appoint lower officials without the Senate … The whole affair puts on display President Obama’s abuse of presidential power.” Yet the Roberts Court unilaterally allowed Trump to fire the statutorily protected NLRB Commissioner Grace Wilcox without cause on the shadow docket.

Finally, while justices appointed by Republican presidents have timed their retirements to enable Republican presidents to name their replacements (O’Connor, Kennedy), Ruth Bader Ginsburg very consequentially did not. Those strategic retirements, along with luck, has meant that over the last 33 years, the Supreme Court has had a Republican majority despite occupying the White House for barely a third of those years.

“Republican” Justices Put Interest Groups Over Party

The six “Republican” justices are not partisan hacks, but agents of the coalition who captured the Court. The most compelling proof is the difference between the way the Roberts Court ruled in 2020 when it expeditiously rejected Trump’s election challenges and the way it ruled on his behalf in 2024, consistently overruling lower courts and strategically delaying the timing of its rulings. The difference: in 2020, business interests in the Federalist Society coalition were solidly against Trump remaining in office; in 2024 they were solidly in favor of his return to office. For more on this, read “Politicians in Robes: Part III.”

With respect to nominations, two illustrations of this point. First, George W. Bush had to withdraw his nomination of Harriet Miers because she wasn’t considered loyal enough by the Federalist Society, embarrassing a Republican president. Second, in the 2016 campaign, Trump committed to picking his Supreme Court nominations from a list developed by Leonard Leo, and as president he delegated judicial nominations to Don McGahn, who advanced Federalist Society candidates.

Nor Are They “Conservative” Justices

The Federalist Society justices are not “conservative.” As I’ve explained, their rulings do not adhere to any consistent legal principle, much less a “conservative” one. They are enablers of plutocracy and theocracy, ready to twist the Constitution beyond recognition for their desired outcome. They readily ignore conservative principles whenever it’s necessary to do so to realize their substantive aims. Similarly, their commitment to “originalism” has never been anything more than a post-hoc rationalization for rulings that have no other plausible explanation.

In case there’s confusion, in every other instance, we are talking about the Roberts Court. Bush v. Gore was decided by the Rehnquist Court, but in what very much foreshadowed the Roberts rule by law, the engine behind it was Antonin Scalia, one of the founding forces behind the Federalist Society project. It could also be argued that Gore’s gracious acceptance of that verdict, which led most other Democratic Party leaders to do the same, served as a proof of concept for Roberts as he executed similar ipse dixit maneuvers. In addition, Clarence Thomas—who was aided in his confirmation bid by Leonard Leo, who would go on to lead the Federalist Society—should have never been allowed to provide the fifth vote for Bush v. Gore, because his wife was screening people for key roles in the Bush administration.

For more on their roles, see Graves, Without Precedent, and Toobin, Too Close to Call.

Their roles in Republican administrations:

Clarence Thomas: Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights, U.S. Department of Education (1981–1982); Chairman, U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) (1982–1990)

Samuel Alito: Assistant to the Solicitor General (1981–1985); Deputy Assistant Attorney General, Office of Legal Counsel (1985–1987); U.S. Attorney for the District of New Jersey (1987–1990)

John Roberts: Special Assistant to the Attorney General (1981–1982); Associate Counsel to the President (1982–1986; Principal Deputy Solicitor General (1989–1993)

Neil Gorsuch: Principal Deputy Associate Attorney General, U.S. Department of Justice

Brett Kavanaugh: Attorney, Office of the Solicitor General (1989–1990); Associate Counsel in the Office of Independent Counsel (Kenneth Starr) (1994–1998); Associate Counsel to the President (2001–2003); Assistant to the President and Staff Secretary (2003–2006)

See, for example, Jeffrey Toobin, “Brett Kavanaugh’s Path to the Supreme Court Runs Through the Starr Investigation,” The New Yorker, July 10, 2018; Paul Blumenthal, “All The Lies Brett Kavanaugh Told,” HuffPost October 1, 2018; and David Lurie, “How Kavanaugh Likely Violated DOJ Policies While Working for Ken Starr” September 23, 2018, Slate Magazine.

The role of the Federalist Society has been well documented in deeply researched works beginning over a decade ago, including:

The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement by Steven Teles (2008)

Without Precedent by Lisa Graves (2025)

Captured and The Scheme by Senator Sheldon Whitehouse

Antidemocratic by David Daley (2024)

Dark Money by Jane Mayer (2016)

Shadow Network: Media, Money, and the Secret Hub of the Radical Right, by Anne Nelson (2019) — covers the Federalist Society’s connections within a broader conservative ecosystem

Ideas with Consequences: The Federalist Society and the Conservative Counterrevolution, by Amanda Hollis-Brusky (2015)

The Federalist Society: How Conservatives Took the Law Back from Liberals, by Michael Avery and Danielle McLaughlin (2013)

Networked Justice: The Making of the Conservative Legal Movement, by Amanda Hollis-Brusky and Joshua C. Wilson (2021)

From 1953 until President George W. Bush ended the practice in 2001, the American Bar Association had vetted federal judicial nominees—a nearly fifty-year bipartisan tradition of pre-nomination review. After that, President Obama briefly restored the process, but under Trump 1.0, the DOJ stopped requiring nominees to respond to the ABA questionnaire or provide access to bar and disciplinary records, and in 2025, the Department of Justice moved to further curtail the ABA’s role: cutting off advance notice, questionnaire participation, and access to disciplinary records. The ABA has warned that these changes will reduce transparency and weaken the vetting process.

