About that Times Poll

Separating the signal from the noise

I was swamped Sunday morning with reactions to the latest NYT/Siena survey (which I will refer to as “the survey” for the rest of this post) showing Trump leading Harris 48 to 47 percent among likely voters (including leaners, with a 2-point margin for Trump using unrounded vote shares). And now, with some serendipity as I go to publish, Pew has released its survey, which was fielded at about the same time, and which shows a dead even race among registered voters – placing it roughly midway between the Times’ result and the polling aggregates.

First of all, as I warned in “Beware of Mad Poll Disease In Good Times and In Bad,” and in “Mad Poll Disease Redux, Harris-Walz Edition,” it’s as dangerous to take too much encouragement from good polls as it is to be too discouraged by bad polls. It’s also dangerous to pay too much attention to national polls – not only because the Electoral College decides the outcome, but because there is much more local variation between the battlegrounds and the rest of the country than is ever acknowledged in media reporting.

And Nate Cohn offers this graphic which also makes the Mad Poll Disease point, which is that polling can’t tell us what we want it to. Focus on the bottom three bars. The top bar assumes that current polling averages perfectly anticipate which candidate will win - Harris by 46. But if the polls are off in the way they were in 2020, it’s Trump by 86 (third bar). However, if the polls are off in the way they were in 2022, it’s Harris by 68.

Nonetheless, it’s foolish to ignore the polls altogether when they send strong signals about what has to happen for either Harris or Trump to succeed. With the election so close, and with so much “news” about how this or that category of voters is trending this way or that, in today’s post I want to offer a more useful way to process that information, as well as take advantage of the cross-tabs and detailed methodology that the New York Times routinely publishes.

In short, the information we most need to process isn’t the topline result of whether Harris is up by 1 or down by 2. It’s the clues we can find elsewhere in the survey about whether our number-one job – making sure voters understand the stakes of the election by October – is on pace or not. Right now, that essential work seems to have stalled, but there is still time to rev it back up – especially with the groups among whom Harris’ margin is trailing Biden’s margins in 2020, like younger voters1and Latino voters.

Historical Context

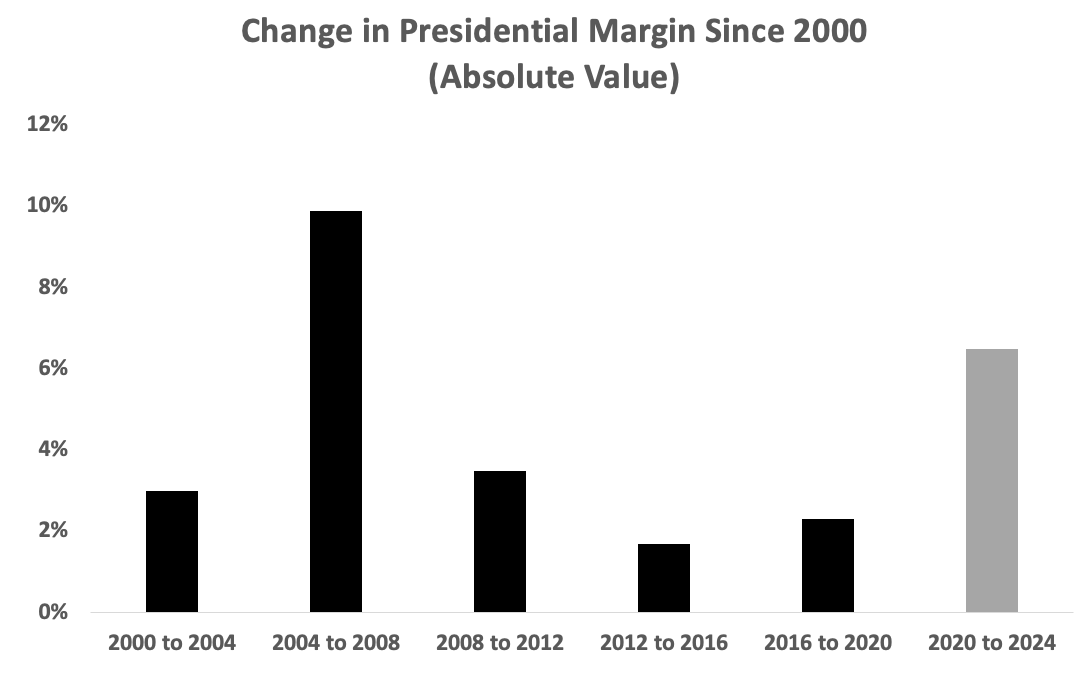

First, it’s worth putting a Trump 2-point national margin in context. The next graph shows how much the Democratic margin2 changed from one presidential cycle to the next, in absolute values to show the magnitude of the swings in the 21st Century, with the new survey results in gray.3 In other words, other than the post-crash 2008 swing to Obama, the 6.5 point swing between 2020 and 2024 indicated by NYT/Siena would be the largest of the century by a factor of two or more. On the one hand, we (properly) hear about how ossified our politics have become and how rarely people change their minds; on the other hand, this survey suggests a tectonic shift underway as large as 2008, when voters were overwhelmingly rejecting an administration for its forever wars, the Great Recession, Katrina, etc. How likely do you think that is?

Again, my argument is not that we should simply ignore the poll, but to make two points. The first is one I’ve repeated often – when polls show big swings like this, the responsible thing to do is to look for some real world corroboration. At about this point in 2020, both the NYT and Post/ABC headlined double digit leads for Biden in Wisconsin, a state that he ended up winning by only 20,000 votes after Clinton lost it by 20,000 votes four years earlier. Anyone with a basic understanding of Wisconsin state politics, where the electorate is famously evenly divided by partisanship, should have been severely skeptical of those polls.

My second point is that when the results are dramatic or surprising – the sensible reaction is to understand the sources of whatever changes they show. This post will offer a guide for how to do that. I emphatically am not trying to rationalize away your anxiety by unskewing the poll or some such thing; rather, I’m surfacing what about it is worth paying attention to (and what isn’t).

Contemporary Polling Context

It’s worth noting the ways in which these survey results differ from what others are seeing in their polling. First, and most obviously, Trump being up by 2 is 4 points off the Times’ own polling average, which has Harris up by 2. Much more puzzling is that according to FiveThirtyEight, the current net favorability for Trump is -9.7 points and -0.3 points for Harris (a 9.5 point spread in Harris’ favor), while Times/Siena has Trump favorability at only -6 points and Harris’s at -5 points (only one point in Harris’s favor).

Big-Picture Context (What Every Poll Misses)

Polls can tell us what voters tell pollsters they care about, in response to forced-choice questions that may or may not represent what occupies those voters’ minds on a daily basis. But polls cannot tell us what will determine whether an infrequent voter casts a ballot or stays home. There’s a huge difference between a voter saying which candidate is better in a forced choice, and a voter believing that whomever is “better” is better enough to turn out and vote for.

Let’s take two infrequent or contingent voters, who I’ll call Tom and Susan. Tom says his top issue is “inflation/prices,” and Susan says “abortion.” Neither has a favorable view of either candidate, and neither is sure if they will vote this year. Thus, it’s pretty likely that even though inflation/prices is Tom’s top issue – and even if he said “Trump” when asked in another question who he thought was better on the inflation/prices issue – that’s different from him believing that Trump would actually solve inflation/prices, or believing it strongly enough to bother turning out to vote for Trump. On the other hand, whatever else Susan may think about both candidates, if she hasn’t decided yet, and if her most most important issue is abortion, whether she votes is very likely to depend on whether she believes that Trump would enact a national abortion ban (if she’s pro-choice) or how much she believes Harris would codify Roe (if she’s not).

Why is abortion more likely to drive Susan to vote than prices to drive Tom? One of the most solid findings in behavioral science is the power of loss aversion on human beings. By loss aversion, I mean that most of us are wired to be more likely to act to avoid loss (such as losing a fundamental right) than we are to act in pursuit of gains (such as possibly seeing a lower grocery bill). That’s why awareness of the consequences of the MAGA governing agenda has been the driver of the highest sustained turnout rates in the modern era over the last three cycles. This surge of new and infrequent voters has been consistently anti-MAGA by large margins. But they only show up if the MAGA stakes are clear.