For example, in the last term of the Rehnquist court the majority justices had an average of 77% approval votes from Democratic senators in their initial confirmation votes, with the lone justice not earning a “Yea” from the majority of Democrats being Clarence Thomas (he received just 19%). The majority justices on the current Roberts court have an average confirmation approval from Democrats of just 15%. A court with this low of approval from the opposing party is a historical anomaly, and there has never been a court majority - be it Democrat or Republican - composed of justices lacking support from the majority of the opposition party. Even as recently as 2016, the justices in the majority had an average of 56% percent approval from Democratic senators, and the justices in the last Democratic majority (on the Warren Court) had an average approval from Republican Senators of 80%.

ENDNOTE: Hijacking the Selection Process

There was no doubt that Democratic and Republican presidents preferred nominating justices who were generally more liberal or conservative, respectively. But that was in the context of the Court being an essentially conservative institution, in the sense that it was mindful of stare decisis and had a high bar for making dramatic or disruptive change. Even Richard Nixon, as John Dean details (with the benefit of extensive White House tapes) in The Rehnquist Choice, had a prosaic set of criteria when he nominated Rehnquist to replace John Marshall Harlan II. Those factors included electoral politics (which demographic voter block to appeal to), congressional relations (whom key allies favored), ease of confirmation, and generally being conservative.

And the relationship between outside interests and the judiciary was also quite different. Reread the Powell Memo now, and you are sure to find its ambitions quaintly modest by today’s standards. Its core argument was that business was not spending enough to make a better case to the judiciary, not that it should take over the judiciary.

But that all changed in 1987, when President Reagan nominated Robert Bork to the Supreme Court, immediately setting off a firestorm of criticism. Republicans have claimed that the backlash broke the norm of deference to presidents’ nominations. But in a way that echoes to this day, it is more accurate to say that the Bork nomination itself was the norm breaker. To this point, it was accepted that Democratic presidents would nominate those with liberal leanings, and Republican presidents would nominate those with conservative leanings – but that neither would appoint justices who intended to use the Court to revisit and change existing law, let alone legislate from the bench along rigid partisan lines. Bork very flamboyantly broke that mold. The defeat of the Bork nomination served to more or less preserve that norm for another two decades.

It wouldn’t be until the George W. Bush Administration that Republicans would formally ignore American Bar Association evaluations. By that time, the blessing of the Federalist Society’s Leonard Leo had become a prerequisite for successful nomination. A key turning point was when Leo quietly helped sink Bush’s nomination of Harriet Miers for being insufficiently committed to the Federalist Society agenda. Bush would not make that mistake again, as his next nominee, Samuel Alito, more than met that standard. Having cut his teeth as a strenuous advocate of rolling back voting rights in Edwin Meese’s Federalist Society-dominated Reagan Justice Department and assisting the Bush v. Gore legal team, Roberts was tapped early in his career for the combination of his intelligence, discretion, and devotion to the plutocratic agenda.

Of course, that accepts the limits to voting at the time – in other words, putting aside the larger question of the democratic legitimacy of Supreme Courts constituted before the 19th Amendment and the Voting Rights Act.

Roberts, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh and Barrett. Some don’t count Roberts or Alito this way because they were nominated in Bush’s second term after he did win the popular vote in 2004. Others argue that he would not have won in 2004 had he not been the incumbent.

Thomas was confirmed when Democrats were in the majority, something for which Joe Biden bears significant responsibility.

This is known as “judicial supremacy” in contrast to “popular constitutionalism, which I elaborate on in “The Courts Will Not Save Us,” and are further developed in Larry Kramer’s The People Themselves and The Anti-Oligarchy Constitution by Joseph Fishkin and William Forbath

ENDNOTE: Brown, the Civil Rights Movement, and the Voting Rights Act

After World War II, the Court seemed to do what politics could not: break the South’s veto over civil rights that had paralyzed Congress for half a century. Brown became the founding myth of modern liberal legalism—the story of nine wise justices, and courageous, whip smart lawyers, stepping in where congressional democracy had failed. It seemed that we could take for granted an institution whose new guiding light could be found in the footnote to Caroline Products. And, in fairness, Southern congressional intransigence made appealing the idea that, despite its actual record for the previous 150 years, the Supreme Court could stand against the injustices of the majority. But that romantic origin story overlooks Brown II, which, with its infamous instruction to desegregate “with all deliberate speed,” ensured that Brown would have little practical consequence (other than, perhaps, generating ferocious backlash).

The origin myth is also incomplete and outdated in that, especially over time, liberals came to believe that racial justice alone motivated Brown. In fact, national security considerations were crucial, and there’s a strong argument that Brown attenuated the possibilities of the civil rights movement. In Cold War Civil Rights, Mary Dudziak writes:

… the Cold War would frame and thereby limit the nation’s civil rights commitment. The primacy of anticommunism in postwar American politics and culture left a very narrow space for criticism of the status quo. By silencing certain voices and by promoting a particular vision of racial justice, the Cold War led to a narrowing of acceptable civil rights discourse … to the extent that the nation’s commitment to social justice was motivated by a need to respond to foreign critics, civil rights reforms that made the nation look good might be sufficient … the federal government engaged in a sustained effort to tell a particular story about race and American democracy: a story of progress, a story of the triumph of good over evil, a story of U.S. moral superiority. The lesson of this story was always that American democracy was a form of government that made the achievement of social justice possible, and that democratic change, however slow and gradual, was superior to dictatorial imposition. The story of race in America, used to compare democracy and communism, became an important Cold War narrative.

To be clear, there have certainly been protests against the Supreme Court around particular issues, especially abortion rights. My point is that there haven’t been protests against the Roberts Court’s seizure of democratic power.

For more on the role played by their social milieu, see The Company they Keep by Neal Devins and Lawrence Baum.

Another brilliant and vital contribution.

With love and deepest gratitude for your voice and your passion.

This article is an outstanding service and, yes, call to arms. Deep gratitude.