Pinpointing the Sources of Harris’ Polling Decline

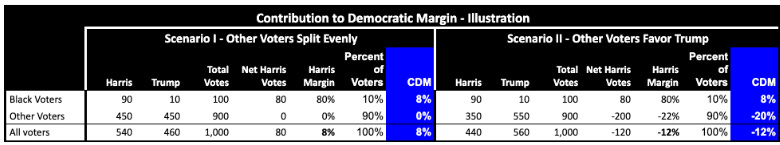

In order to properly allocate the sources of apparent shifts in Democratic support since 2020, we need a better metric than the horse race numbers alone for individual segments of the electorate. We need to be able to account for the relative sizes of different groups in the electorate. In order to do that, we need a simple but powerful metric I created called Contribution to Democratic Margin (CDM).

Contribution to Democratic Margin (CDM): Telling the Whole Story About Voter Blocs

Most news coverage of polls will report, and attribute great significance to, the ups and downs in the horse race for particular demographic groups (e.g. young voters of color, white non-college voters). But such narratives never put in context how important these polling shifts might be to the final result. For example, we might hear that Democrats are doing 10 points worse with Latino voters – but we are never told (and I’m confident none but the most informed practitioners could readily tell) how much that affects the bottom line of winning the election. In terms of the bottom line, that 10 point swing in Latino support is the equivalent of about a 2 point shift in the preferences of college voters. In other words, we are only told half the story. (At best.4)

For the whole story, we need Contribution to Democratic Margin (CDM), which tells us the extent to which a given group helps Democrats win or lose. CDM is simply the Democratic margin for a particular group, multiplied by that group’s share of the electorate. It really is that simple.

For example, if Black voters support Harris 90 percent to 10 percent, the Democratic margin is 80 points (90-10). If Black voters make up 10 percent of the electorate, then the Contribution to Democratic Margin is 8 points (80 points times 10 percent). In other words, if Harris broke even with all other voters, she would win the popular vote by those 8 points, or 54-46 – no additional math required.

Vote History

Now, with the basics of CDM under our belt, let’s diagnose the sources of the NYT/Siena survey’s 6.5-point swing to Trump since 2020, starting with people who voted in 2020.

2020 Voters

The survey assumes that 83 percent of 2024 voters will consist of those who voted in 2020. If all of those returning voters stuck with their 2020 party, and turned out in equal proportions, then returning Biden voters would give Harris a bit more than 43 percent of the total vote and Trump a bit less than 40 percent of the vote. Or, to use our new metric, the CDM for Biden voters in 2024 would be 43 points, and for Trump voters -40 points.

But, in the survey, mostly because more Biden voters say they will vote for Trump (6 points) than Trump voters say they will vote for Harris (2 points), the CDM for returning Biden voters is only 37 points and for returning Trump voters is -38 points. In other words, where returning 2020 voters should give Harris a 3 point lead if they kept their vote choice constant, in the survey, they give Trump a 1 point lead. That explains 4 points of the swing from 2020 to 2024.

The survey does report 2020 recalled vote in an imperfect but useful way, which allows us to compare the survey banner points with the Catalist results for 2020. If the Catalist estimates are accurate, and if the recall is accurate, then the comparison should show us where that 4 point erosion I just described is coming from, again, using CDM. The three biggest sources of decline were men (-3) and rural (-4). At the same time, Harris makes somewhat offsetting gains with college graduates (+4).

Here, the just released Pew makes a very important contribution. Because they have been tracking validated voters since 2016, their breakdown of how Biden and Trump voters plan to vote now is based on how those voters said that they voted at the time, as opposed to most surveys, including the Time/Siena survey which relies on respondents’ recall of their 2020 vote. Some have argued that, in fact, current polls underestimate the extent of partisan side-switching as respondents may be recalling they voted for Biden or Trump to align with their current preferences.

This table compares the Times/Siena numbers for registered voters with Pew’s.5 As you can see they got identical results for 2020 Biden voters, and differ by 2 points on the percent of 2020 Trump voters who plan to vote for Harris. But, bottom line, recalled vote is still very accurate.

2020 Non-Voters

The other two points of Trump’s gain come from his 9-point lead in the survey among those who did not vote in 2020. Since those surveyed who did not vote in 2020 are very disproportionately younger voters, this strongly suggests that those younger voters who didn’t vote in 2020 actually favor Trump, putting them on the opposite side of the partisan divide from those in their generation who did vote in 2020.

Note in the table above that this is something in which there is significant difference between the Pew result for those voters - Harris +4 and NYT/Siena - Trump +8, a 12 point span. (If you are confused, remember that to compare NYT/Siena with Pew I had to switch to registered voters.)

But, here, again, we have a startling result that deserves further investigation before we take it at face value. It either represents a major defect in the survey, or a major social change in America (and a major problem to be addressed).

Favorability

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the discrepancy between this survey and the national aggregates is with respect to favorability ratings for Trump and Harris. As I already mentioned, while the FiveThirtyEight national aggregates give Harris a net advantage of about 10 points, this survey estimates it at just one point, with Trump less disfavored and Harris more disfavored in the survey than in the aggregates.

In June, before the debate, the Times/Siena survey showed Trump’s net favorability to be -8 and Biden was at -17. So, in those two months, Trump improved about 2 points, and Harris improved by about 10 points over where Biden had been. While FiveThirtyEight Trump net approval is lower than the Times, the trend over the same period also shows about a 2 point gain for Trump. (Note in passing - Harris’ disproportionate favorability gains have translated into only a 2 point improvement over Biden’s deficit in the horse race though.)

Between June and September, in the Times/Siena survey, Trump saw the greatest improvement in net favorability with Latino and young voters, while sliding with Black voters. Harris’ gains over Biden since June were positive across the board but were greatest with Black voters, suburban voters and voters under 44.

The importance of these demographic groups, and what these results tell us about what Harris needs to do to win, will become clearer in a moment.

The Big Mystery?

Part of the conventional understanding of the last few months has been dead on: Harris has done much to allay Democrats’ concerns about Biden. This has translated into big gains in net favorability – but, especially in this survey, much more meager gains in the horse race. What gives?

Trump is clearly rattled by the attention Harris is getting, and by his seeming inability to change that. But remember – through his years in office, as well as afterwards, it was generally the case that Trump’s net approval was negatively correlated with how much attention he was getting in the mainstream media. That is, the more people heard about him, the more they disapproved of him.

My argument since before the 2020 election has been that there is an anti-MAGA majority in America, but not necessarily a pro-Democratic majority. Again, the new and infrequent anti-MAGA voters Democrats need have, thus far, been driven primarily by loss aversion.

While the Harris-Walz “joy” is absolutely stoking base enthusiasm and yielding soaring fundraising numbers, it’s likely only half the strategy needed to win. Remember what Harris said at the convention:

Fellow Americans, this election is not only the most important of our lives, it is one of the most important in the life of our nation. In many ways, Donald Trump is an unserious man. But the consequences of putting Donald Trump back in the White House are extremely serious.

Joy, “weird,” happy warriors – all of that supports the first part about how “Donald Trump is an unserious man,” which brings the attitude of defiance and mockery that historically helps take down fascist regimes. But the other part – voters’ belief that “the consequences of putting Donald Trump back in the White House are extremely serious” – is what has actually driven anti-MAGA turnout over the last three cycles. That part of the equation is currently stalled.

The Times/Siena surveys give us a few ways to gauge what voters know – and more importantly, believe – about these consequences.

Trump Threat Consciousness

We often hear that Trump's negatives are already “baked in” with the electorate. It’s true that most voters have already made up their mind about Trump as a person—that he is either too detestable to vote for, or detestable but still worth voting for, or perfect in every way.

The same is not remotely true for people’s ideas about what Trump would do if elected. The more people understand what he will do and believe he will do it, the more likely they are to not just oppose him, but be motivated to turn out and vote against him. I'll call this understanding and belief “Trump threat consciousness.” Critically, Trump threat consciousness is not static. Many infrequent voters who would vehemently oppose Trump's agenda (e.g. nearly-unchecked presidential power, using the DOJ to punish his political enemies, detention camps, abortion bans) aren't yet paying enough attention to either associate Trump with that agenda, or believe he would carry it out.

Several questions in the NYT/Siena poll give us some insight into the current Trump threat consciousness of the electorate:

Found Trump Offensive Recently

The survey asks “Has Donald Trump ever said anything that you found offensive?” The offered responses are “yes, recently (43 percent),” “yes, but not recently (27 percent)” and “no (29 percent).” No surprise - nearly everyone who answered “no,” also favor him against Harris, which suggests that about 40 percent of those who favor him against Harris acknowledged finding him offensive at times.

“Not recently” answer is a good marker for voters who likely opposed him before, but are not paying attention now. Young voters, Latino voters, and non-college voters were disproportionately likely to say “yes, but not recently,” while college educated voters were much more likely to say “yes, recently.”

It’s truly astounding that a third of the electorate is apparently paying this little attention to Trump’s offensiveness, especially given how much more offensive, and unhinged, he has become in recent months.

Much “credit” for this has to go to the six Republican-appointed Supreme Court justices (including three appointed by Trump, and two compromised by their wives’ support for Trump’s insurrection) who went out of their way to make sure Trump would escape legal accountability for January 6th and many other crimes before the election. But for that act of judicial election interference, we would have seen months of news cycles focused on Trump’s bad deeds. Low Trump threat consciousness didn’t just fall out of a coconut tree; John Roberts is sitting up in the tree throwing coconuts at us.

How Risky

If voters aren’t hearing Trump say offensive things, are they hearing about how risky his plans are? Once again, the last time this question was asked was in April. Given what has come out since then about Project 2025, not to mention Trump’s escalating threats to have his political enemies rounded up, it should be astonishing that by about 5 points, Trump is seen today as a less risky choice (net) than he was in April.

Project 2025

Wait a minute! Didn’t this survey indicate, and haven’t other surveys indicated, a startling amount of awareness about Project 2025? Trump has tried to distance himself from this 900-page playbook, but we have every reason to believe it would inform his administration’s personnel and policy. The more voters learn about it, and believe that it reflects what Trump will do if he is elected, the more they oppose it and him.

It’s true that most people say they know something about Project 2025. But let’s take a closer look:

Knowing “a lot” about Project 2025. Those who say they know “a lot” about Project 2025 favor Harris by about 70 to 25 – but only 27 percent say they know “a lot” about project 2025.

Knowing “nothing at all” about Project 2025. Almost as many know nothing as know a lot, and this group favors Trump by about 67 to 27 points.

Noticeably, young voters, Latinos, and non-college voters are very much less likely than other groups to say they know “a lot” about Project 2025, and very much more likely to say they “know nothing at all.”

All of this gets to why media-survey-sample-sized surveys can’t tell us as much as they might seem to.

First, we don’t know whether respondents believe that the Project 2025 policies will be implemented if Trump is elected. This question seems to cover that: “Thinking about Project 2025, do you expect Donald Trump to try to enact most of the policies, just some of them, or do you think he will not try to enact any of the policies outlined in Project 2025?” But it falls short, because:

there’s a difference between believing Trump will “try to enact” the policies and believing that the policies really could be enacted, and

there’s no way of knowing whether the respondent is aware of whatever provision(s) would be most damaging to them when they say they know about Project 2025. In other words, they may have heard Project 2025 is a bad thing in an abstract way – but that’s different from believing, say, that their neighbor could be rounded up in mass deportations, or that their daughter could be affected by a national abortion ban.

A second limitation is that there are not enough interviews to suss out any of this at an operational level. Here’s an illustration. In a campaign context, you would want a banner point of voters who had supported in Biden in 2020 but are not supporting Harris now to get closer to understanding the extent to which that reluctance is based on not believing what a second Trump Administration would bring (as opposed to what they think of Harris, which I will turn to in a moment).

These two limitations invariably lead to a lot of smart-sounding but hand-wavy generalizations based on ecological fallacies. A quick illustration of that: usually when a “most important issue” moves up or down the ranking list, that’s taken at face value to be a causal factor in changes in the horse race. For instance, if “democracy” moves down the list in a poll where Trump improves over Harris, the immediate assumption would be that people are swinging to Trump because they care less about his threats to democracy.6 But, such swings are just as likely to reflect changed issue rankings among the 80-ish percent of voters who will never change their minds as it is for those who actually may. Even if you knew exactly who the “swing” group is, that’s only 300 or so interviews, and the MOE is too large to support firm conclusions.

Harris Consciousness

One of the most widely reported angles on the campaign since Harris became the Democratic nominee has been the race to define her. The survey asks whether “you feel like you still need to learn more about Kamala Harris, or do you pretty much already know what you need to know?” Overall, 28 percent of likely voters said they needed to know more.

Significantly, disproportionately more of the Democratic-leaning groups that are trailing their 2020 levels of Democratic support say they need to know more – including 18-29 years old (53 percent), Latinos (43 percent) and Blacks (41 percent).

Let’s return to the question about risk (see above for the chart on the same question about Trump). In April, voters saw Trump and Biden as equally risky (in Biden’s case, presumably because of his age). They now see Harris as 9 points less risky than they saw Biden in April – which is still only 4 points less risky than they currently see Trump. Again, joy has helped, but it’s only half the battle.

Conclusion: Takeaways

Harris has done an amazing job of consolidating and energizing the Democratic coalition. But anti-MAGA voters, those who hadn’t been regular voters before 2016 and still don’t have favorable views of Democrats but came out to vote against Trump in 2020 and Republicans in 2018 and 2022 still seem disengaged.

With that, I’ll leave you with the only numbers that should matter if you care about keeping Trump and MAGA out of power:

How many people will vote?7

142 million 2024 voters in a “low-turnout” election.

167 million 2024 voters in a “high-turnout” election.

Who will they be?

100 million voters who turned out in 2022.8

42 to 67 million others.

Out of what realistic pool will the 42 to 67 million others come?

65 million who have voted in at least one of the last four elections (but didn’t vote in 2022).

25 million voters who have newly registered since the last midterm.9

13 million young voters who registered for the first time in 2021 or 2022, but have never voted.

That’s a pool of 103 million people who have either voted before or who are recently eligible and registered. Two thirds of them have already voted for Clinton/Biden/House Democrat or Trump/House Republicans in the last four elections and most of those who would be voting for the first time have chosen sides already too. Whether more who support Harris than those who support Trump turn out will do more to determine who is taking oath of office in January 2025 than how many habitual voters can be persuaded to switch from one side to the other.

Weekend Reading is edited by Emily Crockett, with research assistance by Andrea Evans and Thomas Mande.

Throughout, I’ll use “younger voters” instead of the clunkier “voters 18-29.”

Reminder: the “margin” is the difference between the vote shares of the winner and the loser; a 55-45 D-R split would mean a 10-point Democratic margin (and minus-10 if the vote splits the other way).

I’m using absolute value for these purposes, because in terms of variability to express Obama’s drop from 7.4 in 2008 to 3.9 in 2012 as a 3.5 point “swing.”

Further complicating matters, these apparent “shifts” are often just statistical noise. In “Terrible Food, and Such Small Portions,” I explained the methodological issues that lead even high-quality pollsters to disagree about the demographic composition of the electorate.

For this one comparison I’m shifting from the Times/Siena cross tabs for likely voters to registered voters to conform with Pew, which only has registered voters.

These kinds of assumptions helped fuel off-base media narratives ahead of the 2022 midterms. Admirably, Nate Cohn recognized this and has made efforts to correct for it.

The lowest turnout rate in the last three presidential elections was 59 percent nationally; the highest was 69 percent, which is consistent with deriving a national number based on the lowest and highest turnout rates in each state over the last three elections.

Since 91 percent of previous midterm voters voted in both 2016 and 2020, I’m assuming 90 percent of 2022 voters will vote again in 2024.

Historically, 60 to 68 percent of new registrants vote in the next election they are eligible for.

These are observations I never see reflected in polls. I’m not a statistician or a psychologist, but why is Trump polling well enough for this year to be a horse race?

Fewer ppl show up to Trump’s rallies&those who show up frequently thin out before Trump’s done ranting.

Very few show up for Vance rallies vs Walz.

Trump looks terrible. It’s not just aging. He looks like he’s led a life of excess. He’s obese, saggy. The things Trump does to try to remedy his aging appearance, the fake tan, the frizzy over processed hair make things worse. Than there’s the gait, mispronouncing of words, forgotten names.

I don’t think the folks at Heritage give a shit if Trump knows what’s going on, but Trump’s appearance&behavior has to affect opinion of voters.

I know we are very tribal.

However, the overturning of Roe. The mistreatment of women in reproductive crisis, Trump’s coarse pronouncements of VP Harris past, disgust most women.

After 16, I will never say never, particularly with the outdated Electoral College, but Trump is now older, plainly has dementia&a known failed commodity.

I’m hoping those things are enough to propel Kamala Harris to the presidency

Came here from Sabato's. Thanks for the insightful piece.

I would be curious to know if 1) tightened poll margins in swing states are reflected in other states and 2) if that number tells us about the current state of polling.

Considering that 50% of the population lives in 9-10 states, wouldn't the margins in states like CA, NY, IL, etc. have to be much tighter and/or Margins in TX, FL, and OH much wider and/or margins in the 35 non-swing, small pop states decidedly more Trump-leaning than in 2020 in order to result in a tied national race?

Perhaps there's not enough polling or I'm missing something?